The Wisdom of Chris Hohn

A Deep Dive into the Principles of Outperforming the Market through Quality

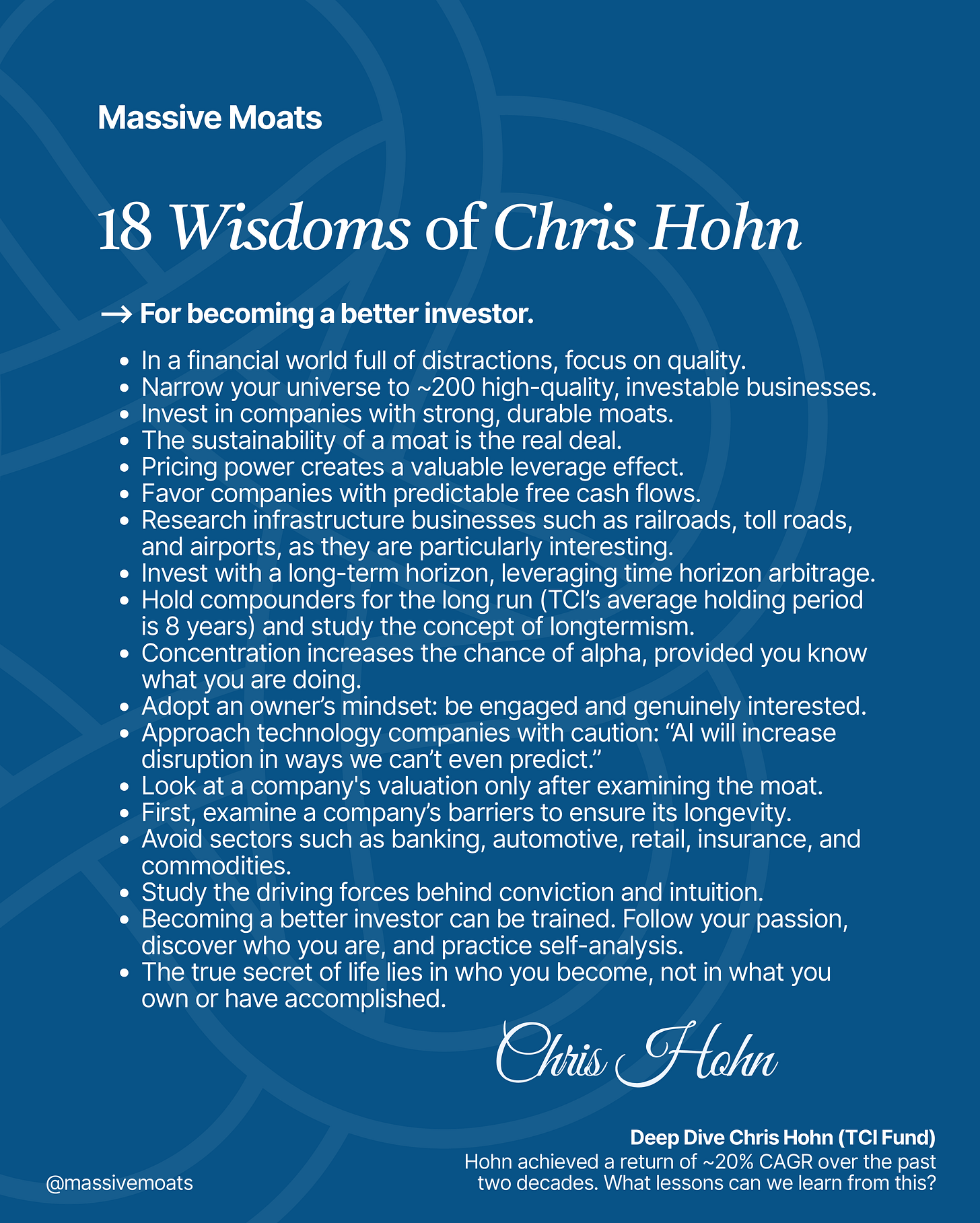

Chris Hohn (58) has consistently outperformed the benchmark, achieving a compound annual growth rate of ~20% since 2003 with his hedge fund, The Children’s Investment Fund (TCI). Hohn’s net worth is estimated at $11.5 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Beyond his personal wealth, Hohn has also created significant value for philanthropic purposes, including through his The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF).

This deep dive explores the underlying principles that have enabled Hohn to beat the market for over two decades. With his small investment team at TCI, Hohn focuses on selecting high-quality companies with strong moats. He notes that it took him years to fully understand what this qualitative approach truly entails.

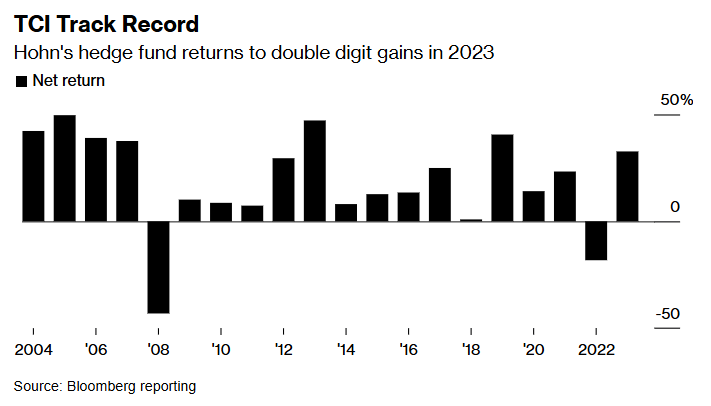

The success of TCI has not followed a linear path, however. In 2008, for example, the fund posted a return of -43% after pursuing radical change in underperforming companies. In the years that followed, several colleagues left TCI, prompting Hohn to refine his strategy and reallocate his focus to the qualitative realm of the financial world. This period of transition provides valuable insights for us as investors.

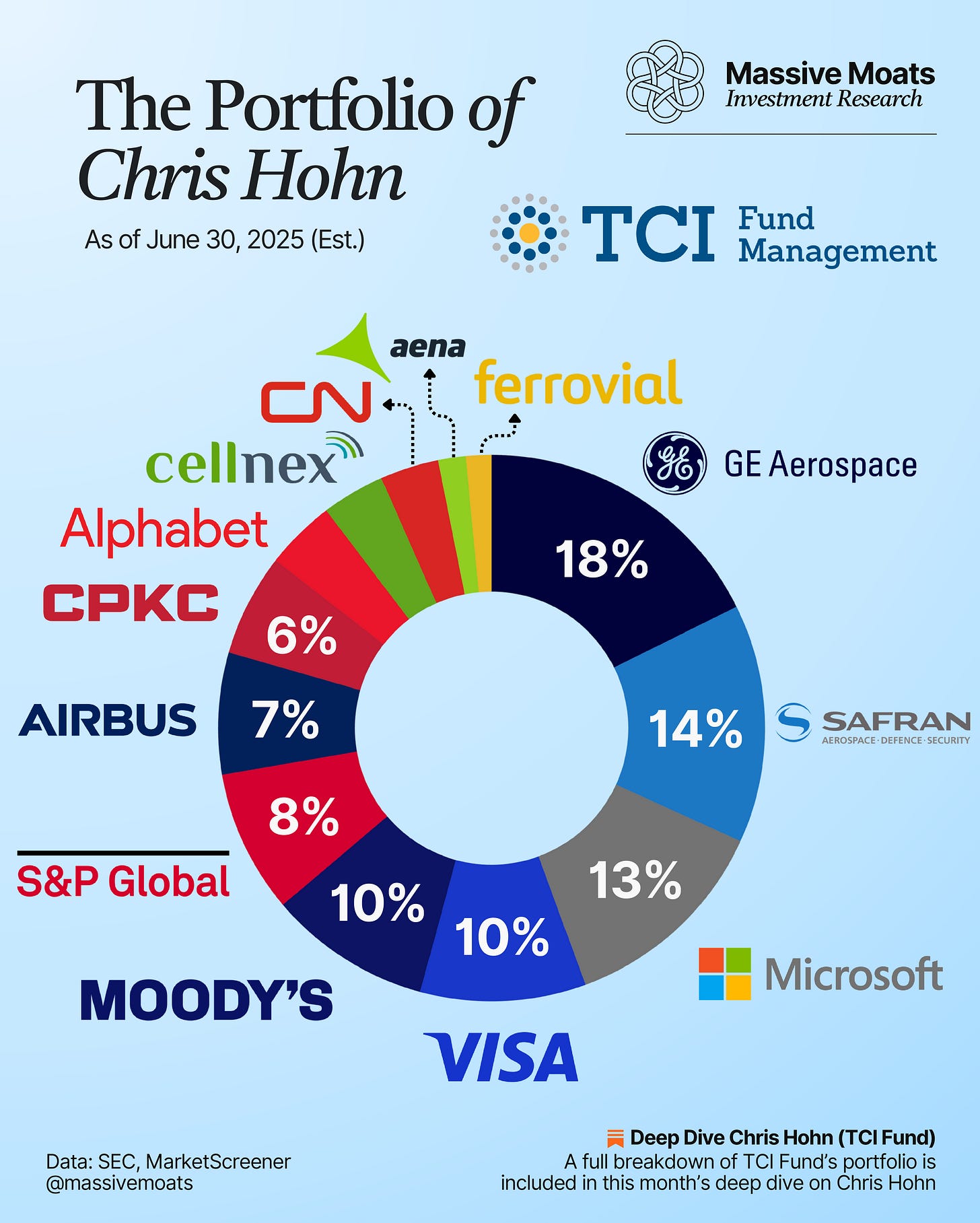

As of 2025, top positions in TCI’s portfolio include strong moat companies such as GE Aerospace, Safran, Microsoft, Visa, Moody’s, and S&P Global. According to Hohn, these belong to a select group of high-quality, investable companies. This deep dive examines the TCI portfolio alongside Hohn’s available commentary, supplemented by my own analysis of these companies.

What drives Hohn to select these particular companies? Which sectors does he favor, and which does he exclude upfront? And what is his view on technology companies and the ever-evolving forces of AI?

This deep dive addresses these questions and distills the many lessons Hohn has accumulated over the past decades.

I hope you find this deep dive insightful,

Eelze Pieters

September 21, 2025

Note

This deep dive does not constitute investment advice. Read the full disclaimer here.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1. Introduction

Chapter 2. Strategy

Chapter 3. Shareholder Activism

Chapter 4. Moats, “The Real Thing”

Chapter 5. Valuation

Chapter 6. Concentration & Sectors

Chapter 7. TCI’s Portfolio Breakdown

Chapter 8. Longtermism

Chapter 9. Conviction & Intuition

Chapter 10. Conclusion: What Makes a Good Investor?

Chapter 1. Introduction

Christopher Anthony Hohn (Chris Hohn) was born in October 1966 in Addlestone, Surrey, a village near London in the United Kingdom. Hohn’s father, an auto mechanic, emigrated from Jamaica to England in 1960 after marrying Hohn’s mother, a legal secretary from East Sussex (The Telegraph, 2008; Hohn, 2021; The Guardian, 2021).

This background would shape Hohn into a fiercely independent thinker: “It made me an independent thinker—growing up as an outsider and feeling different. It gave me a work ethic and a desire to achieve something” (Hohn, 2025).

While studying Accounting and Business Economics for his BSc at Southampton University, Hohn took an Entrepreneurship course taught by a visiting professor from Harvard Business School. This course laid the groundwork for Hohn’s future career path, as the professor encouraged him to apply to Harvard (2025). A few years later, Hohn was accepted into Harvard’s Master of Business Administration program, graduating in the top 5% of his class.

In my research into Hohn and his hedge fund, I discovered that beyond many of our shared investment principles, we also have a similar academic background. I completed a bachelor’s degree in Business Economics (Finance & Control) and a master’s in Business Administration, with a specialization in Organizational and Management Control. In this deep dive, I will also share my own insights along the way. While Hohn and I share many views, there are certain points where my perspective on specific companies and sectors differs from his. I hope you will find this dual-layered approach insightful.

After graduating from Harvard, Hohn began his career in 1994 at Apax Partners, a private equity firm, where he worked for several years. In 1996, Hohn moved to the United States to work on Wall Street at the hedge fund Perry Capital. He later established a European branch for Perry Capital in 1998. Hohn would remain with Perry Capital for seven years before founding his own hedge fund, The Children's Investment Fund (TCI), in 2003 (The Financial Times, 2012; Hohn, 2021).

TCI seeks to invest in high quality companies with sustainable competitive advantages. [...] Using a private equity approach, TCI conducts deep fundamental research, constructively engages with management and adopts a long-term investment horizon.

— The Children's Investment Fund (Source: TCI, 2025)

The Children's Investment Fund (TCI)

On June 5, 2003, Hohn signed the incorporation papers for his own hedge fund, and in January 2004, he launched TCI's Master Fund. The fund quickly attracted significant capital, including inflows from foundations and endowments, drawn by Hohn’s commitment to allocate one-third of TCI's management fees to The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), a charity established by Chris Hohn and his former wife, Jamie Cooper (a more detailed explanation of CIFF will follow later in this chapter).

Performance

Since its inception in June 2003, TCI has reportedly generated a return of between 18% and 20% CAGR (Hedge Fund Alpha, 2024; Yahoo Finance, 2024; NBIM, 2025). During the same period, the S&P 500 Index delivered a return of approximately 10% CAGR, including reinvested dividends (Clark, 2025). This translates to an outperformance of roughly 9 percentage points CAGR over a 21-year period for TCI (NBIM, 2025).

