Moats: An Introduction to the Drivers of Value Creation

What Bessembinder, Mauboussin & Callahan, and Buffett teach us about the few companies that outperform over the long term

Foreword

As investors, why should we focus on companies possessing a moat? In this article, I aim to address this question while introducing this concept, a term conceptualized by Warren Buffett. As always, the information shared in this article should not be construed as financial advice. Please refer to the full disclaimer on the website.

Our Objective as Investors

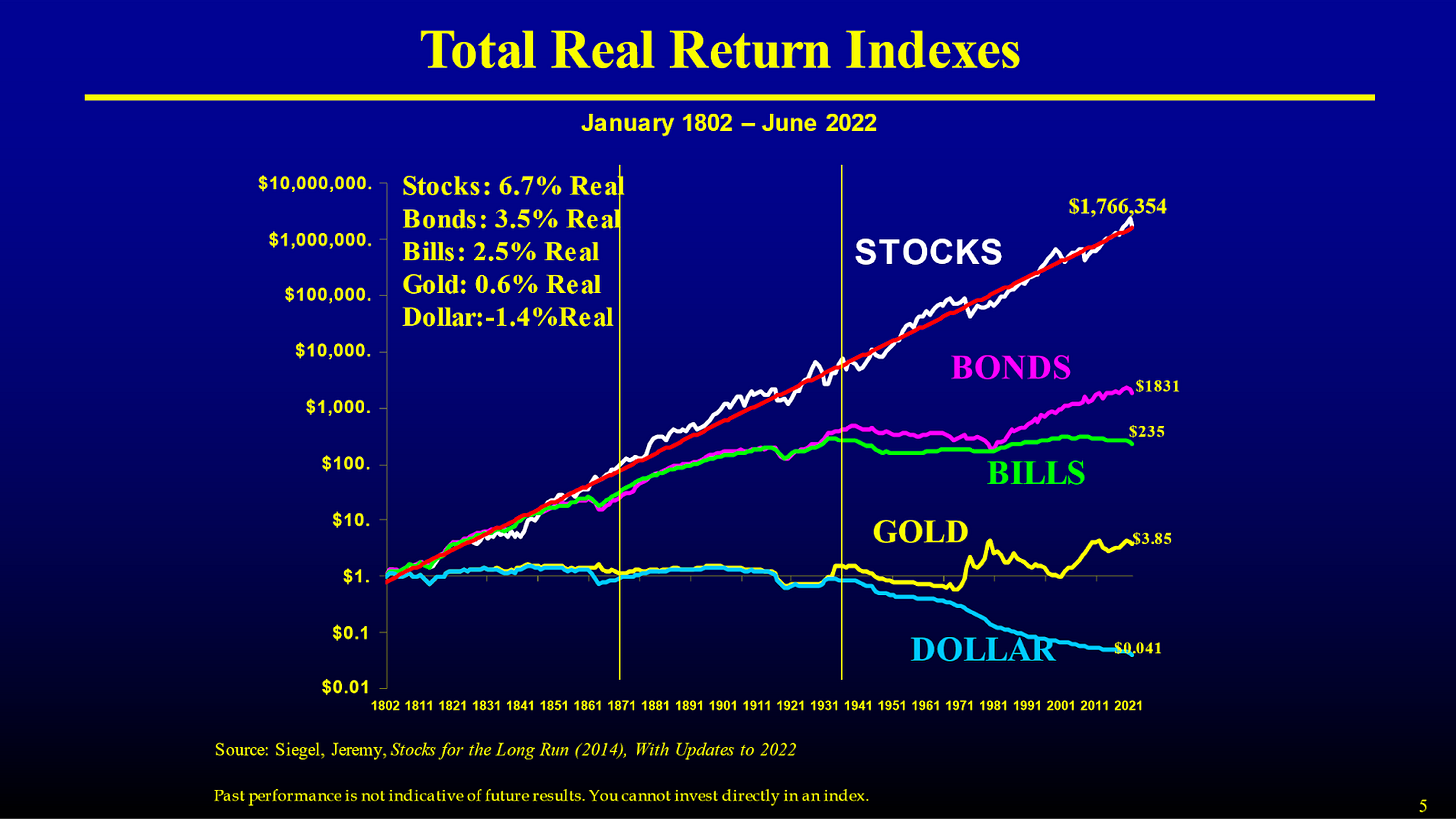

Before delving into the concept of moats, it's beneficial to briefly consider our overarching objective as investors. In my view, our long-term goal as investors is to enhance our purchasing power. In other words, we aim to achieve a growth in our invested capital that outpaces the depreciation of currency over time. Successfully achieving this creates net value at an individual level, signifying an increase in our wealth's purchasing power.

There are multiple pathways to achieve this. From my perspective, building equity in companies represents the most compelling method for generating long-term growth in purchasing power. Jeremy Siegel's well-known publication, Stocks for the Long Run, demonstrates that equities have historically been the superior asset class over an extended period. Specifically, from January 1802 to June 2022, stocks delivered a real compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.7% as Total Shareholder Return (TSR). The term "real" here signifies that this percentage has already been adjusted for inflation, meaning the 6.7% CAGR reflects the net return, or the increase in purchasing power.

This represents a significant outperformance compared to bonds and bills, as well as the price evolution of gold. While these asset classes may appear to be effective inflation hedges based on historical data, the creation of purchasing power fundamentally stems from companies. It is companies that are able to at least raise the prices of their products and/or services in line with the inflation of their variable and fixed costs that can create long-term value.

These companies are subsequently responsible for the value creation evident in global market indices and the ETFs derived from them. Without the presence of these value-creating entities, there would be no increase in purchasing power for us as holders of these ETFs.

