A Deep Dive Analysis into Amazon.com, Inc.

What lessons can we derive from the origins of Amazon? How did it evolve from an online bookstore into one of the world's most valuable companies? And what does the future hold for Amazon?

Introduction

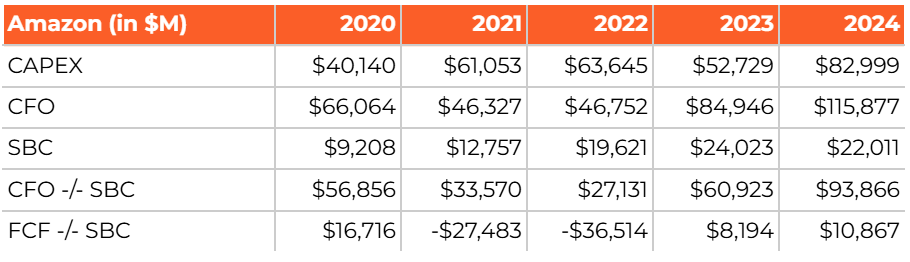

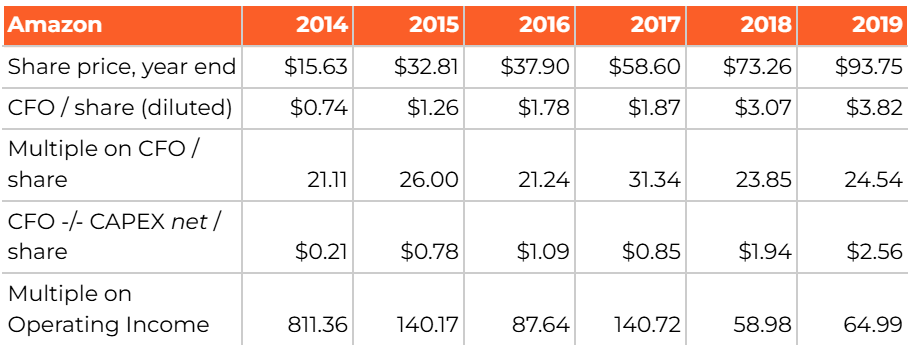

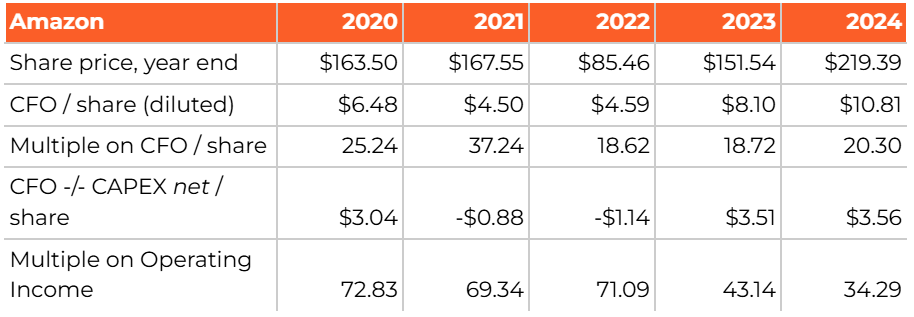

Amazon.com, founded by Jeff Bezos initially in a garage, would grow over three decades into one of the world’s largest companies. In its most recent fiscal year, 2024, the e-commerce giant recorded total sales of $638 billion, achieving an operating profit of $68 billion. With its robust operating cash flows amounting to $115 billion—adjusted to over $93 billion after accounting for stock-based compensation (SBC)—the company is well-positioned to make substantial investments. This particularly in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI), with Amazon allocating a total of $83 billion to capital expenditures (CAPEX) in 2024. For 2025, it is anticipated that the company will invest more than $100 billion, underscoring that it has long outgrown its origins as an online bookstore.

In this Deep Dive, I will guide you through the key milestones in Amazon’s inception and subsequent evolution, as well as the lessons we can glean from Jeff Bezos’ 27 years of entrepreneurial leadership. Among other topics, we will explore Bezos’ Regret Minimization Framework, Amazon’s Working Backwards Model, and its Flywheel concept, along with the influence of a co-founder and former CEO of another major U.S. retailer on these principles.

Next, Amazon will be examined as a conglomerate, comprising numerous business units stemming from internal projects and acquisitions integrated since its founding in 1994. This section will highlight current developments in the industries where Amazon operates and its positioning relative to competitors.

Following an analysis of Amazon’s financials, the foundations of its strong corporate culture will be outlined. This includes a discussion of Amazon’s 16 Leadership Principles and the role of Bar Raisers within the organization. The final chapters will address the risks and opportunities Amazon may face in the coming years.

Subsequently, through a valuation analysis, I will walk you through the market expectations for the sectors in which Amazon is active, as well as my specific perspective on the company. The discussion will conclude with a final summary.