Below provides an overview of TCI's reported and estimated returns for the most recent years, benchmarked against the S&P 500:

2018: 0.9% (vs. -4.4% for S&P 500) (Bloomberg, 2020);

2019: 41% (vs. 31.5% for S&P 500) (Bloomberg, 2020);

2020: 14% (vs. 18.4% for S&P 500) (Bloomberg, 2021);

2021: 23.3% (vs. 28.7% for S&P 500) (Institutional Investor, 2022);

2022: -18% (vs. -18% for S&P 500) (Bloomberg, 2024);

2023: 33% (vs. 26% for S&P 500) (Bloomberg, 2024);

2024: 15% (vs. 25% for S&P 500) (Institutional Investor, 2025);

H1 2025: 21% (vs. 6% for S&P 500) (The Financial Times, 2025).

The chart below shows TCI’s annual returns since the fund's inception, with negative returns only recorded in 2008 and 2022.

Transformation

TCI has not been without its challenges. For instance, in 2008, the fund posted a return of -43%, compared to a -37% return for the S&P 500. In the wake of these negative results, it was announced in January 2009 that Patrick Degorce, a founding member of TCI, had left the fund (Reuters, 2009; The Wall Street Journal, 2009). Other “star analysts” also departed TCI in the period that followed (The Financial Times, 2010; 2012). Additionally, capital began to flow out as investors who had completed their 3- or 5-year lock-up periods decided to redeem their assets (Institutional Investor, 2022).

Patrick Degorce subsequently launched his own hedge fund, Thélème Partners, attracting several other former TCI colleagues. In 2010, Thélème Partners raised £446 million (The Financial Times, 2010).

In the year following the -43% loss, 2009, TCI achieved a return of 10%, while the S&P 500 gained 26%. TCI also underperformed in 2010 with a 9% return, as the S&P 500 increased by 15%. Hohn realized he had to reinvent TCI.

We had strayed from being heavily invested in stocks, with a high barrier to entry and a bulletproof franchise to weaker industries. Then we weren’t fully invested in 2009. The team and the fund got too large.

— Chris Hohn (Source: Institutional Investor, 2015)

In the years that followed, Hohn moved away from special situations and value strategies focused on distressed companies and those with strong commodity characteristics. He shifted his attention back to strong businesses: monopolies with wide moats, high barriers to entry, and significant pricing power (Institutional Investor, 2022).

TCI Investment Team

Hohn achieved his approximately 9 percentage-point CAGR outperformance over the past 21 years with his investment team, that now counts 7 to 8 colleagues, in addition to a back office, according to Hohn (2025). The investment team has shrunk over the years; in 2008, Institutional Investor (2008) reported that TCI Investment Fund Management had 16 investment professionals.

After Hohn and his team rediscovered their focus, the fund’s performance also improved. Hohn attributes TCI’s current success, in part, to its culture and the “intangible trust” that exists within the firm.

It’s small—very small—it’s collegiate. We’ve known each other a long time and there’s something that we’ve built, which is an intangible trust.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

According to Hohn, his best people would not stay if TCI’s investment team were to grow to one hundred members, as he believes it would become too impersonal.

Hohn asserts that the best employees don’t work for the money; they work for a great environment, proper conduct, and, above all, a shared purpose. A new colleague must therefore share the same philosophy as TCI. Hohn describes his colleagues as team players who are pragmatic and open-minded, in addition to having expertise within the financial realm and a shared investment strategy. According to Hohn (2025), this is tested with one or more case studies during the application process.

The foundations of TCI's success will be detailed further in this deep dive. Below is a brief look at CIFF.

The Children's Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF)

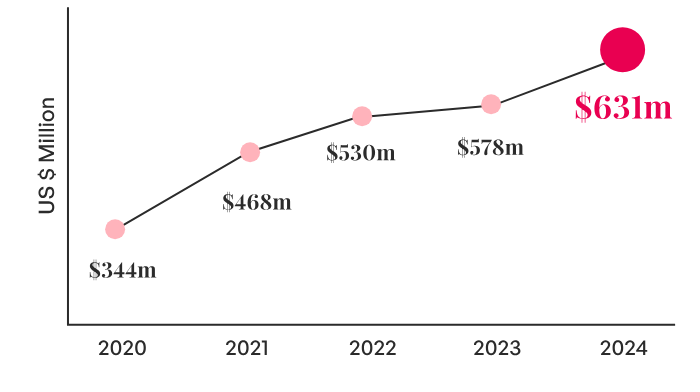

With offices in Addis Ababa, Beijing, London, Nairobi, and New Delhi, The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) collaborates with numerous partners to improve the lives of children and young adults (CIFF, 2025).

In a world where wealth and influence can shape outcomes, those with significant resources must consider how to use philanthropy to drive meaningful and lasting change.

— Chris Hohn (Source: Annual Report 2024 CIFF, 2025)

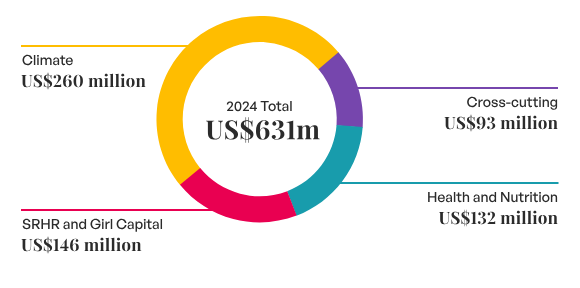

CIFF manages an endowment of $6.1 billion. In 2024, it committed $923 million to programs, of which $328 million were additional donations from Hohn himself (CIFF, 2025).

The foundation's funds are primarily used for two key initiatives: climate change and child health in Africa and India.

Structure

The original structure stipulated that TCI would donate one-third of its 1.5% management fee to CIFF, plus an additional 0.5% of assets for any year the fund achieved a return of 11% or higher (The Telegraph, 2008). This arrangement changed after the divorce between Hohn and his former wife, Jamie Cooper, resulting in donations being made on a discretionary, rather than a contractual, basis (The New York Times, 2014).

According to Cooper, the initial structure of one-third of the 1.5% fee created a mechanism that motivated her former husband, Hohn, to achieve the highest possible returns (The New York Times, 2008).

The origin of Hohn’s philanthropic activities dates back to 1986. When he was 20 years old, he visited the Philippines and experienced poverty firsthand. According to Hohn, this was the moment he decided that if he ever had the resources in the future, he would use them to help disadvantaged people (2024).

When I was 20 years old, I met children living in extreme poverty for the first time. Like all children, they were precious—but the circumstances around them, the system they had been born into, had taken opportunities away from them. At that moment, I made a commitment: if I ever had the resources, I would work to address the barriers that prevent children from living healthy, happy lives. This commitment has driven every aspect of my career.

— Chris Hohn (Source: Annual Report 2024 CIFF, 2025)

Hohn was knighted in 2014 for his contributions to philanthropy, receiving the title of Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG).

Personal Life

During his time at Harvard, he met his former wife, Jamie Cooper, with whom he had four children. Hohn and Cooper divorced in 2014, leading to a highly publicized court case. Cooper argued she was entitled to 50% of the assets, while Chris Hohn contended that 25% was the appropriate share. Cooper was ultimately awarded £330 million ($530 million), which represented 36% of Hohn's wealth, then estimated to be between $1.35 billion and $1.6 billion (Royal Courts of Justice, 2014).

Chapter 2. Strategy

Investing in high quality companies—that, in short, is the strategy Chris Hohn and his team pursue today (Hohn, 2025). However, Hohn states he has only come to fully understand what this entails over time.

We invest in high quality companies with predictable free cash flow.

— Chris Hohn (Source: TCI, 2025)

The years following the financial crisis marked a true turning point for Hohn’s investment strategy. In 2008, he was sometimes described as the “undisputed headbanger of the investment community” for his activist approach, which focused on pushing for radical change in underperforming European companies (The Telegraph, 2008).

For example, TCI acquired a stake in ABN AMRO, laying the groundwork for the Dutch bank's eventual breakup and sale. He also intervened in the proposed takeover of the London Stock Exchange by Deutsche Börse. In Chapter 3, we will delve into this activist period of TCI, with a more detailed focus on Hohn's actions concerning the two aforementioned companies.

How does TCI generate alpha?

At the Delivering Alpha Conference in New York in 2013, Chris Hohn explained how he and his team seek to generate alpha in the market.

ⓘ What Is Alpha?

In finance, alpha refers to the outperformance of a portfolio or investment relative to its benchmark index. (The calculation for alpha also adjusts for the investment's underlying ‘risk’, specifically its volatility, or beta; β.)

Alpha is often seen as a measure of a portfolio manager’s or investor’s skill in generating returns that exceed the market’s performance.

Positive alpha indicates that the investor has outperformed the market.

Negative alpha indicates that the investor has underperformed the market.

The search for and creation of alpha is the primary objective of fund managers and investors in individual equities. How did Hohn aim to achieve this in 2013?

Let’s dive in.

First, Hohn states that it’s crucial to understand the sustainability of business models (in this context, sustainability relates to the longevity of business models). Taking a long-term horizon is essential, where persistent high barriers to entry play a significant role. This is in line with Warren Buffett’s philosophy, a concept Hohn calls “time horizon arbitrage.”

Second, TCI has deep expertise in the sectors it focuses on, including infrastructure and consumer goods. According to Hohn, this helps them identify opportunities that emerge in the market over time.

Third, Hohn highlights the topic of concentration. By investing in a select number of high-conviction ideas, Hohn says, concentration can be converted into alpha.

Fourth, Hohn mentions the role of engagement and acting as an owner, taking on an “activist” role in companies. He believes there is an inefficient space in the financial markets where few people are willing to be active, partly due to the risk of reputational damage. Hohn stated in 2013 that TCI is prepared to capitalize on opportunities that arise in this area.

Hohn concludes that when you combine these four elements, you have a set of tools to consistently beat the index with high alpha. (Source: Institutional Investor, 2014).

In this deep dive, we will explore all of the aforementioned components. In the next chapter, we will focus on the element of acting as an owner and the activist role an investor can take. This will be illustrated through several case studies where Hohn and his team at TCI acted as activist shareholders. What lessons did Hohn learn from this period?

Chapter 3. Shareholder Activism

Hohn argues that most investors take a passive approach to being shareholders. He and his team at TCI have, however, made various attempts to instigate change within companies. He stresses that the very concept of being a shareholder, in essence, means being a partial owner of a company. As such, shareholders must act as owners, according to Hohn.

TCI’s activist efforts range from submitting proposals to increase dividends and expand share buyback programs to attempting to block a proposed acquisition or even pushing for a company's breakup.

Most investors are just passive. Bad things will happen, and they don’t say anything or do anything. I’ve seen it all in my career. They don’t act as owners.

— Chris Hohn

ⓘ What Is Shareholder Activism?

Shareholder activism is an approach to investing where shareholders, often financial institutions, use their influence to force changes within a company. This doesn't just involve financial causes, but often includes issues like corporate strategy, governance, compensation policies, or sustainability.

In summary, activist shareholding exists on a spectrum, according to Hohn. On one end is hard activism, where shareholders exert pressure by removing board members or CEOs, forcing mergers or breakups, or even demanding the sale of the entire company. This type of activism is often characterized by confrontation, legal proceedings, or public campaigns.

On the other end is soft activism, which focuses on building relationships, dialogue, and cooperation with management. Here, shareholders might submit proposals at the annual general meeting or engage in private discussions with the board of directors about improvements in capital allocation, transparency, or sustainability.

However, if a call for soft activism is not heeded, a shareholder may resort to harder measures if no progress is made.

The following sections present a number of case studies where TCI adopted an activist approach, always with the ultimate goal of maximizing shareholder value.

3.1 Deutsche Börse

At the end of 2004, Deutsche Börse announced its intention to acquire the London Stock Exchange (LSE) (Deutsche Börse Group, 2005, 2005; The New York Times, 2005). However, on March 6, 2005, Deutsche Börse withdrew its takeover bid, a decision in which TCI played a significant role. The German financial regulator, BaFin, wrote the following about TCI's actions regarding Deutsche Börse:

[...] In 2005, BaFin conducted an investigation which centred around Deutsche Börse AG. The case provoked considerable public interest. The investigation was in response to the conduct of several fund management companies linked to the UK hedge fund The Children’s Investment Fund Management (TCI), whose intervention prompted the withdrawal of Deutsche Börse AG’s takeover bid for the London Stock Exchange and the resignation of the company’s CEO Werner Seifert. (Source: BaFin Annual Report, 2005)

TCI was against the acquisition of the LSE and, through its actions, sought to prevent it from proceeding. After the takeover bid was withdrawn in March, Deutsche Börse received multiple proposals (demands) in the spring of 2005 from a number of activist shareholders, including TCI.

These demands related to implementing share buyback programs, as well as the dismissal of members of Deutsche Börse's Executive and Supervisory Board (BaFin, 2005). As a result, the then-sitting CEO, Werner G. Seifert, left Deutsche Börse on May 9, 2005. Later that same year, the chairman of the supervisory board also resigned.

Werner G. Seifert, the former CEO of Deutsche Börse, co-authored a book with Hans-Joachim Voth about this period, titled Invasion of the Locusts: Intrigues - Power Struggles - Market Manipulation. How Hedge Funds Attack the German Corporation (2007).

In his book, Seifert uses the term “Heuschrecken” (locusts) to describe the short-term, aggressive stance of hedge funds. In his view, these funds swarm into companies, extract value, and then leave them in a worse, damaged state. Chris Hohn, in particular, receives sharp criticism in Seifert's book. According to The Telegraph (2008), Seifert described Hohn as an “unbelievably arrogant and a typical loner.”

Following the book’s publication, The New York Times (2006) published an article noting that hedge fund managers who have worked with Hohn consistently praise him for his diligence and intelligence. At the same time, the newspaper also observes that some of these managers find his social skills less refined than those of some other London residents.

Germany's Manager Magazin (2005) reported that while Hohn was present at Deutsche Börse's 2005 shareholder meeting, he did not appear publicly or participate in the Q&A session to answer investor questions. The magazine states that Hohn is known for being strategically far-sighted, stubborn, and uncompromising when it comes to what he believes is right.