Research by H. Bessembinder (2018)

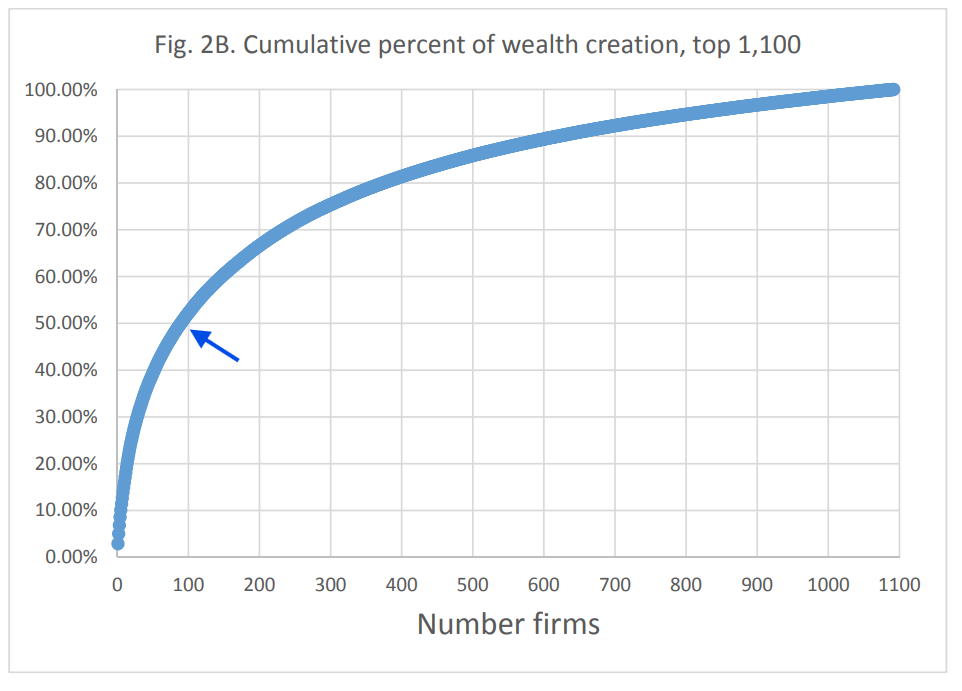

Upon closer examination of how this value creation materializes, it becomes clear that only a small cohort of companies is responsible for the net wealth creation in the financial markets.

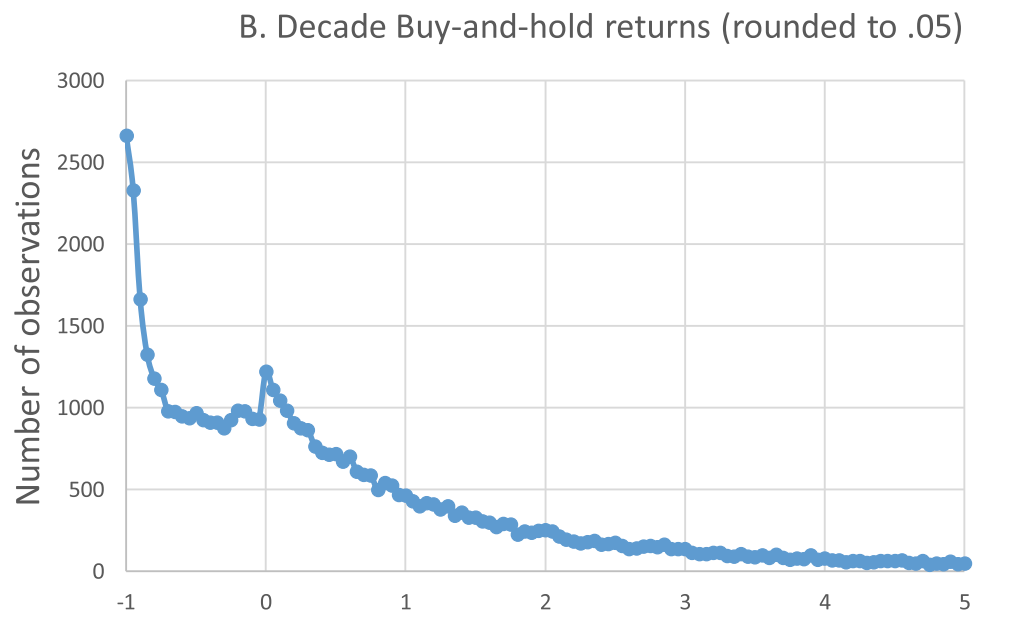

In his paper, "Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?", H. Bessembinder (2018) shared findings from his research into the genesis of TSR for U.S. companies. Over the period from 1926 to 2016, a mere 42.6% of companies (n = 25,967) managed to generate returns exceeding those of 1-month Treasury bills (this research includes considerations for delistings and incorporates dividends). Stated differently, 57.4% of companies yielded returns lower than that of 1-month Treasury bills.

The top 1,092 performing companies in terms of TSR (representing 4.3% of the total 25,332 companies in this sample) accounted for the ultimate net value creation for shareholders (i.e., the alpha relative to the return on 1-month Treasury bills). The remaining 95.8% exhibited, over their lifespans, a collective return equivalent to that of 1-month Treasury bills. From this data, we can distill the highly positive asymmetry of the stock market: while companies can decline by a maximum of 100%—the most common outcome Bessembinder observed, rounded to a 5-percentage-point frequency (see figure below)—they theoretically possess infinite growth potential.

Based on these findings, and numerous other lessons from financial market history that underscore this highly positive asymmetry, investors can pursue two distinct approaches to potentially benefit from this in the future as well.

ETF’s

Firstly, with minimal knowledge and time commitment, you can leverage the value creation of the most successful companies by tracking market indices. Today, the market for investing allows for accessible equity exposure with relatively small capital. The methodologies of indices such as the S&P 500 and NASDAQ-100 provide the opportunity to gain exposure to mechanisms of wealth creation. By selecting a fair provider that offers ETFs tracking these indices, you can build wealth with minimal involvement. Historically, this strategy has proven to outperform inflation, thereby increasing the purchasing power of those who invested capital for the long run.

Should future market dynamics mirror those highlighted in Bessembinder's research, this increase in purchasing power will primarily be driven by a limited number of companies. A significant proportion of the remaining companies will collectively yield returns equivalent to 1-month Treasury bills. ETF investors consciously choose this path, rather than individual stock selection, to indirectly capture both the significant winners and the numerous underperformers within their portfolios through ETF investments.

I personally invest monthly in an ETF that tracks the NASDAQ-100 Index. In late 2024, I conducted extensive research into the world of ETFs, which I've compiled into an e-book (in Dutch). This e-book is available for complimentary download on our Dutch website; beursbaas.com.

The positive performance of the overall market is attributable to large returns generated by relatively few stocks. — Bessembinder (2018)

Individual Stock Selection

Bessembinder's research revealed that the top 90 performing companies (less than 0.33% of the total) were responsible for 50% of the aggregate shareholder wealth creation, as illustrated in the figure below.

This finding naturally sparks interest among many to identify some of these exceptional businesses for the coming decades. However, these statistics simultaneously highlight that the probability of randomly selecting one or more of these top-performing firms is exceedingly low. Fortunately, investors can apply stringent criteria to improve these odds.