When asked whether TCI and the other hedge funds involved had improperly collaborated to pressure Deutsche Börse, the German financial regulator, BaFin, announced after an investigation that it had insufficient evidence to bring a lawsuit:

BaFin was unable to find sufficient proof to back up the theory that the fund management companies had been acting in concert. In particular, the evidence available could not establish, beyond dispute, that the funds in question had any further-reaching entrepreneurial interest, or an overall plan for Deutsche Börse AG (Source: BaFin Annual Report, 2005, p. 180)

Partly due to TCI's actions, Deutsche Börse's share price increased by more than 90% in 2005, from €44 on January 1, 2005, to over €84 by the end of December of that year.

3.2 ABN AMRO

On February 20, 2007, TCI wrote a letter to the management of the Dutch bank ABN AMRO. In the letter, TCI pointed out that since May 2000, ABN AMRO had delivered a cumulative share price return of 0%, excluding dividends, while a peer group and the Dow Jones Euro Stoxx Banks Index had generated returns of approximately 44% over the same period. According to TCI, this "terrible shareholder return" was due to the fact that ABN AMRO's shares had experienced no intrinsic value appreciation; earnings per share had remained roughly flat, driven by the lack of benefits from failed restructurings and acquisitions.

We believe that it would be in the best interests of all shareholders, other stakeholders and ABN AMRO for the Managing Board of ABN AMRO to actively pursue the potential break up, spin-off, sale or merger of its various businesses (or as a whole). [...] We believe that this strategy would not only create significant shareholder value but also would best serve all the stakeholders who otherwise would suffer over the long term from the structurally declining competitive position of ABN AMRO.

— Patrick Degorce, TCI Fund (Source: TCI’s letter to ABN AMRO, February 20, 2007)

TCI submitted five proposals for ABN AMRO's Annual General Meeting (AGM) on April 26, 2007:

The ABN AMRO Managing Board must investigate whether the sale, spin-off, or merger of key business units could maximize shareholder value.

The proceeds from the sale of business units must be returned to shareholders via share buybacks or a special dividend.

The board must investigate whether the entire company could be sold or merged to maximize shareholder value.

The board must report on the outcome of the aforementioned investigations within six months of the AGM.

The board must refrain from any substantial business acquisitions for six months following the AGM, including the rumored takeover of Capitalia SpA.

With nearly 68% of the votes, the proposal to have ABN AMRO's management explore options for a sale, spin-off, or merger of business units was approved (De Volkskrant, 2007).

In doing so, TCI would play a significant role in the eventual split and sale of the Dutch bank: ABN AMRO was sold in the fall of 2007 to a consortium of Royal Bank of Scotland, Fortis, and Banco Santander. This consortium acquired ABN AMRO for €71 billion (Reuters, 2007).

This acquisition price amounted to €38.40 per share. According to Hohn, TCI earned $1 billion from its investment in ABN AMRO (NBIM, 2025).

They didn’t know what they were doing. We didn’t know what we were doing. It was all madness.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

According to Hohn, many activist shareholders ultimately become activists in bad companies. He concludes that the underlying quality of a business is what truly matters, so there is little point in focusing on “B-companies.” It makes even less sense to be an activist shareholder in a poor industry, Hohn concludes (2025).

Reflecting on TCI's role in previous activist campaigns, Hohn decided to adopt a more cautious stance when initiating new, initial positions in companies.

While we’re not going to rule out taking an activist stance on existing investments, like Deutsche Börse, we are going to be more cautious about it when we look at making new investments, because quite frankly activism is hard.

— Chris Hohn (Source: Alpha, 2008)

3.3 Safran & Zodiac Aerospace

In 2018, Safran, a company that had been in TCI's portfolio since 2012, intended to acquire Zodiac Aerospace (Safran, 2018). According to Hohn, shareholder engagement should also include stopping “stupid things.” He believed that Safran’s valuation at the time of the proposed takeover was too low, while Zodiac's was extremely overvalued, with “the price being ridiculous” (Hohn, 2025).

The proposed structure, which involved funding the acquisition with Safran shares, would have led to a significant loss of value for existing Safran shareholders, which Hohn called “doubly bad” (2025). TCI fought the deal, resulting in a much lower acquisition price paid in cash.

An adverse side effect was that Zodiac Aerospace sued Chris Hohn personally, as well as TCI's general counsel, for €100 million each. The case was heard in a Paris court. As Hohn remarked, “It's not for the faint-hearted” (2025).

TCI had been invested in Safran for several years, so its actions could be classified as defensive activism. I believe this is the best way to act as an owner of a company: to share your vision and ideas for the long-term prosperity of all shareholders, including protecting them from potentially less-than-rewarding management decisions.

We act as owners. We’re always active owners. We’re interested. We’re engaged.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

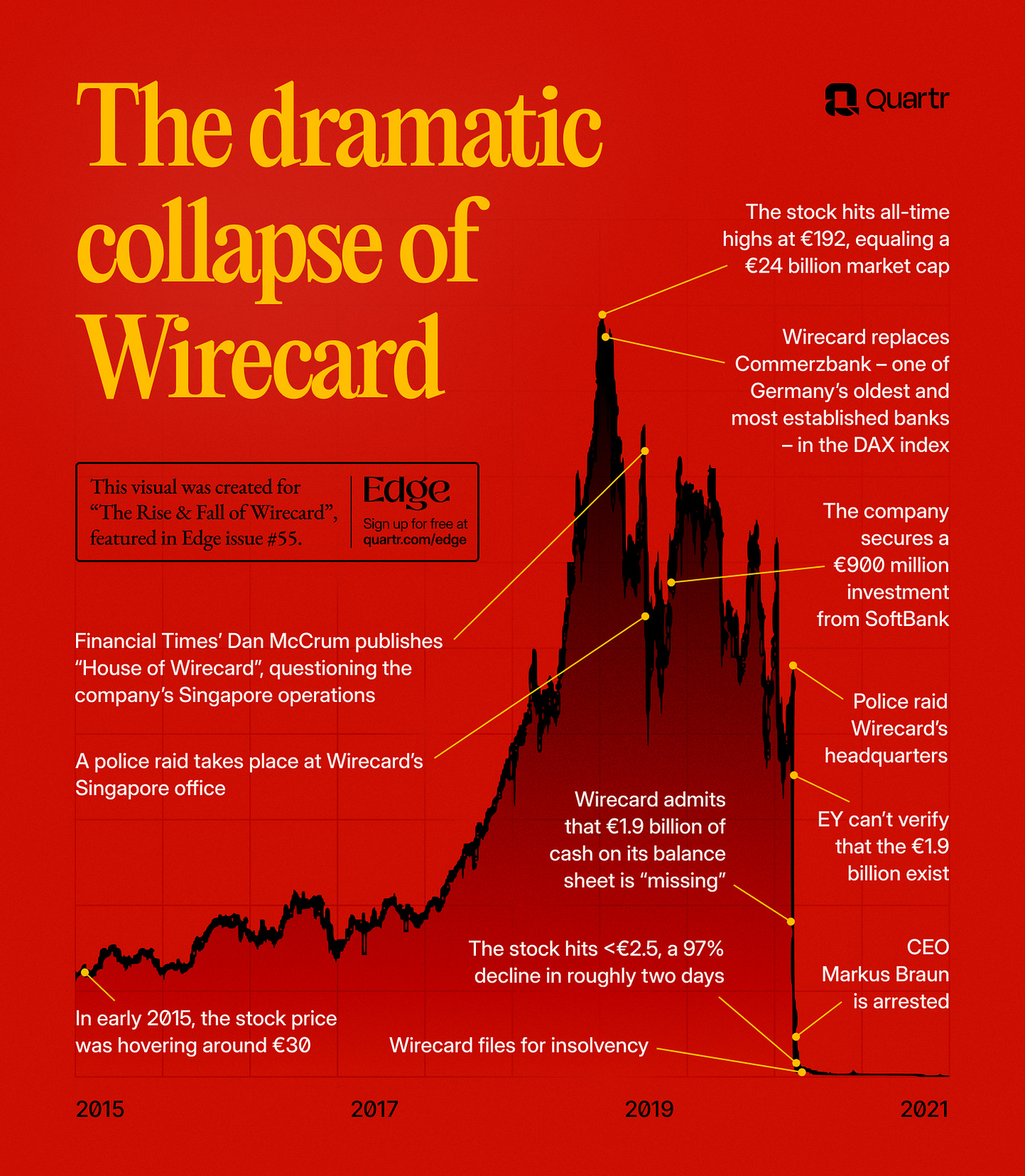

3.4 Wirecard

In early 2020, TCI took a short position in Wirecard. In May 2020, TCI also filed a criminal complaint against Wirecard's management (Reuters, 2020). Wirecard responded, stating that TCI's allegations were “completely unfounded.” “Wirecard therefore regards the filing as a purely tactical manoeuvre of a short seller,” the German fintech company claimed (The Financial Times, 2020).

In April 2020, TCI had already urged the supervisory board to suspend the CEO, as the auditing firm KPMG could not verify whether a significant portion of Wirecard's profits were real.

In our opinion, the necessary intervention is now to remove the CEO from all management duties.

— Chris Hohn (Source: The Financial Times, 2020)

On April 29, 2020, the short position of TCI stood at 1.53% of Wirecard's market capitalization (MarketScreener, 2020).

Hohn reflects on his experience with Wirecard by stating that shorting stocks is not a great business model (2025). Even if you are right, you can find yourself in a situation where you cannot maintain a short position long enough to be proven right. This is because a stock's price can trade irrationally for an extended period, especially when institutions and their executives try to defend their narrative for as long as possible.

Asymmetric Risk & Reward

Another factor is that shorting has a maximum upside of 100% and a theoretically infinite downside, making it an unappealing investment strategy to focus on as a primary approach. In a dinner with Warren Buffett, Hohn learned that Buffett and Charlie Munger had seriously researched shorting but came to the same conclusion: shorting stocks is too difficult because it involves an additional dimension—the psychology and (ir)rationality of investors on a short term horizon (Hohn, 2025).

I share the same view as Hohn, Buffett and Munger on shorting: while taking a long position has a positive asymmetry that you can profit from over the long term, shorting a stock has a negative asymmetry where time can be your biggest enemy in the short term.

3.5 Alphabet

On November 15, 2022, Chris Hohn wrote a letter to Sundar Pichai, CEO of Alphabet, in which TCI had held a position since 2017, valued at over $6 billion as of November 2022. The letter's core message was that the company's cost base was far too high and that Alphabet's management needed to take “aggressive action” to reduce it.

Hohn also argued that Alphabet's management should allocate more cash to share buyback programs: “Alphabet still has over $116 billion of cash on the balance sheet. Alphabet’s large cash balance is serving neither shareholders nor the company,” urging the company to become “cash neutral,” similar to Apple. This was particularly relevant given that Alphabet was trading at just 16 times its 2023 EPS, making the “stock very cheap,” according to Chris Hohn (2022).

Two months later, on January 20, 2023, Alphabet announced “A difficult decision to set us up for the future” (Alphabet, 2023). On that day, it was revealed that Alphabet would lay off approximately 12,000 employees.

After this news was released, Chris Hohn sent a thank-you letter to Pichai: “I have appreciated our recent dialogue concerning Alphabet’s cost base. I am encouraged to see that you are now taking some action to right size Alphabet’s cost base and understand that it is never an easy decision to let people go” (TCI, 2023).

Despite acknowledging that the layoff of 12,000 employees was a step in the right direction, Hohn stated that management would need to go further to normalize the significant headcount growth over the previous five years—from over 100,000 employees. “I believe that management should aim to reduce headcount to around 150,000, which is in line with Alphabet’s headcount at the end of 2021.”

As of December 31, 2023, Alphabet had 182,000 employees worldwide (Alphabet, 2024).

In Q1 2023, TCI significantly reduced its stake in Alphabet by selling 47 million shares, which accounted for 15% of TCI's U.S. listed portfolio at the time. Sales also occurred in Q2 2023 and Q3 2023, representing approximately 2% of TCI's portfolio. Since then, TCI has engaged in small buys and sells. As of June 30, 2025, Alphabet ($GOOG + $GOOGL) had a weighting of 5.6% in TCI's U.S. listed portfolio (Dataroma, 2025).

3.6 Conclusion

Most investors accept what happens without fighting for their own views, principles, and values. Of course, this depends on the size of your stake in a company, though Hohn notes that even with a small stake of a few percent, a good idea can gain the support of large shareholders who are typically more passive but are willing to back strong viewpoints. For example, TCI, with only a 1% stake, was able to initiate the unlocking of value at ABN AMRO.

Hohn states that TCI's current relationship with the companies it invests in is generally very constructive. Reflecting on his past approach, Hohn says, "I've learned that hardcore activism is not a great thing."

However, when necessary, TCI still applies a form of shareholder activism, such as in the proposed acquisition of Zodiac Aerospace by Safran, in which TCI has been a shareholder for many years.

You could trace a transition in TCI's approach over the years, shifting towards a more defensive stance rather than actively seeking out companies where a certain value might be unlocked through a heavy-handed form of shareholder activism.

Activism is now more opportunistic rather than fundamental for us.

— Chris Hohn (Source: Institutional Investor, 2022)

Over time, TCI has refocused on quality companies, which has also inherently reduced TCI's activist nature. As Hohn puts it, "Good companies generally tend to be well run" (2021).

Chapter 4. Moats, “The Real Thing”

With the lessons of the past in mind, we've now arrived at what Hohn calls “The Real Thing”: moats, and their sustainability (2025). This sustainability can be assessed by looking at the development of a company's moat; its slope.

In addition to a company's moat and its slope, another key pillar of my own investment strategy is a firm’s growth and its exposure to positive secular trends. Is management steering the company in the right direction?

I believe these two factors—moat and growth—form a powerful combination and lay a solid foundation for a company's ability to increase its intrinsic value over time. Businesses where both these elements are developing positively will be able to create significant intrinsic value for a long period—the compounders of our world.

Long term value creation = Σ [ Moat x Growth x (ROIC -/- WACC) ] +/- Other Factors

While the formula above is not a real equation, it provides a framework to highlight the most important elements in my research process. A brief explanation follows below.

ⓘ Explanation of the Formula

For long-term value creation, the longevity of a moat is paramount. Without a stable or positive slope, a company's moat will eventually become a factor of zero, causing the entire value creation formula to equal zero.

In my view, the moat forms the foundation: every company should have one to create sustainable, long-term value. Therefore, I focus exclusively on companies that I believe possess a massive moat. This is reflected in my qualitative research approach, which centers on the question of whether a company's moat is developing positively or negatively and how I assess its future trajectory. In doing so, I try to account for all forces that will be exerted on the business in the future.

With a strong moat as the foundation, a company's growth engines are then able to create value over a long period. These engines include organic growth (via price and volume) and, potentially, growth through M&A.

The profitability of this growth is a crucial factor. Only companies that can achieve growth with a return higher than the cost of that growth will create real value.

Additionally, other factors, such as the quality of management and its optimization of capital allocation, as well as external issues like regulation, play a role in the overall value creation process.

In the following section, we'll first delve into Hohn's thoughts on growth, and then move on to a deeper discussion of moats. As we proceed, you'll see how these two forces are interconnected. In the world of quality investing, many elements are connected.

4.1 Growth

According to Hohn (2025), many investors get confused by the idea that they should simply focus on growth. He uses the example of airlines, a sector that has grown significantly over the past century but has collectively failed to generate much profit.

Growth alone is no guarantee of value creation. Hohn emphasizes that it is essential for companies to have strong barriers to entry that protect their business. Furthermore, it's crucial for companies to add value on a sustainable basis. We will explore this in more detail later.

Growth can be broken down into two contributors: price and volume (for now, we'll exclude growth from M&A). It's important to distinguish between these two growth drivers when analyzing companies, Hohn says (2025). Many companies may grow significantly, but this growth can come with high costs, making it “profitless growth.” Moreover, Hohn argues that growth without barriers to entry is an undesirable combination.

According to Hohn, most companies lack pricing power; if these companies are lucky, they can raise prices in line with inflation.

Real pricing power above inflation can be very valuable.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

A special group of "super companies" can price their products and/or services above the rate of inflation. As Warren Buffett has taught us, Hohn says, this is the test of whether a company truly has a moat.

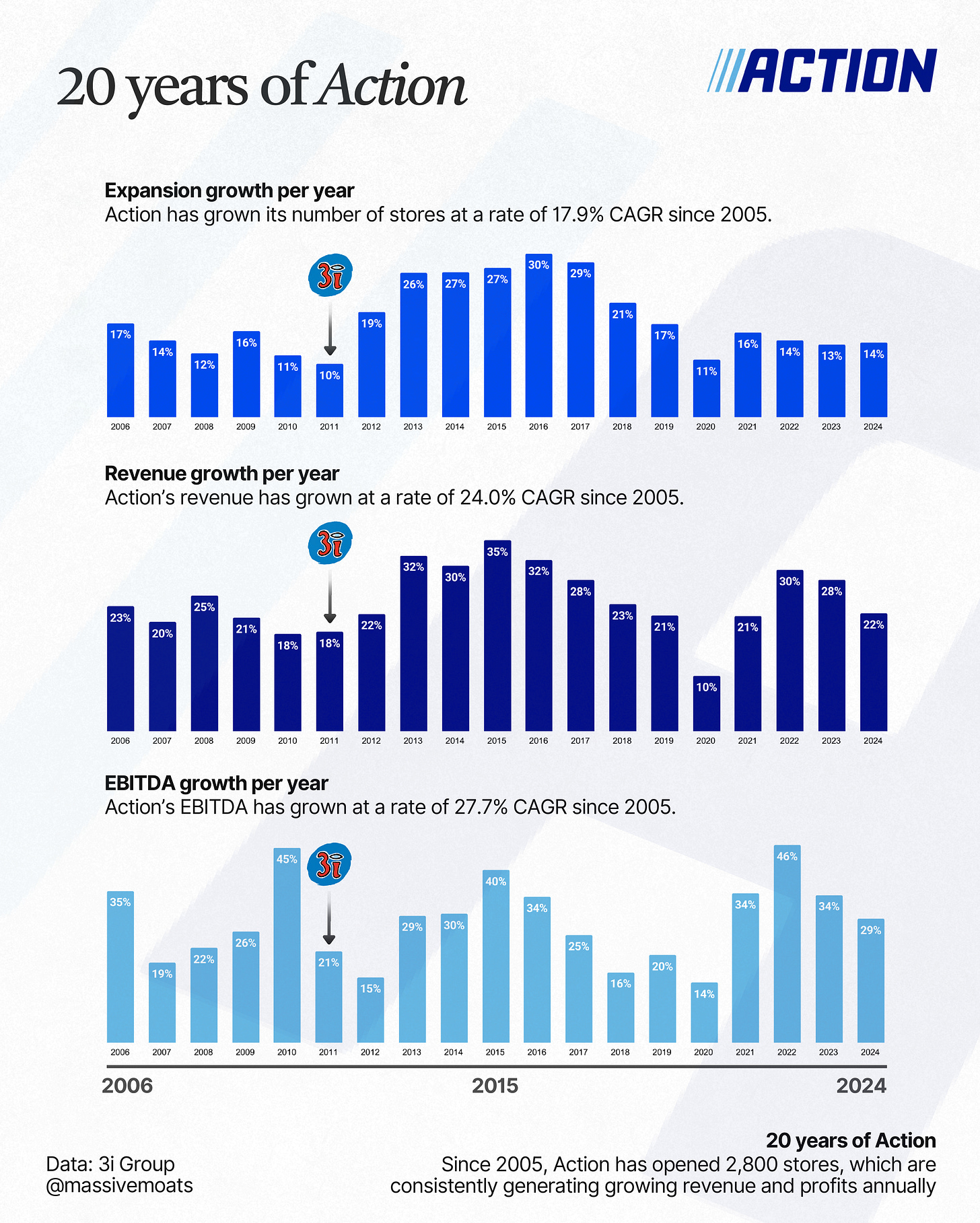

I largely agree with this, though I would add the nuance that some companies can build a strong moat precisely through price reductions, where they create value through a growth in volume, as is the case with 3i Group's portfolio company, Action. Similarly, Costco, which maintains a fixed 14-15% markup on its purchase prices, bases its value creation for stakeholders on volume growth.

Hohn asserts that real price growth above inflation is highly valuable because it creates benefits through operating leverage: for example, a 1% price increase at a company with a 20% profit margin leads to 5% profit growth (2025). I have further elaborated on this scenario below.

ⓘ Example Scenario

Imagine a company that can increase its prices 1% faster than the rate of inflation. In this case, if the company has a profit margin of 20%, its profit will grow 5 times faster than its revenue. (This scenario ignores other variables, such as volume growth, and assumes the company's costs increase proportionally with inflation).

Assume the inflation rate in a given year is 3%, and a company increases its revenue by [3% + 1% =] 4% in that year, from $1 billion to $1.04 billion, entirely driven by price increases. In this case, the company's profit will increase from $200 million (at a 20% profit margin) to $216 million (at an approximate 20.77% profit margin). This $216 million is calculated by subtracting the company's cost base of [$800 million plus 3% cost inflation =] $824 million from its total revenue of $1.04 billion.

In other words, the company's revenue increased by 4%, while its profit increased by 8%. Of this profit growth, 5% is purely driven by the 1% extra price increase above inflation [8% adjusted for 3% = 5% extra profit growth].

In real terms, adjusted for 3% inflation, this amounts to a profit growth of approximately 5%. Companies without pricing power would have seen their revenue rise by no more than 3%, in line with inflation-driven price increases, resulting in little to no real profit growth or even negative real profit growth.

To achieve this as a business, you must add a certain value. Without consumer surplus, there are no opportunities for pricing power—let alone for demand at all.

Essentially, it all comes down to a business protecting its consumer surplus. After all, if a company hasn't built a strong moat, other firms can effortlessly enter its market and serve the consumer with similar products or services at a slightly lower price.

It boils down to a combination of a strong barrier to entry and the sustainable, high value that companies deliver with their products. According to Hohn (2025), only with these variables does growth have any value.

4.2 Moats

Hohn argues that companies whose moats are eroding will not be able to create long-term value. The durability of a company’s moat is, therefore, crucial.

The real thing is sustainability of moats.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

Companies in highly competitive sectors will fight for the same customers, revenue, and value-creation potential. In an equal economic playing field—capitalism—markets with intense competition will experience a "race to the bottom," resulting in very low value creation at the company level for the firms involved.

This is why it's important for companies to possess specific features, that differentiate them from competitors, or to build structures with high barriers to entry. These come together in the five types of moats: Cost Advantage, Network Effects, Switching Costs, Intangible Assets (IP), and Efficient Scale.

Even when companies protect their valuable, value-creating activities with a strong moat, competitors will always try to get a piece of the action. They do this through direct competition, but also via disruption—where an innovative product or service changes the market and replaces existing companies—or substitution—where a product or service is replaced by an alternative that serves the same function.

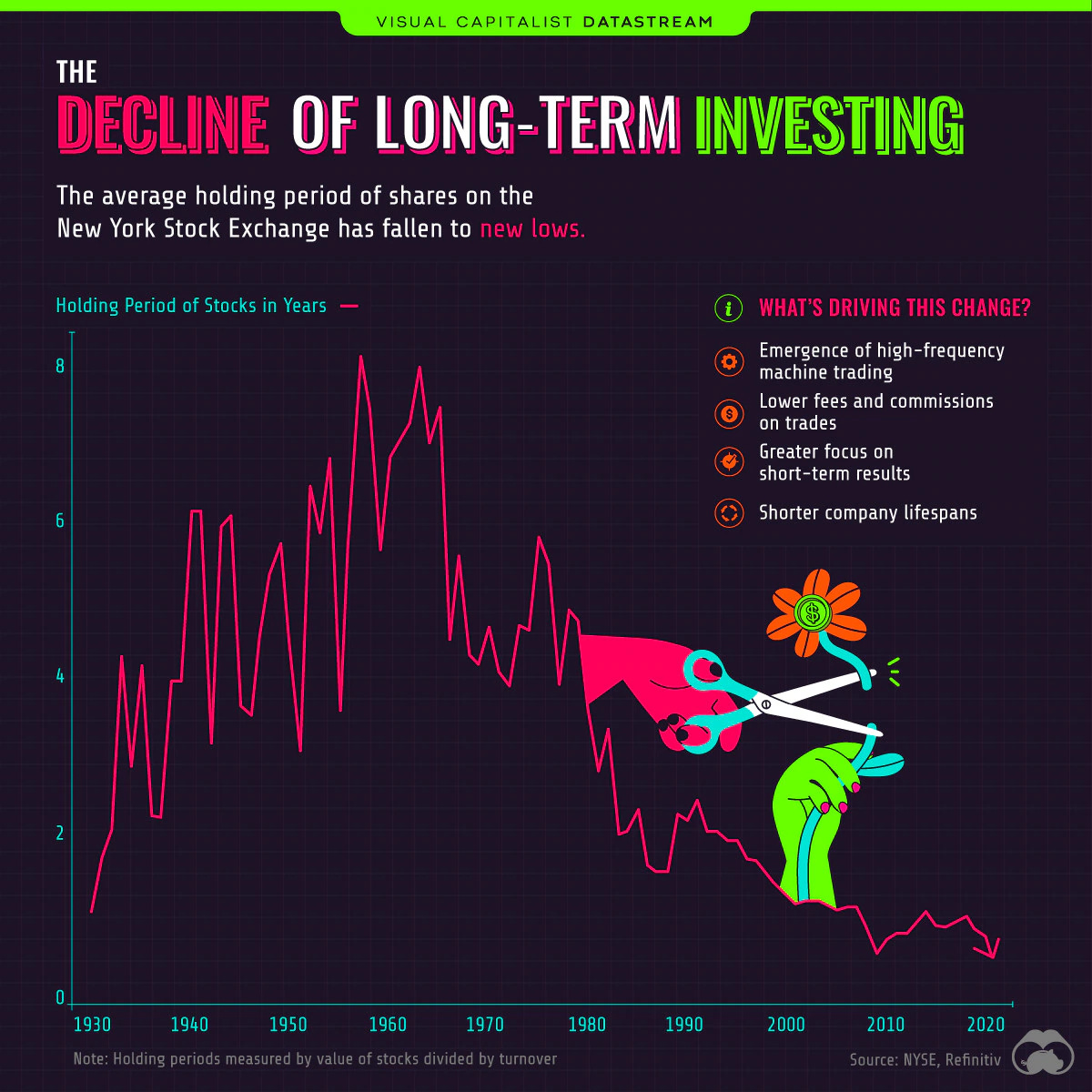

Therefore, competition, disruption, and substitution are powerful forces that investors must interpret correctly. Hohn indicates that many investors underestimate these forces because they have a short-term focus.

Most companies—95% of them—are mediocre or bad companies. They meet their cost of capital, but they are not super companies.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

Quality > Value

Buying shares of poor to mediocre companies at a significant discount to, for example, their replacement value can be profitable. However, Hohn, who has done this in the past as well, no longer trusts this approach. Specifically, he has no confidence in the earnings power of these companies, as it is unpredictable (2025).

With experiences similar to Hohn’s, I now look back on certain positions in my past portfolio with a comparable perspective. What I have learned is that, much like shorting stocks, you can eventually be proven right, but the path to getting there is highly unpredictable. For example, I was “proven right” in the case of Prosus’s acquisition of Just Eat Takeaway (regardless of the bid size or its justification).