For instance, I've established my own quality standards that companies must meet (e.g., growth, profitability, liquidity, ROIC, and capital allocation track record). This allows for the initial disqualification of a significant portion of companies. Ultimately, individual stock selection is a process of deduction. From the remaining pool of companies, investors can then 'fish' in their own fishing pond, merely focusing on high-quality businesses.

I've narrowed this down to 0.1% of the approximately 70,000 global publicly traded companies, forming an investable universe of roughly 70 companies. This selection is based on a combination of qualitative and quantitative criteria, all centered around the concept of moats—the drivers of value creation.

Value Creation

Companies generate value when the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) on their investments exceeds their cost of capital. This cost of capital, representing the blend of equity and debt funding these investments, can be derived from the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). Therefore, a strong indicator of value creation is:

Value Creation = ROIC > WACC

Conversely:

Value Destruction = ROIC < WACC

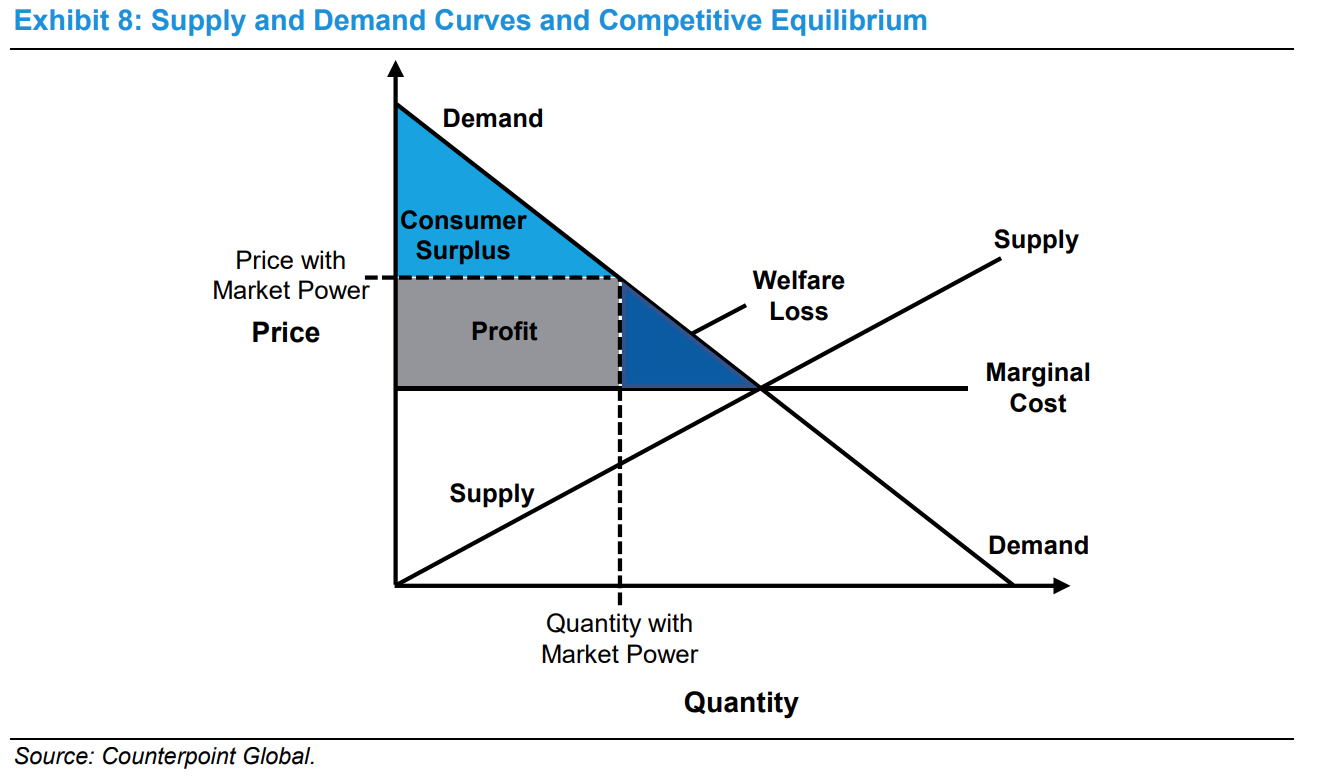

A company's value creation for its shareholders is a byproduct of the value it delivers to its customers. This occurs at the intersection of consumer surplus within the supply and demand framework, as depicted in the figure above. If companies fail to provide added value for which customers are willing to pay, generating returns becomes impossible. Every transaction in an economy inherently involves a consumer surplus, where customers acquire a product or service whose perceived utility value surpasses the price they pay. Companies then create value for themselves (and, by extension, their shareholders) when they sell products or services at a price above their cost.

As investors, we are thus interested in companies that not only create value for society and their customers but are also capable of capturing a portion of that value for themselves. Crucially, this capability should extend beyond a single, brief period and persist over the long term. In essence, investors should focus on companies that are expected to consistently create value for their customers and capture a share of that value into the foreseeable future.

Absolute Value Creation

When selecting companies, it's crucial to differentiate based on the following three factors:

The delta between ROIC and WACC, and its slope;

The duration over which a company is expected to sustain or increase this delta—the longevity of its competitive advantage;

The magnitude of invested capital and the potential for future investment opportunities—the scale at which a company can deploy capital at this favorable delta.

In formulaic terms:

Absolute Value Creation = (ROIC-WACC) x Longevity x Magnitude

While a company currently exhibiting a high ROIC and a significant delta relative to its WACC is a result of past investments, this can serve as an indication for future performance. However, for sustained future value creation, it's essential that a company can maintain its return on invested capital. Furthermore, an expansion of its scale, by capitalizing on secular trends, acts as an additional catalyst for value creation.

Therefore, for companies to sustain an above-average ROIC over the long term, they must operate in a manner that differentiates them from competitors. This requires possessing a competitive advantage—a moat.

Be Selective and Differentiate Among Companies

As demonstrated by Bessembinder's (2018) research, many companies historically have failed to deliver shareholder returns (TSR) that outpaced inflation. Given that a company's stock price, and consequently shareholder capital gains, tends to track its intrinsic value per share over the long term, it is paramount to identify companies capable of increasing their intrinsic value per share.

To enhance intrinsic value per share, companies inherently need to create value at the operational level. This means generating a return on invested capital that exceeds the cost of that capital.