I have also consistently underestimated the time component—the power of time in our journey as investors. First, in the form of opportunity costs: during the same period, I could have invested in high-quality companies. Second, while waiting to be proven right (i.e., for value to be unlocked), a company may continue to destroy value, or the market may price the stock significantly lower due to new negative developments, or simply due to a lack of value-enhancing progress.

In the case of Just Eat Takeaway, the company was in a transition period where its intrinsic value was increasing (by eventually making the right decisions), but this was not reflected in the stock price by investors—until Prosus came along with a 63% premium offer and capitalized on it.

In conclusion, as an investor focusing on these types of companies, you remain heavily dependent on other investors for (short-term) results. It can happen that investors systematically offload a stock, allowing another party to take it private at a bargain. This could be well below your purchase price, resulting in personal value destruction. The question that remains with these experiences in mind is: Why would you want your wealth growth to be primarily dependent on the short-term actions of others (i.e., management or other investors)?

Time can be your greatest enemy in such situations. At the same time, it can also be your greatest ally: by investing in companies that have built a strong value-creation flywheel, whose moat continues to widen, you increase the likelihood of a favorable future outcome—just as Nick Sleep (Nomad Investment Partnership) would put it.

Hohn argues that certain sectors are more susceptible to disruption than others. He considers the technology sector to be one he approaches with caution, resulting in low to no exposure to technology companies in TCI's portfolio.

I agree with Hohn that as investors, we must properly assess which potential future developments will affect which types of companies, as well as the magnitude of that effect (probability times impact).

AI will increase disruption in ways we can’t even predict.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

I share Chris Hohn's view that AI will cause disruption in ways we can't yet predict. I've written about this frequently. Based on what I've learned recently, here is my current perspective on AI.

↻ My Vision on AI (September 2025)

➢ Standardized human processes will be largely automated. In the coming decade, AI will take over most routine, standardized, or semi-human tasks. This won't be a direct one-to-one replacement, as the process may change, but the outcome—solving a problem—will be the same. Hohn himself cites call centers as an example, stating, "Call centers will all go bankrupt" (Hohn, 2025). I share this view with Hohn, whereby I expect that the underlying process for solving the problem will take a different form, for example through AI agents communicating with each other.

➢ Software development will change fundamentally. Hohn suggests that the demand for human coders could plummet, as AI may enable the same output with half the staff (Hohn, 2025). We are already seeing these benefits in terms of time efficiency and, increasingly, higher quality from AI-driven code. The traditional model where software companies create value through years of R&D and scalable online services will be pressured. What once took months or years to build can now be accomplished in just a few hours with AI. In the future, it may take only a fraction of that time.

➢ Many SaaS companies will lose their competitive edge. In a world where software can be created significantly faster, many SaaS businesses will no longer have a competitive offering if they can't capitalize on their accumulated software IP or economies of scale, as these advantages will become commoditized. Only companies that have built high switching costs around their services will survive, and even these could be threatened as AI becomes more advanced. In my opinion, a moat based on strong network effects will be the most resilient against AI in the technological domain, provided the facilitating companies continue to offer the best possible service with their network or platform.

➢ AI will amplify the value of human creativity. In a world of increasing uniformity, there will be more room for companies that can differentiate themselves through craftsmanship and human creativity. I expect these companies to increase their profitability through two channels: (a) greater demand for their products and (b) lower overhead costs driven by AI. Hohn states that AI will increase the productivity and lower the cost base of all companies (Hohn, 2025). I believe this is true for companies that are able to adopt AI while retaining their unique value proposition. I foresee greater long-term profitability, driven by positive secular growth and cost savings, for companies like Hermès and LVMH.

➢ Continuous evaluation of a company's moat is essential. I expect that B2C SaaS companies like Duolingo will face significant challenges, as I anticipate that a personal AI agent will be far better equipped to create tailor-made language learning sessions for users—customized to the context of a user’s day and the devices they have available and prefer at any given moment. With weak network effects (Duolingo is primarily an app for individual use) and minimal switching costs, I would not want to be invested in this company. Perhaps I am thinking too far ahead, but in my view, considering the risks that AI poses to companies in one’s portfolio is something investors should actively engage in: continuously testing future scenarios that could erode a company’s moat and its very reason for existence.

➢ Are we heading toward AGI? According to Demis Hassabis, the CEO of DeepMind, the answer is yes. He estimates there's a 50% chance of achieving AGI within five years (2025). To create true AGI, I believe we first need to understand how our own brains work and how we use our developed intelligence to create new knowledge. My view on this topic is more aligned with that of David Deutsch and Naval Ravikant.

A better chess playing engine is one that examines fewer possibilities per move. Whereas an AGI is something that not only examines a broader tree of possibilities but it examines possibilities that haven’t been foreseen. That’s the defining property of it. If it can’t do that, it can’t do the basic thing that AGIs should do. Once it can do the basic thing, it can do everything.

— David Deutsch (Source: David Deutsch: Knowledge Creation and The Human Race, Part 1, Naval, 2023)

About AGI: [...] it’s creating new knowledge that you did not intend it to create, and it’s causing it to behave as a complex and autonomous entity that you cannot predict or control.

[...] that is the mark of an intelligent thinking thing that is creating its own new knowledge.

— Naval Ravikant (Source: David Deutsch: Knowledge Creation and The Human Race, Part 1, Naval, 2023)

Despite this, I believe certain technology companies can create significant value in the coming decades. Unlike Hohn, I have a high exposure to technology companies.

Irreplaceable Physical Assets

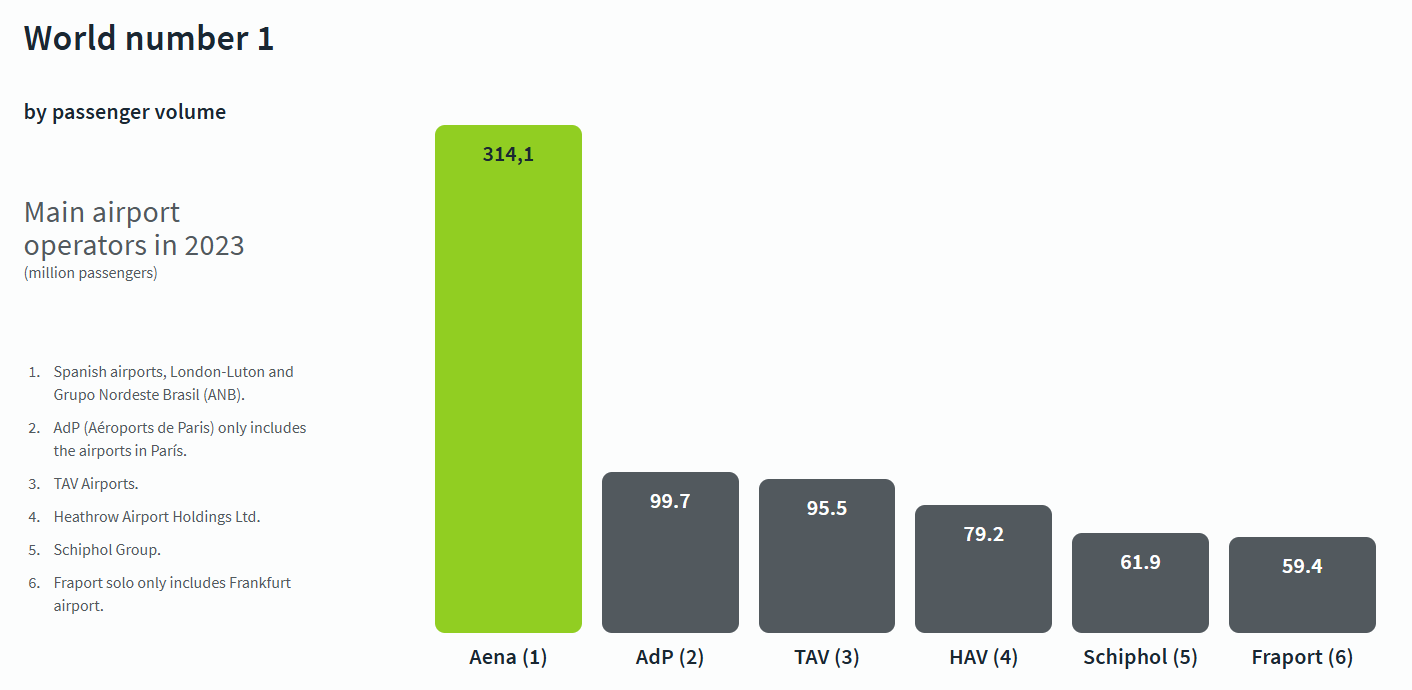

Hohn himself cites infrastructure as one of the sectors he finds most interesting. He gives examples like toll roads, airports, railroads, transmission lines, and cellphone towers, which he labels as "natural monopolies" (2025). For instance, TCI participated in the IPO of the Spanish airport operator Aena in 2015, taking a 6.7% stake (Reuters, 2015) at a valuation of a 15% FCF yield, because as Hohn states, "valuation matters" (2025).

Hohn is drawn to the physical component of infrastructure companies’ assets, where valuation can be approached through the book value of the firms’ tangible holdings.

The high capital expenditure requirements for physical assets are not a reason to immediately rule out these companies, according to Hohn. What matters is the return on these investments, which are often higher at companies with strong moats that protect these ROICs.

Intellectual Property (IP)

In the domain of intellectual property (IP), Hohn focuses on companies that possess IP so advanced that it is extremely difficult to replicate.

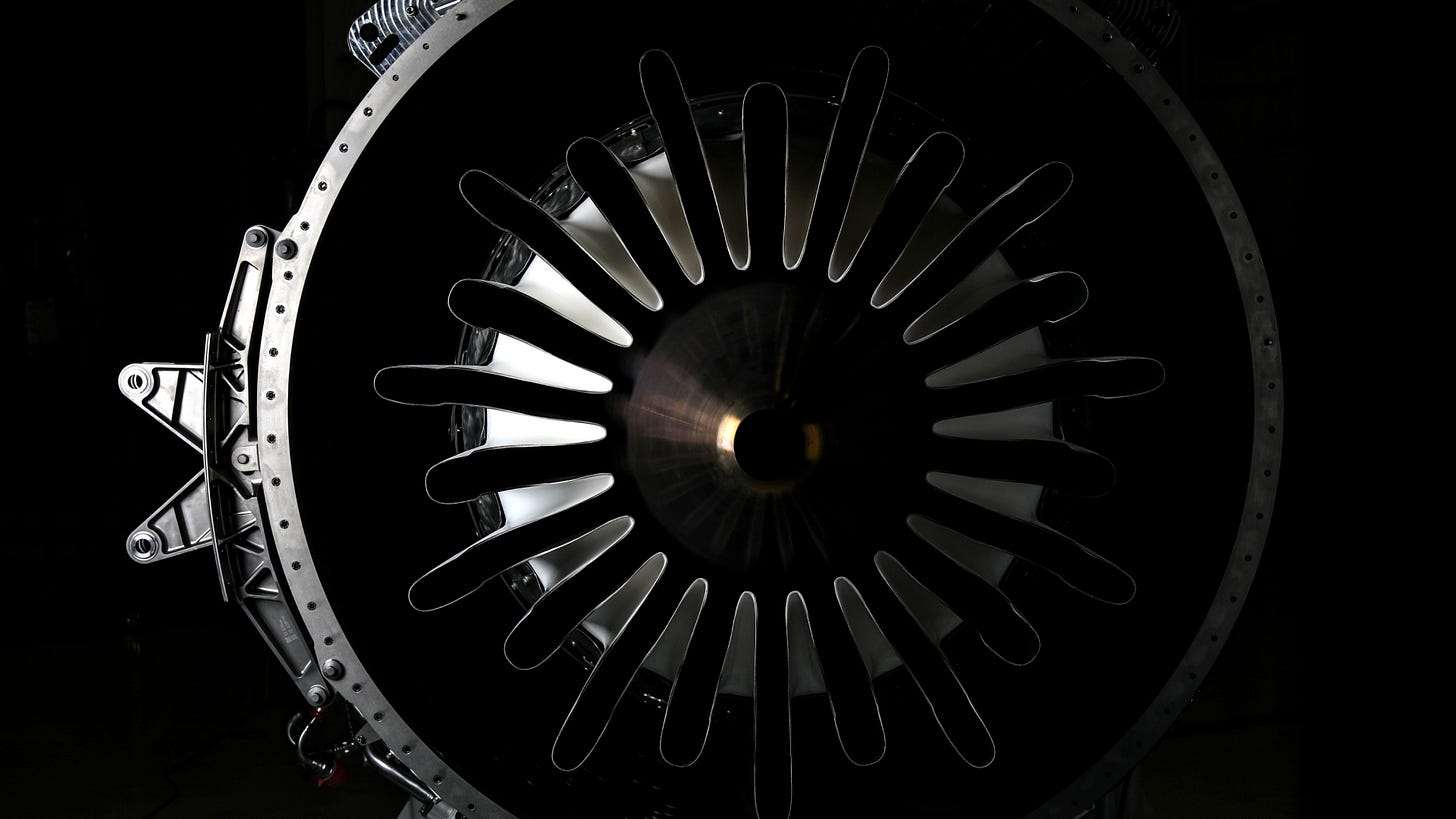

As an example, Hohn names the aerospace industry, specifically aircraft engine manufacturers. According to Hohn, the barriers to entry are extremely high due to the complexity of production, involving many thousands of specific parts. As a result, no new entrants have come into the market for narrow- and wide-body aircraft engines in the last 50 years (Hohn, 2025).

As of June 30, 2025, GE Aerospace was TCI's largest holding (sec.gov, 2025). Safran Aircraft Engines, which has a 50-50 joint venture with GE Aerospace called CFM International, is also a valuable addition to TCI's portfolio. According to Hohn, Safran has delivered a return of more than 20% CAGR over the last 13 years (2025).