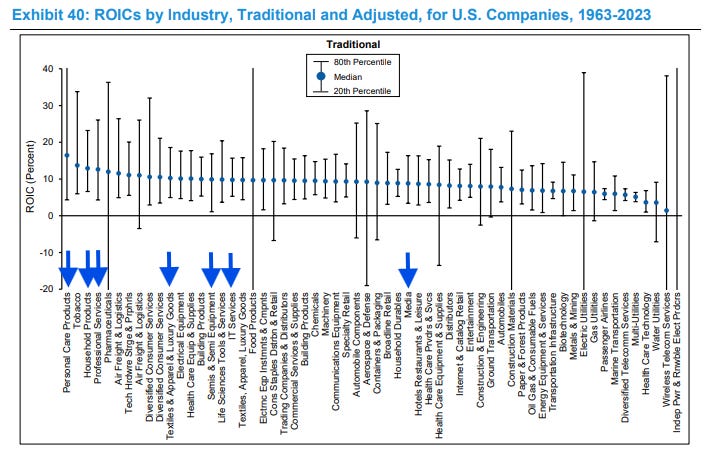

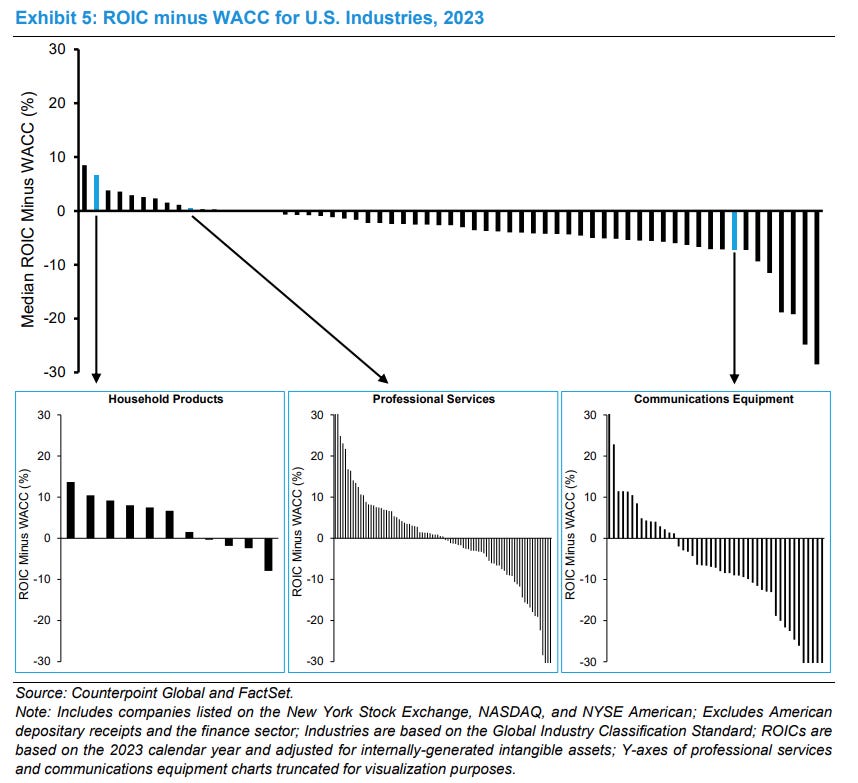

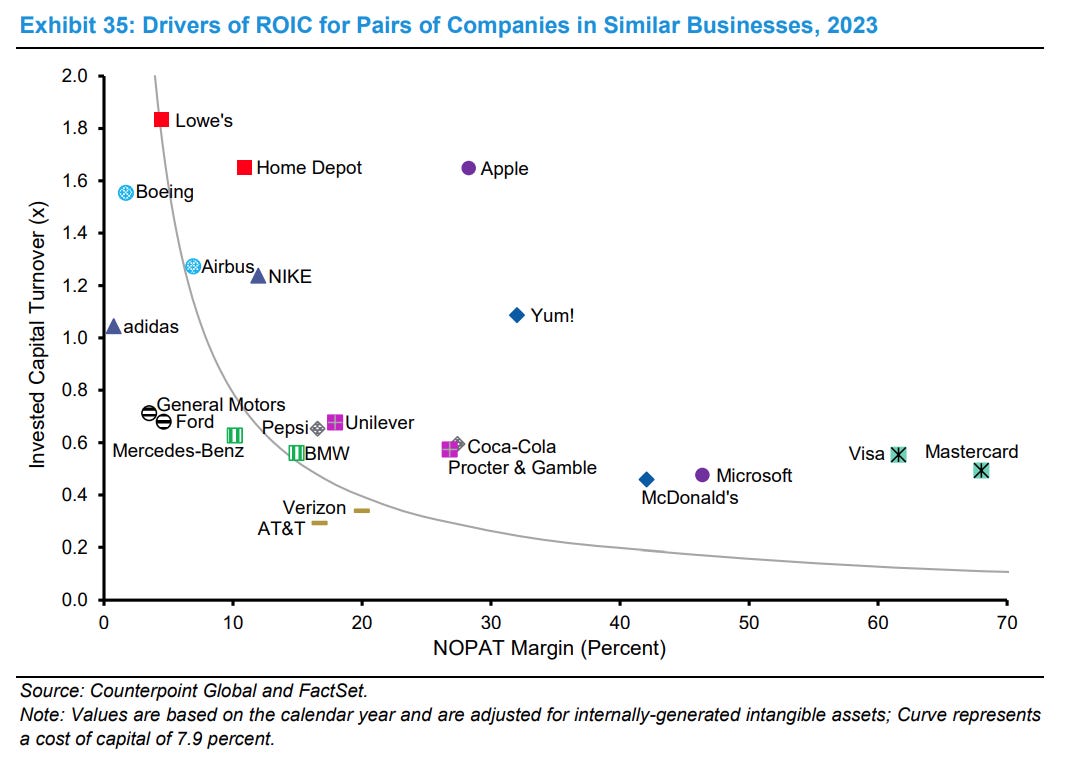

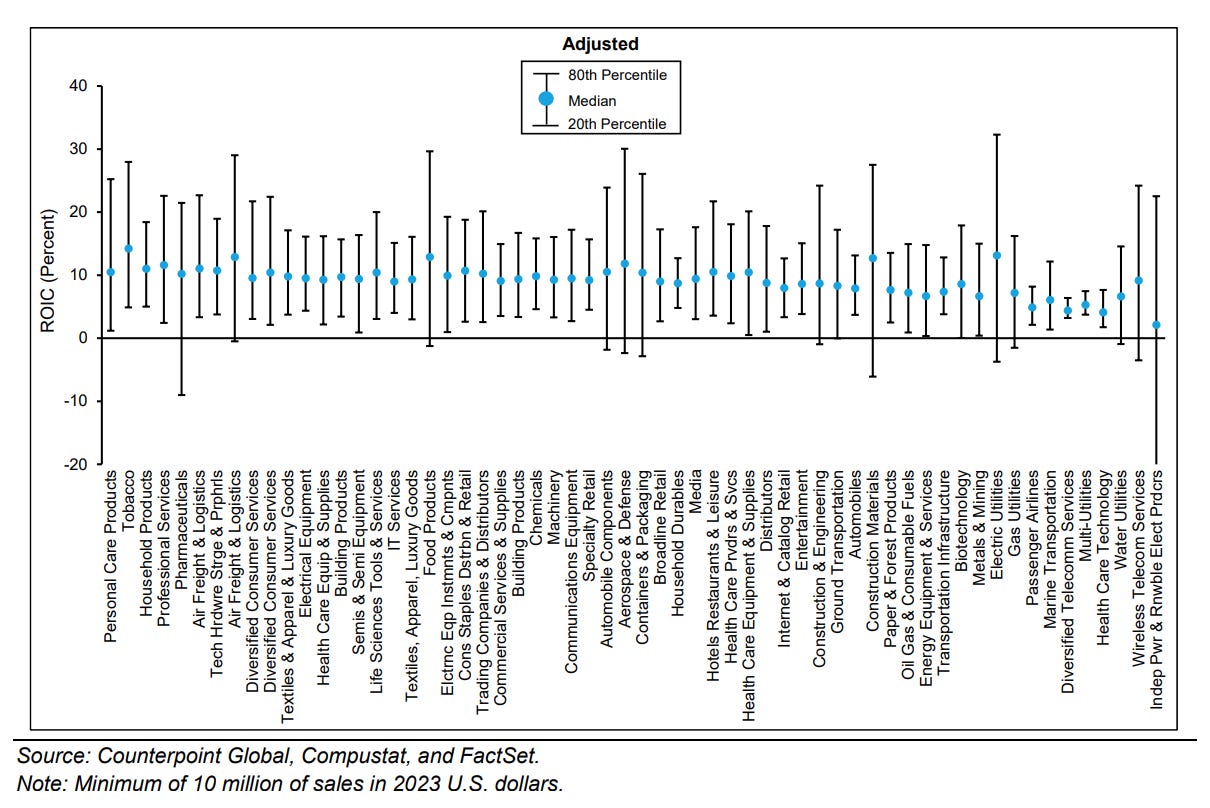

The delta between ROIC and WACC provides a robust indication of a company's value creation capability. As evident from the figure below, derived from Mauboussin & Callahan's (2024) research, many sectors exhibited a negative median ROIC-WACC delta in 2023. Only a limited number of sectors achieved a positive median delta.

It's crucial to note that within a sector seemingly experiencing significant value destruction, there can still be a number of companies exhibiting a high degree of value creation. In other words, even in a sector with a net negative delta between its average ROIC and WACC, individual companies can indeed be creating value. Conversely, the same holds true: a sector with a net positive delta between its average ROIC and WACC can contain companies that are destroying value.

So, what enables certain companies to successfully create value while others completely fail? Based on various studies, including Mauboussin & Callahan (2024), this, in my view, is fundamentally linked to the presence of a strong economic moat. A robust moat protects the positive delta between ROIC and WACC. This effect is further amplified when management pursues strategies focused on capturing and defending future growth trajectories driven by secular trends, all while continuously working to safeguard or expand their existing moat.

Genesis of Value Creation on the Business Level

A competitive advantage emerges when companies have cultivated something unique. This advantage allows companies to persistently exploit higher margins and ROIC than their industry peers.

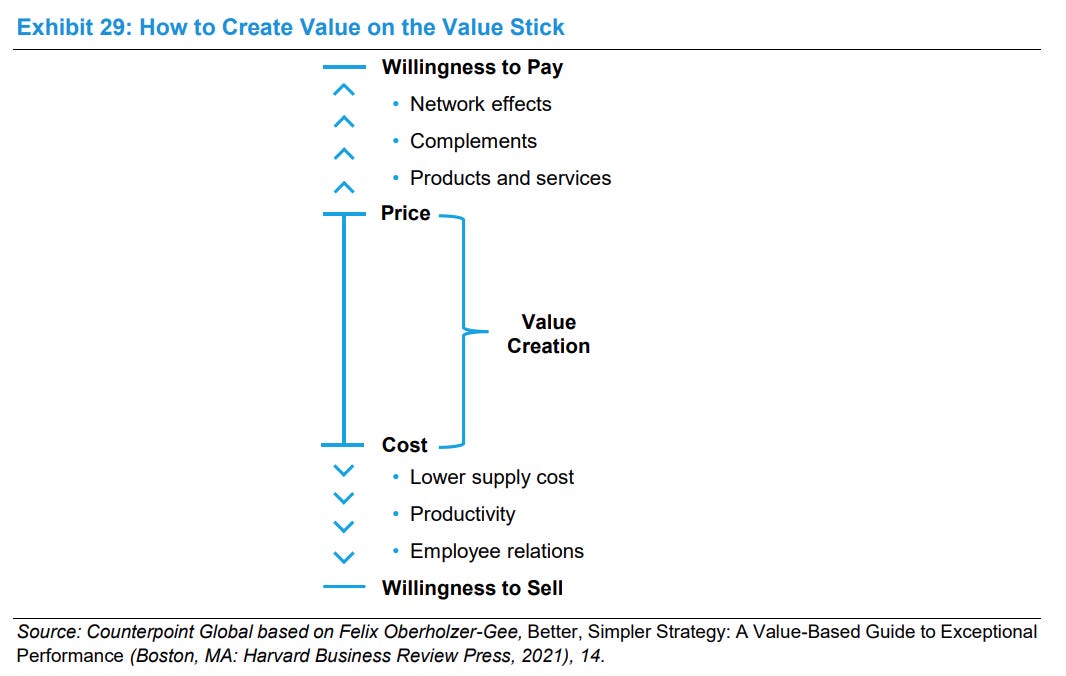

The figure below illustrates the genesis of value creation for a company and its shareholders. This value creation occurs when a company maintains a positive delta between its revenue and the total cost of that revenue. A moat serves as a bulwark against all forces seeking to erode this value creation, whether from vertical pressures on pricing (customers) or costs (suppliers), or from horizontal competitive influences.