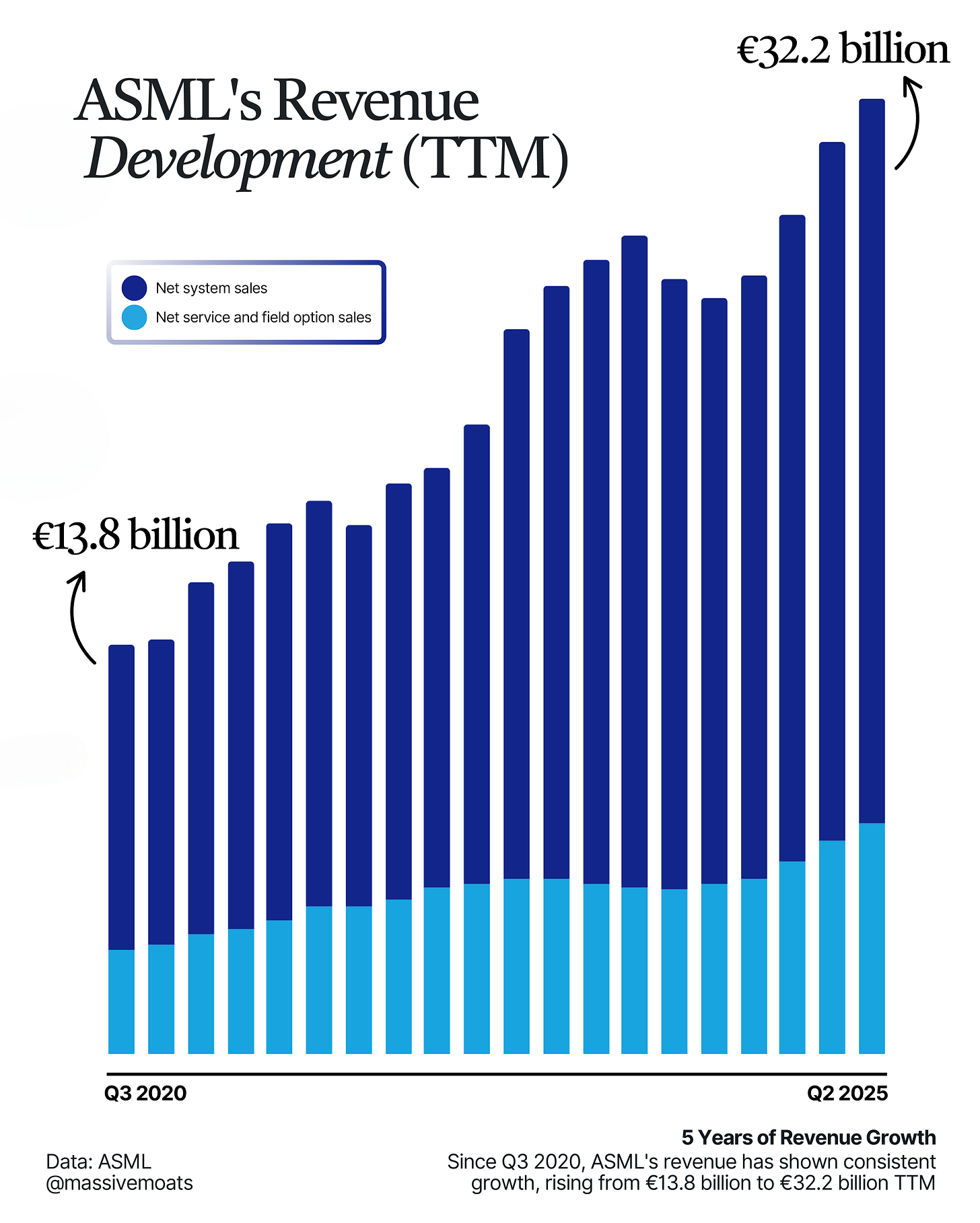

Hohn also cites Installed Base as a high barrier to entry, where companies benefit from an established base of (physical) infrastructure and continue to profit from high switching costs and potential additional service revenue. Hohn cites the aircraft engine market as an example (2025). A company like ASML would also fall under this category, with an installed base of over 6,000 machines.

Brands (IP)

According to Hohn, brand strength can also constitute a barrier to entry, though not every brand is equally robust. Hohn cites McDonald’s as an example of a strong brand. He adds that some brands can be so powerful that they prove to be durable over time (2025).

In my view, however, the IP moat based on brand strength is among the most difficult to assess accurately. For instance, Abercrombie & Fitch was out of favor for a long period, yet managed to successfully reinvent itself—an evolution that was mirrored in its share price. That said, the outcome could easily have been the opposite had consumers not responded positively to this repositioning. Ultimately, it is the end consumer who determines which brands prevail and for how long.

The Lindy effect suggests that brands with a longer history may also have a higher likelihood of continued success. Nevertheless, I believe that the future trajectory of a brand-based moat remains challenging to define. Consider, for example, the luxury industry and its recent performance in the Asia-Pacific region. How should one account for such (potentially short-lived) deviations when measuring the slope of their moat? Personally, I remain undecided on this point.

Economies of Scale

According to Hohn, a company benefiting from economies of scale does not necessarily possess a competitive moat.

I agree with Hohn that a large scale, by itself, does not guarantee a moat. Many market leaders have existed in the past, only to be partially or completely displaced by competition, disruption, or substitution.

Consider companies such as Kodak, Nokia, Blockbuster, BlackBerry, and Yahoo. Or, as Hohn recently pointed out (2025), Seat Pagine Gialle S.p.A., an Italian Yellow Pages publisher. Despite its dominant market position, the company was disrupted by the advent of new technologies and the rise of the internet, as new entrants solved the same problem in a different way. Seat Pagine Gialle saw its market capitalization collapse from $50 billion to virtually zero.

The key lesson here is that corporate management must steer their ship—whether a nimble speedboat or a massive container vessel—through the constantly shifting waves of an ocean filled with infinite possible future scenarios. It is about anticipating the waves that are close at hand, with their immediate risks and opportunities, as well as detecting distant waves, in order to prepare the ship for changes that will unfold over a longer period.

Network Effects

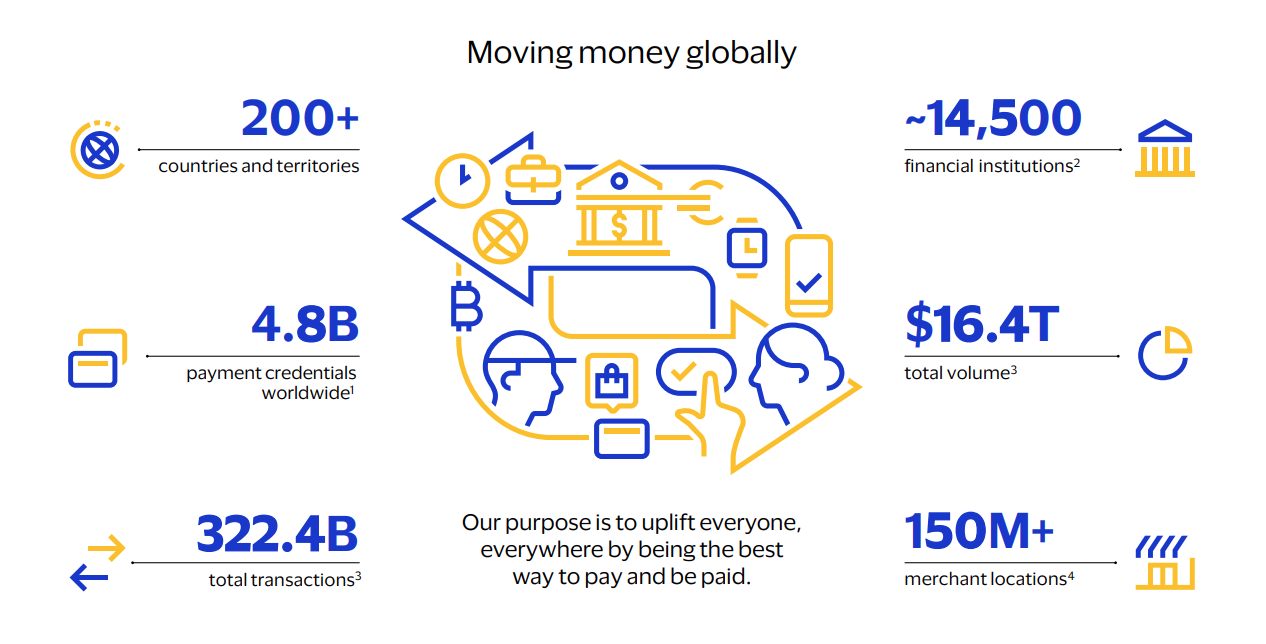

Network effects can also form a significant barrier for companies. Hohn (2025) mentions companies like Visa and Meta Platforms. As of June 30, 2025, TCI had invested over $6.7 billion in Visa, making it the third-largest holding in TCI's U.S. portfolio with a 13% weighting (Dataroma, 2025).

In a world increasingly shaped by AI, I expect that a moat based on network effects will be among the strongest—especially when reinforced by entrenched human behaviors (social network effects > procedural network effects).

Switching Costs

Within the realm of high switching costs, Hohn mentions “mission-critical software”. Once this type of software is installed, customers (businesses) are very reluctant to make changes due to the inherent complexity (Hohn, 2025).

Examples include enterprise software implemented by companies such as SAP and Salesforce. These are typically very robust systems in which companies are indeed hesitant to make modifications. To what extent could AI change this dynamic? For instance, if AI were able to execute a full migration to a new system in a relatively short period of time? Perhaps this is still some way off, but it is certainly worth considering.

What remains important for companies like SAP and Salesforce is that they embed AI into the services they provide, so that the consumer surplus they create remains as high as possible for as long as possible, reducing the likelihood of customers considering switching. That said, companies exploring enterprise software solutions may encounter new entrants with AI natively integrated at the core of their platforms, potentially resulting in highly competitive models for incumbents. As I have noted earlier, upfront time and investment costs in software services could become obsolete if AI advances to the point where it can replicate decades of accumulated investment in a very short timeframe. In my view, this is an important factor to bear in mind when evaluating SaaS companies that have built IP-based advantages through decades of R&D.

Ultimately, it comes down to problem-solving for companies that are active in the realm of SaaS, an area in which AI is rapidly improving. On this basis, value is created, and AI itself may increasingly contribute to that process. In such scenarios, enterprise software providers must position themselves as leaders in delivering the best AI tools to their clients.

Recurring Revenue

For Hohn, recurring revenue streams are important, though less in terms of the exact predictability of when they recur. What matters most is that the revenue is derived from essential products or services, rather than discretionary or optional spending.

An example Hohn (2025) highlights is credit rating agencies: firms that assess bonds and other debt instruments. Their clients (bond issuers) pay for these services, though refinancing timelines can vary. Ultimately, however, the service remains essential. In other words, we may not know exactly when companies like S&P Global and Moody’s will generate revenue, but we can be confident that it is very likely to occur, given the world’s ongoing reliance on the issuance of new debt securities.

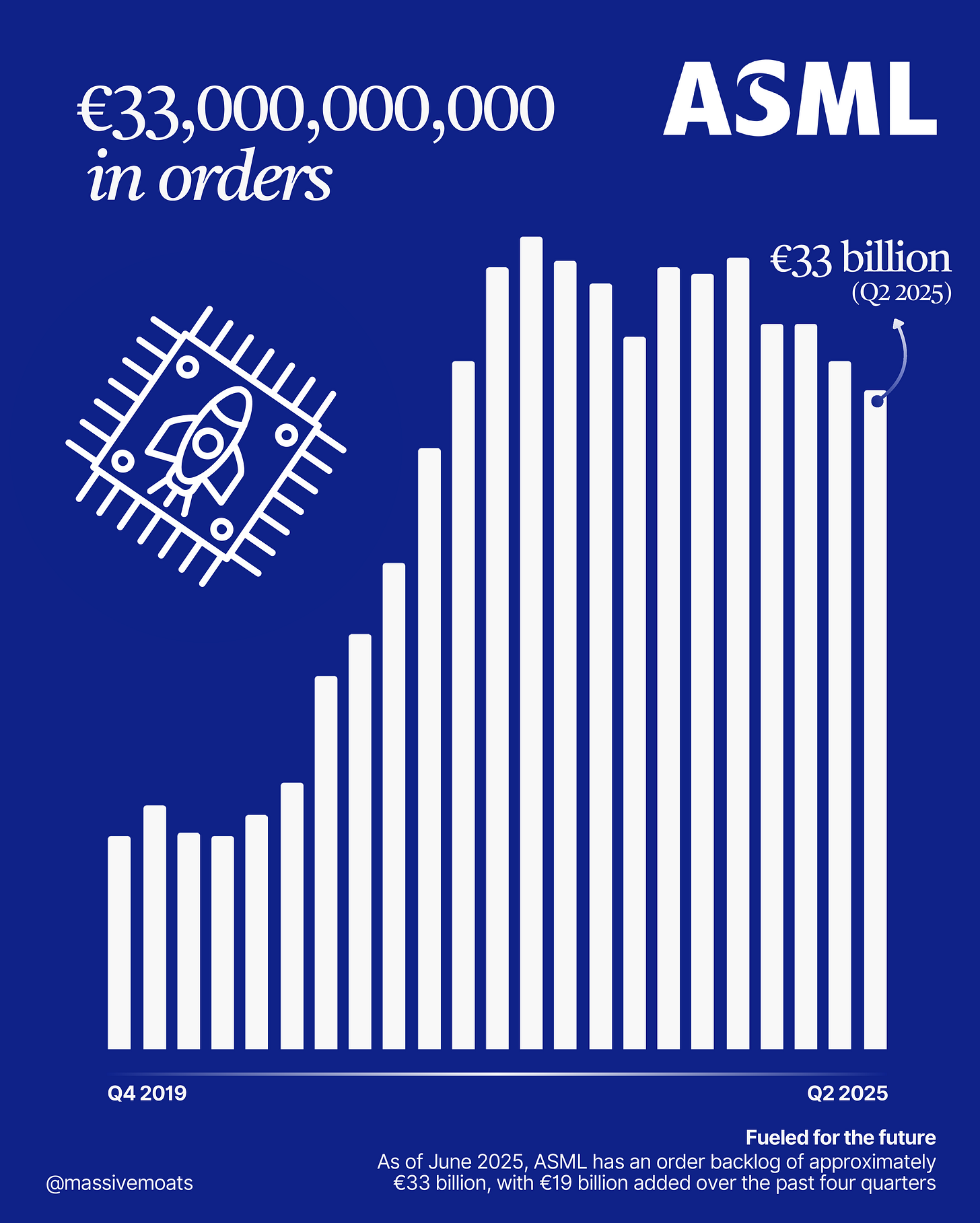

This strongly reminds me of ASML, which this year faced much debate over whether the company will grow in 2026. I question whether it makes sense to base an investment thesis on such short-term considerations. By 2050, we are unlikely to look back and focus on which precise year growth occurred during the late-2020s investment cycle. In my view, whether or not 2026 brings growth is irrelevant; what truly matters is the absolute value creation ASML can achieve over its lifetime.

Regulation

According to Hohn (2025), when a company has low barriers to entry, it is a negative factor, as competitors are likely to storm the company’s market through competition, disruption, or substitution.

Conversely, excessively high barriers to entry can invite regulatory scrutiny. Hohn therefore argues that a certain degree of competition is acceptable, provided it remains weak. A case in point is the aircraft engine industry, where a smaller player operates with a limited market share, offering products inferior to those of the market leader, according to Hohn (2025).

In such scenarios, the smaller competitor will attempt to compete on price, as the quality of its products cannot match that of the market leader. The market leader, in turn, will continue to focus on the quality of its products as well as the trust of its stakeholders. This is because that is where the potential for sustainable value creation lies, particularly in the market for suppliers to aircraft manufacturers.

Chapter 5. Valuation

This chapter focuses on the role of valuation in Chris Hohn's investment philosophy. How does Hohn approach the valuation of companies?

We don’t even look at that until we get comfortable that the barriers are so strong it will be around.

— Chris Hohn

(Source: NBIM, 2025)

Hohn indicates that the valuation question is secondary. This is also the approach I follow in my research process: I focus primarily on the qualitative aspects (how strong is the moat and its slope?) before turning my attention to the company’s valuation. After all, we must first assess the quality of a business before we can base a valuation on it.

The paradox is that the valuation of a company determines your ultimate return when you enter a position, as does the valuation at which you sell the position. The longer your time horizon, the more the IRR will shift from being influenced by the company's initial valuation to its intrinsic, value-creating forces. The latter is what will determine whether a company is a good long-term investment.

ⓘ Example Scenario

As an example, Hohn cites the company Moody's and its revenue growth over the past 100 years. According to Hohn (2025), it grew at a 10% CAGR over this period. If we ignore any potential increase in profitability, the following illustration shows the effect of a difference in valuation at the time of purchase:

A) You bought Moody's shares in 1925 at 45x earnings (P/E ratio: 45x).

B) You bought Moody's shares in 1925 at 15x earnings (P/E ratio: 15x).

As of September 2025, Moody's trades at a P/E ratio of 41x. With this information, your returns over the past 100 years would have been:

A) 9.90% CAGR (a minimal difference from the 10% CAGR due to minor multiple contraction).

B) 11.11% CAGR (a slight difference from the 10% CAGR driven by a multiple expansion).

You might ask yourself if you would have wanted to miss out on this ride up by waiting for Moody's to trade at a P/E ratio of 15x.

Of course, it is preferable to enter at the lowest possible valuation. If you had invested €1,000 in 1925 at both valuations, your final returns in 2025 would be, respectively:

A) €12.6 million (rounded)

B) €37.7 million (rounded)

One scenario offers an insane return (for such a long period), while the other would have yielded an even higher return. For the long-term investor, however, this matters less.

Perhaps you've already noticed, but the difference between €12.6 million and €37.7 million is a factor of three. This corresponds to the difference in P/E ratios: 15x versus 45x, which is also a factor of three.

Expressed in percentages, you would have achieved the following returns:

A) +1,259,900% (rounded)

B) +3,769,900% (rounded)

Here, scenario B is effectively about three times higher than scenario A. Thus, scenario B is actually 1,259,900% * 300%.

With a growth rate of 9.90% CAGR per year, you would have to wait approximately 12 additional years in scenario A to achieve the same result as scenario B. That is, ~112 years instead of 100 years for scenario B.

In other words, when a high-quality company trades at a high valuation, new investors must essentially pay a number of years' worth of "entry fee" to take a position. The amount of this goodwill payment depends on market sentiment and can, as with Moody's, range from a few years to a bit more, on a scale of 100 years.

Is the current P/E ratio of 41x high? Setting aside my view that a P/E ratio is meaningless in isolation, in this fictional scenario, it could prove to be a perfectly fine entry point in the long run if Moody's continues to grow at a 10% CAGR for the next 100 years.

In my view, as investors we should focus exclusively on the company itself, rather than attempting to predict the irrationalities of other market participants. After all, we simply do not know whether Moody’s will ever again be available at a lower valuation. In theory, the company could continue to trade indefinitely at relatively high multiples (read: fairly valued, but with several years of entry fee priced in as a premium). If that multiple were to briefly compress to a very low level, it would be more a matter of luck than something we could have anticipated in advance. To what extent should we even want to time this? And if the valuation does decline, at what point should we enter? At 35x, 30x, or 25x earnings? And when does the rerating begin again? We simply do not know. The only sensible approach is to act on the information available from the present and the past, and on our discounted expectations for the future.

That said, if Moody’s were to fall overnight from a multiple of 45x earnings to 15x earnings, an investor would be facing a short-term mark-to-market loss of –67%. In the short run, buying at seemingly elevated valuations can be painful when multiple compression has a greater (negative) impact than the (positive) change in intrinsic value. In the short term, it is always the former that dominates returns. Over the long term, however, it is the latter that will drive the vast majority.

Personally, I try to treat sharp multiple compression in the short term as an opportunity: ideally, I would experience as much short-term pain as possible, enabling me to add to my position at a lower valuation and thereby enhance my long-term returns.

Regarding valuation methodologies, Hohn (2025) notes that TCI takes a long-term approach, in part through the use of DCF models (discounted cash flow). He also states that the level of a valuation multiple at the time of purchase matters less when viewed over a longer time horizon.

When to sell?

The question of when to exit a stock is perhaps one of the most difficult for investors. I personally do not see the decision of exciting a position as a single moment in time, but rather as a long process, with both the lead-up to the eventual sale and the period that follows. Throughout this process, various biases can arise, of which we as investors must remain aware.

Hohn sells a stock when his view of the company’s intrinsic value is no longer favorable, including in comparison with other investment opportunities. This assessment takes into account not only valuation but also conviction. The price of a stock should be at or below its intrinsic value, according to Hohn. He agrees that intrinsic value is not a single objective figure. Questions about which years will see which growth rates cannot be answered with certainty, since the future is inherently unpredictable. Valuation, therefore, is merely an approximation.

It is crucial that we stay focused on qualitative aspects in the realm of valuation, guided by questions such as: ‘Will the company still exist in 10, 20, or even 30 years?’ and ‘Will there still be demand for its products and/or services?’

This makes it more meaningful for investors to concentrate on the small group of companies whose prospects can be assessed with greater confidence. According to Hohn, these are also the most powerful companies.

I share Hohn’s perspective on the topic of valuation. The intrinsic value investors assign to a stock derives from a combination of factors, with the assessment of the company’s quality and the discounting of future prospects being among the most important.

Chapter 6. Concentration & Sectors

6.1 Concentration

Hohn stated in 2013 that by focusing on a few strong ideas, concentration can be converted into alpha. At the Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM) Investment Conference in 2025, Hohn referenced George Soros: “It's not whether you're right or wrong, but how much money you make when you're right and how much you lose when you're wrong.”

Hohn notes that it makes little difference to a total portfolio if an investor with a 1% position is proven to be very right. Positions of 10%, 15%, or even the 25% that TCI has held in the past, do make a significant difference, Hohn argues. However, this is a double-edged sword: you profit immensely when you're right, but when you're wrong, it will have a noticeable impact on the total return.

According to Hohn, concentration is important because there aren't hundreds of good ideas or companies.

Is high concentration risky?

Hohn acknowledges that a highly concentrated portfolio does come with risks, but these risks must be viewed within a broader spectrum and weighed against the advantages that investors gain with a concentrated approach. Hohn refers to Warren Buffett, who said: “Risk comes from not knowing what you're doing” (2025).

Concentration, in effect, creates a tension between different types of risks, which investors must be well aware of and manage in a way that aligns with their own strategy and perception of risk.

This is a personal trade-off for everyone. Regarding concentration, I share a similar view to Hohn, limiting myself exclusively to the best ideas by giving them high exposure through high concentration.

I don't use, however, a rigid framework where a fixed percentage weighting is derived from various factors. The current weightings of the companies in my portfolio are, like Hohn, driven by conviction, a combination of valuation, future outlook, and my assessment of the company's moat, with the latter two always having to meet strict quality criteria.

A story is just a story. You have to focus on what matters. [...] You need to get out of the noise and just focus on the handful of things that matter.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

6.2 Sectors

Hohn (2025) deliberately avoids investing in certain sectors with his TCI fund. He refers to these as “risky” and “bad” industries. According to Hohn, there are only around 200 companies worldwide that he considers both high-quality and investable.

Most industries are bad industries.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

Hohn notes that he used to invest in these sectors in the past, but has since learned from that experience. Below is an overview of the sectors that Hohn generally excludes upfront (2025), along with my own perspective on these sectors.

Banks

Hohn essentially excludes the banking sector initially. This is due to the opacity of bank balance sheets, which often include high leverage, and the generally low quality of most banks’ earnings.

Banks are inherently difficult to analyse, opaque, highly levered and speculative—we don’t want speculations, we want investments.

— Chris Hohn (Source: The Financial Times, 2012)

Hohn also highlights the risk that, sooner or later, a leader may be appointed without a lot of intelligence and who lacks the capability to make sound capital allocation decisions.

I agree with Hohn that banks are opaque institutions. I expect that many investors holding bank stocks have little understanding of how the underlying financial processes of such institutions actually operate and are reflected in their financial statements. Similarly, there is a real risk that one day a leader may take office who lacks the necessary expertise to run the institution effectively. I would hesitate to describe this as lower intelligence, but rather as a higher degree of ignorance; being unaware of his lack of knowledge.

Automotive

Hohn argues that the automotive industry is clearly a commodity sector.

I partly agree with this view: most car manufacturers compete for the same customers, typically on price in the lower- and mid-tier segments of the automotive industry, or through a combination of price and brand experience in the mid- to high-end segments.

The nuance I would add is that within the upper tail of the high-end automotive market, there are companies that are genuinely high-quality. Take Ferrari, for example, which possesses a form of pricing power that it can leverage to create future shareholder value. This through its limited production, brand strength, and cultivated status. One could justifiably argue that Ferrari is less of an automotive company and more of a luxury company.

Retail

Hohn also states that the retail sector is one he prefers to avoid.

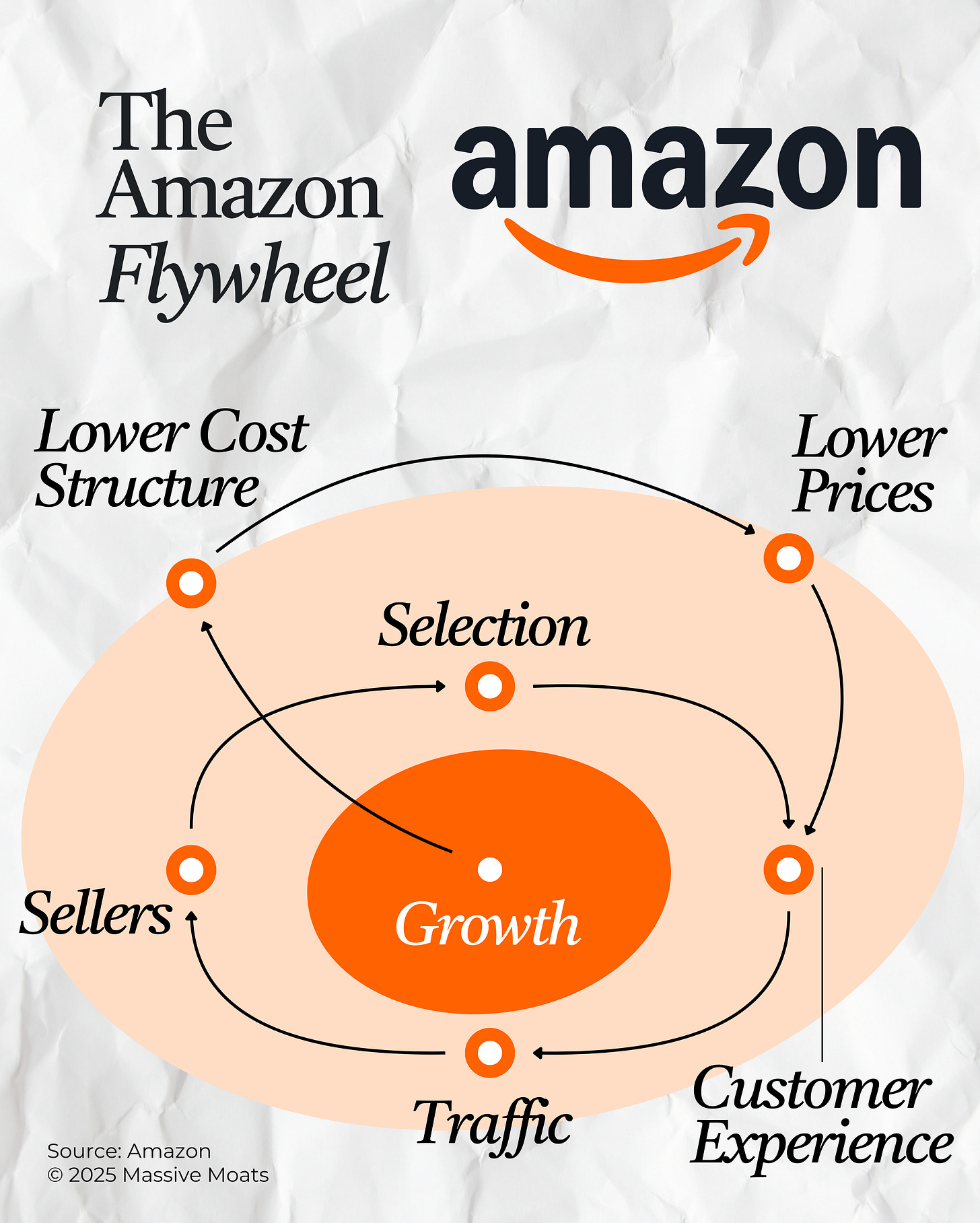

I share the view that the vast majority of retail businesses can initially be excluded. Nonetheless, I believe there are certain companies that have established a strong proposition. For example, Costco Wholesale has built a flywheel of customer loyalty and scale. Similarly, a company like Action (one of the holdings of 3i Group) exhibits characteristics in its business model and operations that, in my view, create a unique proposition through existing scale advantages. I would also not initially exclude a company like Amazon (Retail) from my investment universe.