It's not solely about the ROIC percentage as a driver of value creation, but rather the absolute ROIC measured in absolute terms. This is because, as we have established earlier:

Absolute Value Creation = (ROIC-WACC) x Longevity x Magnitude

A moat subsequently ensures:

The delta between ROIC and WACC can be higher than that of competitors, thus fostering value creation.

It provides a robust foundation for the company to continue benefiting from this delta in the near future, provided management consistently works to protect its moat.

When management also capitalizes on secular trends to further expand the company's moat, opportunities are created to increase the company's scale, its investment opportunities, and thereby its potential for future value creation.

This demonstrates that a moat offers a higher potential for value creation for a company, compared to industry peers lacking such competitive advantages. In essence, it is about absolute value creation (i.e., ROIC x invested capital turnover).

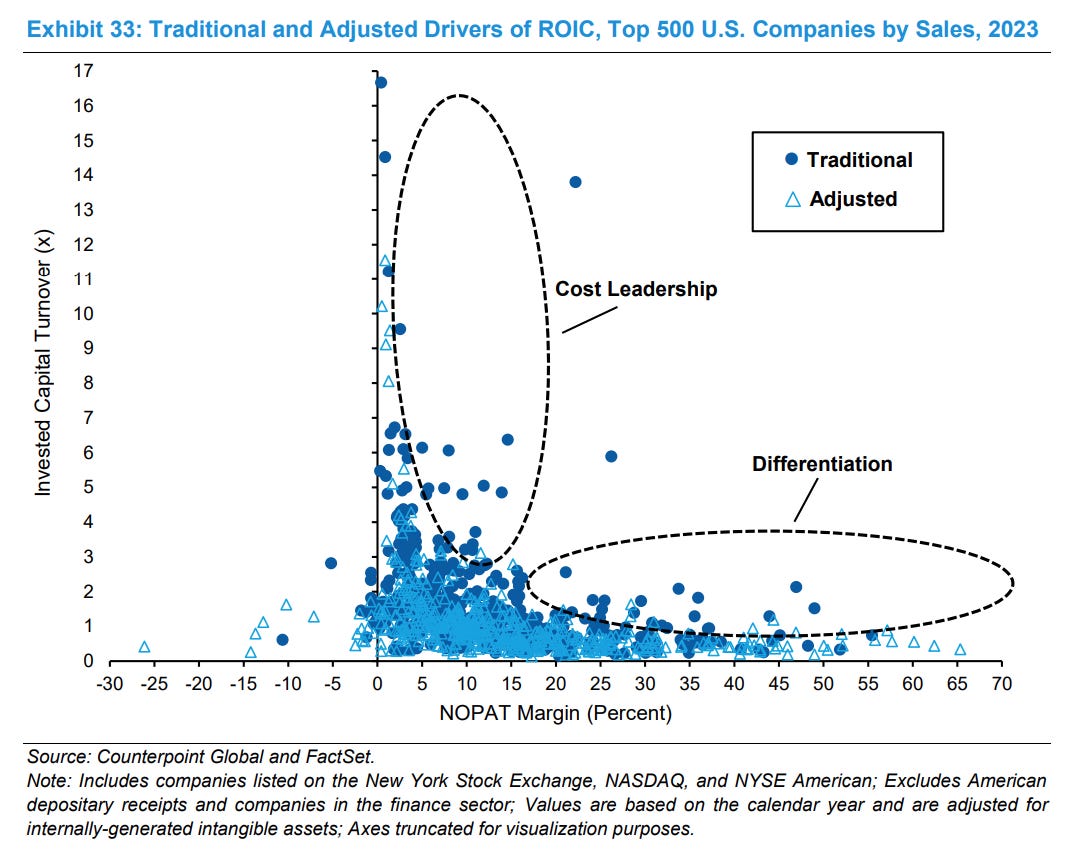

Companies can achieve value creation through either a high invested capital turnover with relatively low profit margins (cost leadership, e.g., Costco, Amazon, and Action), or a relatively low invested capital turnover coupled with high profit margins (differentiation, e.g., asset-light business models like Mastercard and Visa).

Therefore, as investors, we should be interested in companies capable of sustaining their value creation into the future. In essence, we seek companies with a durable competitive advantage.

As Warren Buffett noted, this is a crucial insight:

A truly great business must have an enduring “moat” that protects excellent returns on invested capital. The dynamics of capitalism guarantee that competitors will repeatedly assault any business “castle” that is earning high returns. — Warren Buffett

In the following article, I have compiled a concise collection of invaluable lessons derived from the extensive wisdom of Warren Buffett.

A tribute to Warren Buffett

On May 3, 2025, during Berkshire Hathaway’s annual general shareholders’ meeting, Warren Buffett (94) announced that he will transition the CEO role to his successor, Greg Abel, toward the end of the year.

The preceding figure, shown above, illustrates several companies positioned around the demarcation line of value creation. In the bottom right quadrant, you'll observe companies like Visa, Mastercard, and Microsoft, which achieve exceptional profit margins despite a relatively low turnover of their invested capital.

Conversely, in the top left quadrant, you'll find hardware and home improvement retailers such as Lowe's and Home Depot. These companies create value not through high margins, but by generating a high turnover of their invested capital.

A hybrid approach is also possible. Apple, for example, benefits from both a relatively high invested capital turnover and a comparatively high level of profitability.