It is possible that Hohn may be referring to traditional retail companies. In that case, the companies mentioned above could potentially fall within Hohn’s investment universe, even though there is no evidence of this in TCI’s current portfolio or in the fund’s transactions over the past few years.

Insurance

Like Hohn, my primary focus is not on companies in the insurance sector. With the knowledge I currently have about this industry, I find it challenging to envision a robust, future scenario of an insurer which entails long-term, sustainable value creation in an era of increasing technological change.

At present, there are undoubtedly insurance companies that focus on a niche within their market and achieve high returns on the premiums they collect. However, the question remains to what extent this value creation will remain high in the future when AI creates opportunities for disruption and substitution.

Hohn also lists sectors and industries such as commodities, commodity manufacturing, tobacco, traditional asset managers, fossil fuel utilities, airlines, wireless telecom, media, and advertising agencies. “It’s a very long list. Why? Because it’s competitive.”, according to Hohn (2025).

In other words: focus on companies that are expected to withstand future (technological) changes and may even benefit from them through higher productivity and a lower cost base.

[...] there are 200 companies that we consider to be high-quality and investable.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

According to Hohn, there are only 200 companies worldwide that he considers high-quality and investable. Yet, he invests in just over 10 of them. The following chapter provides an overview of which companies these are and what they do.

Chapter 7. TCI’s Portfolio Breakdown

This chapter focuses on TCI’s portfolio. TCI does not publish public investor letters or periodic overviews of its current holdings. Nevertheless, based on publicly available sources, we can reconstruct a portfolio.

For investments listed in the United States, we can refer to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Because TCI Fund Management Ltd. manages more than $100 million in U.S. listed securities, it is legally required to file a Form 13F with the SEC every quarter.

Companies listed exclusively on non-U.S. exchanges (for example, in Europe or Asia) generally do not appear in these filings, as Form 13F only requires disclosure of securities listed in the United States.

According to the most recent filing (for the quarter ending June 30, 2025), TCI reported 10 U.S.-listed securities with a total value of approximately $50.7 billion (sec.gov, 2025), namely:

GE Aerospace (GE): $12.2 billion;

Microsoft Corp. (MSFT): $8.7 billion;

Visa Inc. (V): $6.8 billion;

Moody’s Corp. (MCO): $6.6 billion;

S&P Global Inc. (SPGI): $5.8 billion;

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC): $4.2 billion;

Alphabet Inc. (GOOG + GOOGL): $2.9 billion;

Canadian National Railway Co. (CNI): $2.4 billion;

Ferrovial SE (FER): $1.0 billion.

Based on publications regarding significant shareholders of companies, we can also add the following European companies to TCI’s portfolio:

Safran SA (France);

Airbus SE (France);

Cellnex Telecom SA (Spain);

Aena S.M.E., S.A. (Spain).

Below is an overview of these companies.

GE Aerospace ($GE)

As of June 30, 2025, GE Aerospace was TCI’s largest position. GE Aerospace is the aviation division of the U.S. industrial conglomerate General Electric, which between 2021 and 2024 was split into three segments: a healthcare division (GE HealthCare), a group of energy companies (GE Vernova), and the aviation division, GE Aerospace (formerly GE Aviation).

GE Aerospace develops and manufactures aircraft engines, systems, and components for both commercial and military aircraft worldwide. In addition to engines, the company provides maintenance services.

The company also operates a 50/50 joint venture with the French company Safran, known as CFM International.

Microsoft Corp. ($MSFT)

According to Dataroma (2025), TCI entered Microsoft in Q4 2017 and gradually expanded the position through various purchases, as well as a few partial sales, to reach a stake of $8.7 billion by Q2 2025.

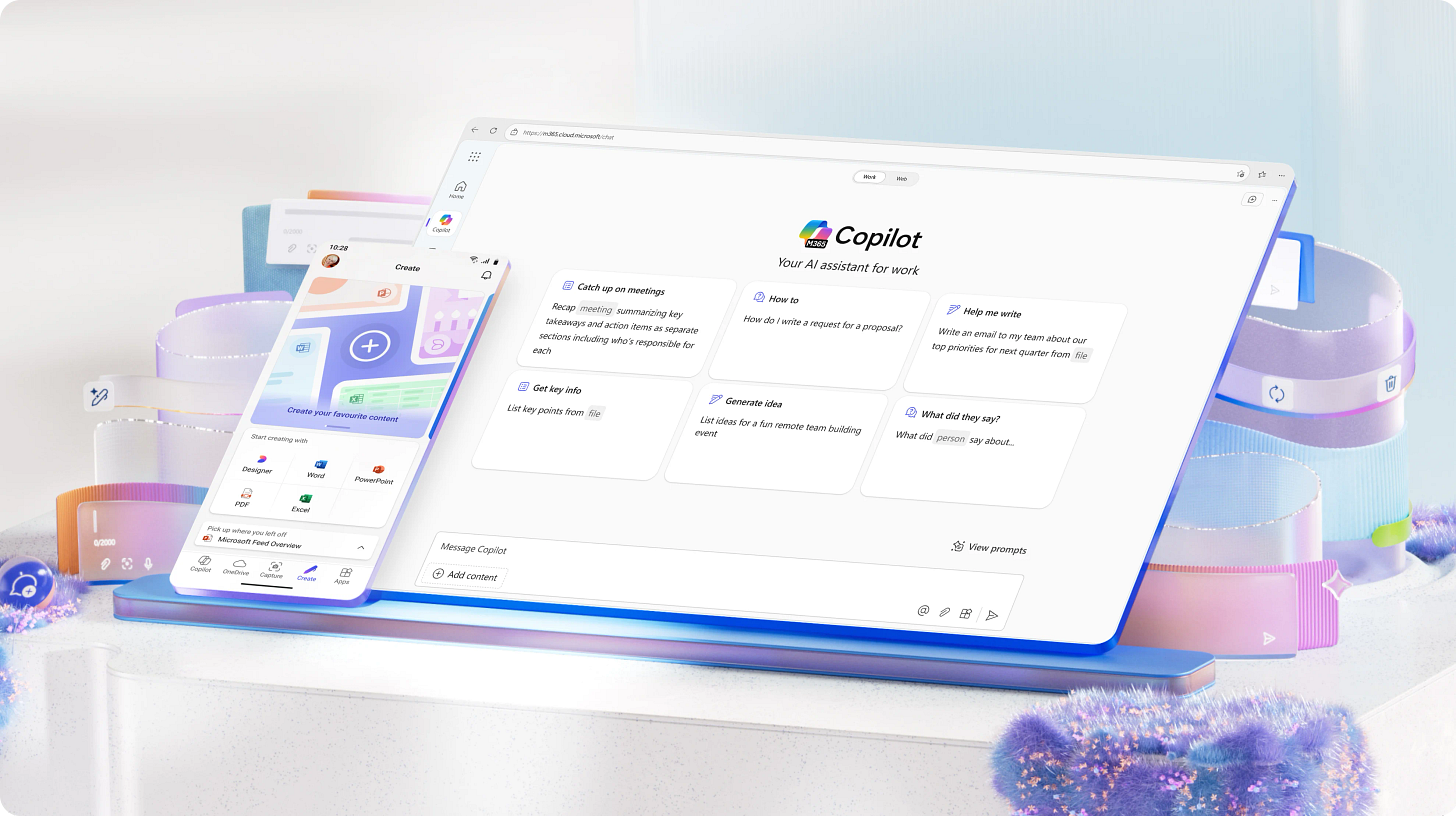

Hohn (2025) notes that Microsoft benefits from bundling (of software services) as well as the switching costs this entails. For example, Microsoft Teams, despite being adopted later by the public than Zoom, was able to outperform Zoom.

Microsoft won that battle because they had the installed base, the incumbency [...] and high switching costs, because once people are using their office software they don’t want to switch.

— Chris Hohn (Source: NBIM, 2025)

Hohn also points out that a product does not necessarily need to be the best in its category, as long as it is ‘free’ and/or available within an ecosystem of other services.

In my view, Microsoft will continue to benefit in the coming years from the brand strength and trust it has built over decades. Ultimately, customer loyalty is largely driven by trust when it comes to storing important data. For many users, Microsoft as a partner provides that sense of security. Combined with the consumer surplus accumulated over time, this forms a powerful barrier of goodwill. Nevertheless, there are risks for Microsoft. Below are some of my considerations.

I do not rule out the possibility that Microsoft’s dominance may erode in the future if alternative services create significantly higher value for users and traditional switching costs are diminished by AI. It is possible that AI systems will emerge as the foundation for a new internet, potentially operating independently of traditional software providers. This could reduce switching costs for consumers, while offering software services in a more holistic, AI-driven manner.

Additionally, I foresee increasing integration between front-end portals (e.g., browsers, apps, LLMs) and software suites. With an AI-driven system, full integration will enable seamless data retrieval and processing across internal and external systems. If a company like Alphabet executes this perfectly, it could potentially increase the market share of its software programs within Google Workspace.

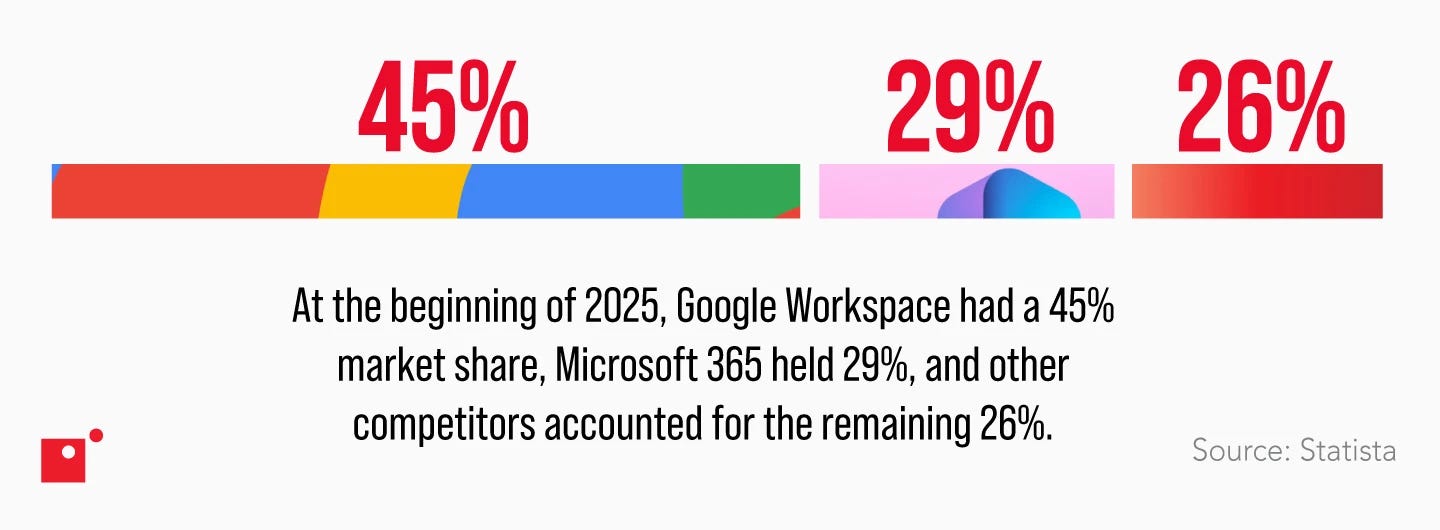

Returning to Hohn’s comment about offering office software for free: Google Workspace already has a strong position in this regard. According to Statista, Google Workspace had a market share of 45%, compared to Microsoft 365’s 29%.

Particularly if Google’s underlying AI technology surpasses Microsoft’s over time, Google could gain further ground with its already well adopted browser Google Chrome, and search engine Google. That said, the opportunity for Alphabet to commercialize this is also increasing. In my view, Alphabet has barely tapped into these opportunities to date, representing a huge potential for future intrinsic value creation.

Visa Inc. ($V)

With a position of $6.8 billion, Visa is also among Hohn’s favored companies worldwide. In Q2 2025, TCI increased its stake in the payments network provider by 14.6%, which, along with additional purchases in S&P Global, was the only notable expansion during the past quarter.