Differentiation

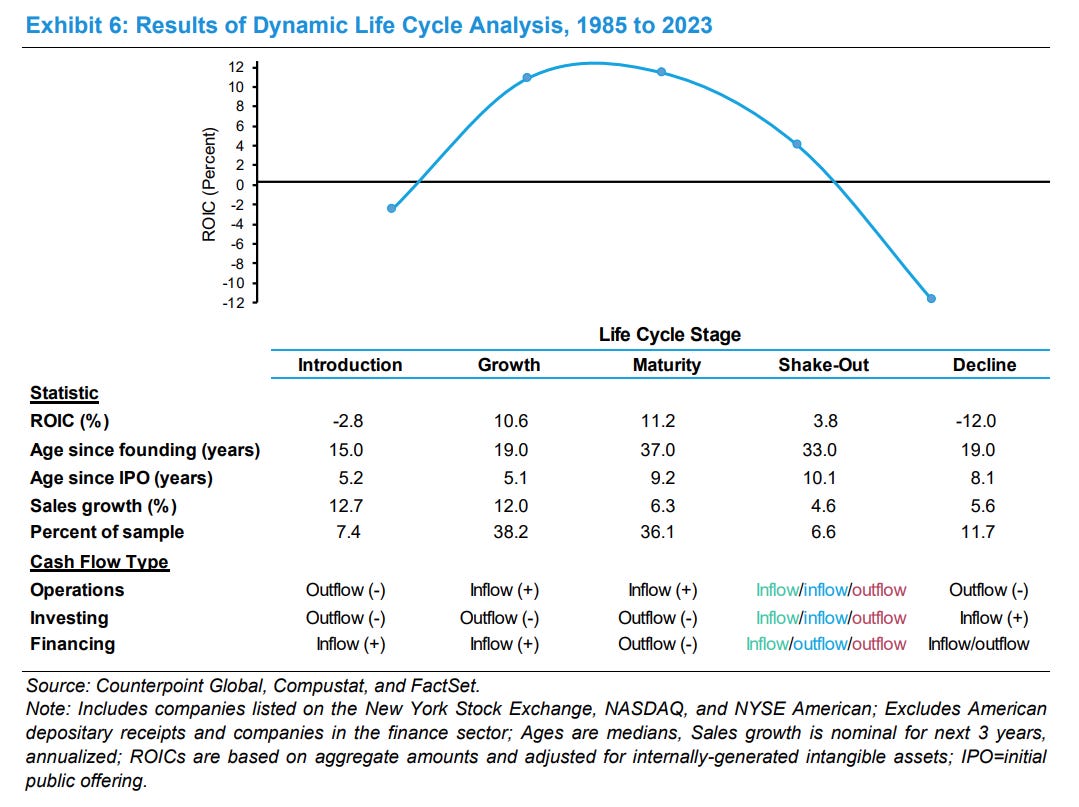

For sustained future value creation, beyond a high absolute ROIC, sufficient reinvestment opportunities are paramount. This is critical to prolong a company's "shake-out" and "decline" phases as much as possible.

Consequently, we seek companies adept at capitalizing on secular trends—the fundamental developments shaping our world. This enables them to reinvest their current cash flows, provided these reinvestments promise attractive (expected) returns, to generate future value. Companies that consistently demonstrate this capability are often referred to as compounders.

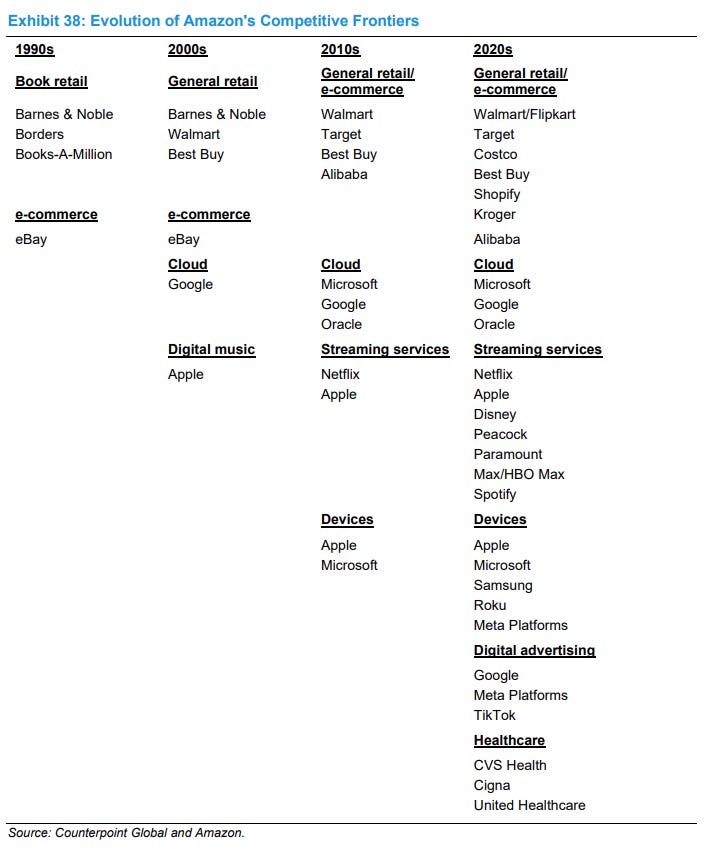

Case: Amazon

The Epitome of Differentiation

Amazon stands as a prime example of a company that has, since its inception in 1994, consistently tapped into new growth markets. This was achieved through a process of trial and error, with many projects ultimately yielding no significant returns.

Ultimately, what matters are the successful ventures. When these initiatives blossom into prosperous businesses, they contribute to an increase in a company's intrinsic value, which, over time, translates into the returns shareholders receive. This is because, over the long term, a company's stock price tends to align with the trajectory of its intrinsic value per share.

For us as investors, the sweet spot lies at the intersection of companies possessing strong moats that they effectively monetize through high capital turnover and/or robust profit margins (demonstrating high ROIC). Critically, these companies must also be strategically positioned to capitalize on secular trends, thereby creating new investment opportunities and paving the way for future compounding of returns.

Threats

However, it's crucial to exercise caution, as threats are perpetually lurking. It's not just direct competitors attempting to capitalize on high returns on investment. Suppliers, customers, and seemingly non-threatening companies from other sectors can also try to exert their influence to capture a share of a company’s value creation, or carve out a path most advantageous to themselves.

Therefore, in addition to assessing a company's strong competitive position, you'll want to comprehensively evaluate its moat, thoroughly analyzing the inherent tensions among all its stakeholders.

Ultimately, this endeavor aims to answer the core question: Is a company's moat strong enough to stand the test of time?

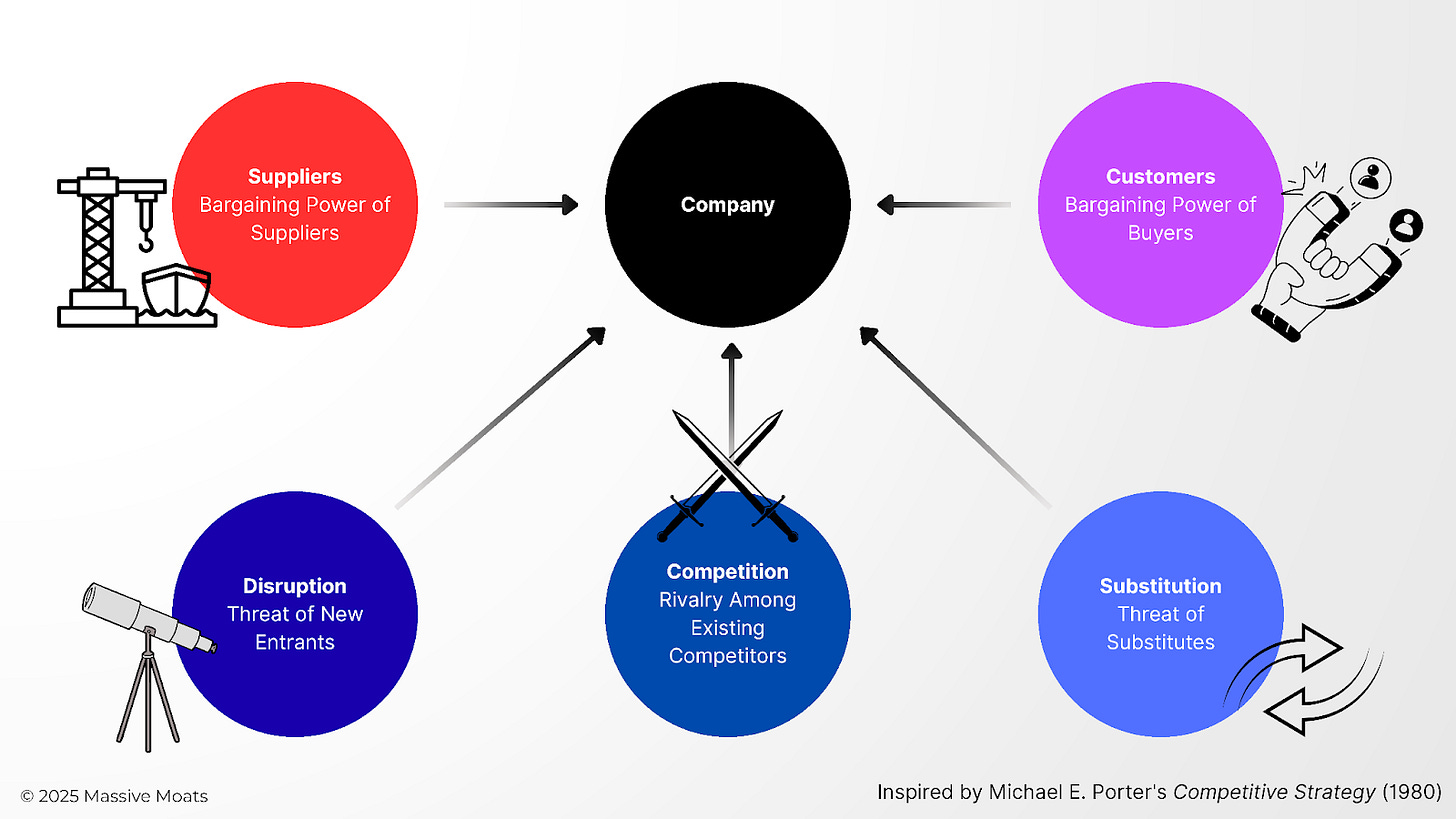

Porter’s Five Forces

Porter's Five Forces (1980) framework illustrates the five continuous forces that exert (or attempt to exert) influence on a company, its delta between revenue and the total cost to make this revenue, and consequently, the delta between its ROIC and WACC—the primary driver of value creation. These five forces are visually represented in the figure above, with a brief explanation provided below.

Suppliers

Suppliers can wield bargaining power over their customers when their negotiating position is strong. Consider a company like ASML, which holds a monopoly on EUV technology, effectively dictating prices to its customers such as TSMC, Samsung, and Intel.

Customers

Customers can exert power when they hold a strong negotiating position relative to their suppliers. Examples include large retail enterprises like Costco, Amazon, and Action, whose sheer scale grants them a superior bargaining position by their suppliers compared to smaller players.

Disruption

New entrants offering similar products or services more cheaply, efficiently, or with higher quality and service pose a significant risk to incumbent companies in a sector. A classic example is Uber's disruption of the traditional taxi industry.

Substitution

Substitution occurs when alternative solutions emerge that better address a "problem." Consider the transition from DVDs to streaming services, where Netflix charted a successful course, leaving its competitor Blockbuster adrift in a turbulent sea of technological innovation and shifts in consumer behavior.

Existing Rivalry

Forces are also exerted among existing competitors within an industry. Take the automotive industry, where companies like Ford, Volkswagen, and BMW compete with one another, often targeting similar customer segments through their strategies (Ferrari, within the automotive landscape, is an exception, catering to an entirely different demographic due to its pricing). Another example is supermarkets, which engage in activities like price wars to expand their market share, even if only marginally.

Sector Focus & Exclusions

Below are two figures displaying the ROIC ranges (20th - 80th percentile) and medians for various sectors. The sectors in which I currently hold investments are highlighted in blue.

Excluding Sectors?

The inherent characteristics of certain sectors lead me to proactively exclude them from my initial focus. These are typically sectors with a high commodity-like nature, where numerous companies compete by offering undifferentiated products and services, lacking a unique value proposition.

Consequently, I initially do not focus on companies in sectors such as telecommunications, utilities, (traditional) financial services (e.g., banks) and healthcare, oil and gas, metals and mining, biotechnology, the automotive industry, and airlines. While an individual company might, of course, be an exception and genuinely create value through distinct capabilities within such a sector—like Ferrari in the automotive industry, though I would arguably classify it within the luxury sector—my assessment is that other sectors, beyond those listed above, generally offer a more promising fishing pond for portfolio candidates.

Quality Investing = Moat Investing

A company's moat serves as a critical flywheel within the machinery of value creation. When meticulously maintained through all indirect decisions and capital allocations made by management, it positively impacts all processes and facets within a company:

A moat enhances a company's ability to benefit from higher margins and/or a higher asset turnover ratio.

This, in turn, contributes to higher absolute profitability and commensurate value creation.

A higher degree of value creation provides the financial capacity to perpetuate this value creation by seizing investment opportunities presented by the world's secular trends.

Ultimately, value creation enables a company to provide added value to all its stakeholders, including its employees, which can foster a positive corporate culture. Strong employers are subsequently better positioned to attract superior talent, leading to higher probabilities of future success, which in turn can lead to even greater value creation—a virtuous cycle.

Therefore, a moat is not merely a protective barrier around a company; it also forms the most important part of the engine for value creation. When actively maintained and guided by a management team that also pursues profitable growth opportunities, it becomes a powerful compounding machine.

In the upcoming articles, we will delve into the diverse landscape of moats and the categories into which they are commonly classified (e.g., intellectual property, switching costs, network effects, cost advantage, and efficient scale.)

Eelze Pieters

© 2025 Massive Moats

Disclaimer: NFA / E&OE. The information above is provided for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, accounting and/or financial advice. You should consult directly with a professional if financial, accounting, tax or other expertise is required.