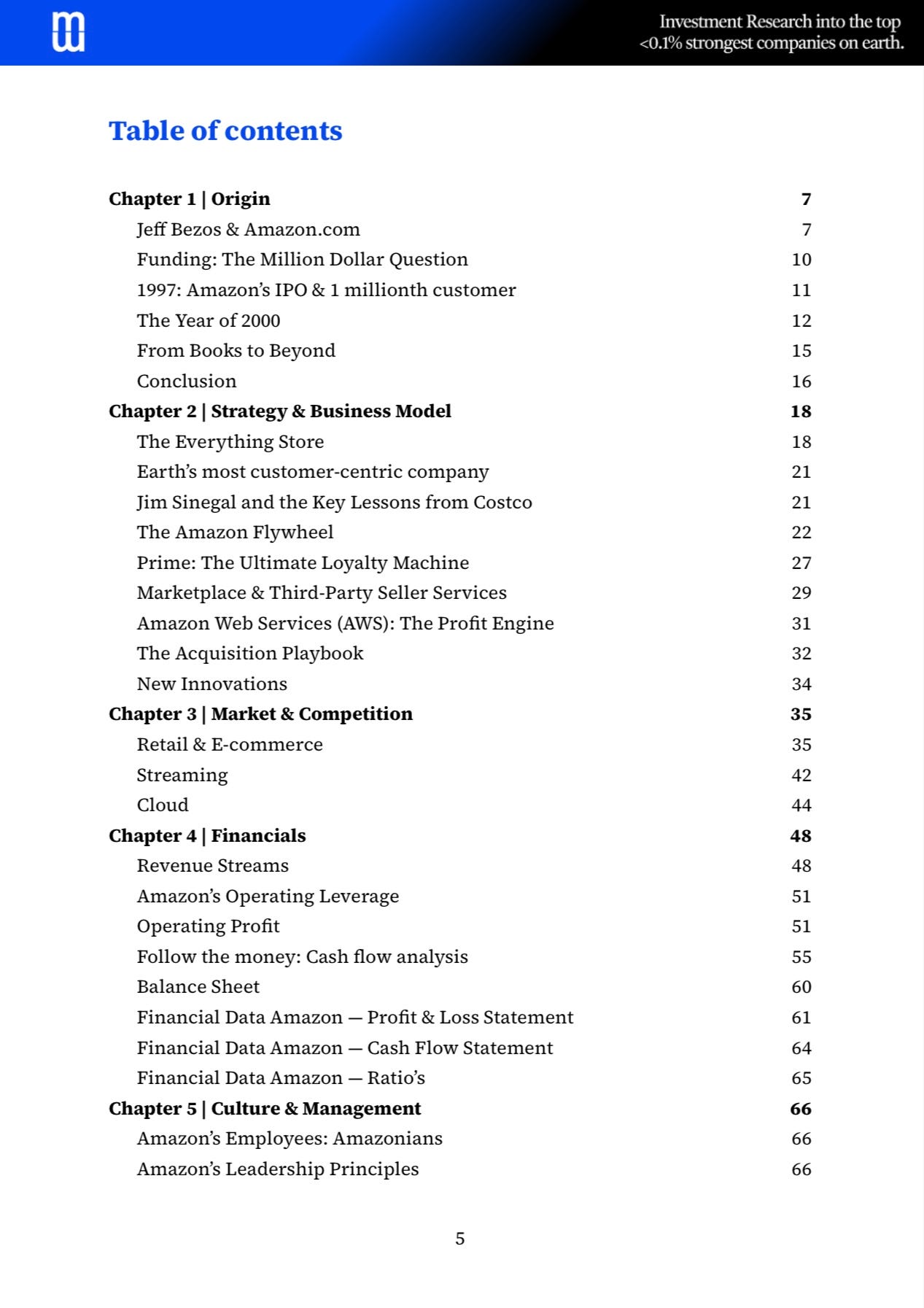

Below, you'll find the table of contents for this Deep Dive, derived from the PDF-version.

Chapter 1 | Origin

In 1994, Amazon was founded by Jeff Bezos, then 30 years old. Over the subsequent 27 years, Bezos transformed Amazon into one of the world’s largest companies, riding—and helping to shape—the digital revolution that would irrevocably alter our world. Below is a summary of Amazon’s history: a startup that, in 30 years, evolved into a conglomerate with a market value of $2 trillion.

Jeff Bezos & Amazon.com

Jeffrey Preston Bezos was born on January 12, 1964, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He grew up in Houston, Texas, and later in Miami, Florida, where, from a young age, he displayed a fascination with technology and science.

In 1986, he graduated summa cum laude from Princeton University with degrees in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Between 1986 and 1994, Bezos worked on Wall Street, eventually rising to the position of Senior Vice President at the hedge fund D.E. Shaw & Co. In this role, he was tasked with researching new, promising business opportunities, particularly in the technology sector and the nascent internet.

Amid the bustle of Wall Street, however, something far more significant captured Bezos’ attention—a figure that would change everything. The internet, still largely uncharted territory at the time, grew by a staggering 2,300% in 1993, according to Bezos in various interviews (e.g., 1997).

However, Brad Stone, author of The Everything Store, points to published works by John Quarterman, which note that the volume of bytes sent and data packets transmitted increased by factors of 2,057 and 2,560, respectively, between January 1993 and January 1994. Stone clarifies that the 2,300% figure cited by Bezos should therefore have been 2,300x—or 230,000%—rather than 2,300%. This leads Stone to highlight an interesting historical footnote: “Amazon began with a math error.”

The precise growth percentage of the internet in 1993 ultimately proves to be of little consequence; what mattered was that the internet ushered in an era of digital innovation.

When I'm 80, am I going to regret leaving Wall Street? No.

Will I regret missing the beginning of the Internet? Yes.

— Jeff Bezos

Jeff Bezos developed a simple yet profound principle: the Regret Minimization Framework. In this approach, he imagined himself as an elderly man looking back on his youth. Would he later regret clinging to his well-paid job and the security of Wall Street? Or would his regret stem instead from not pursuing new adventures—in Amazon’s case, the adventure of the internet—in an effort to turn his vision into reality?

The answer to that question soon became clear. In 1994, at the age of 30, Bezos decided to turn his back on Wall Street to capitalize on the internet’s explosive growth. Together with his wife, MacKenzie Scott, he packed up their belongings and embarked on a journey from New York to Seattle—the location Bezos envisioned as the ideal starting point for his new venture.

As the American landscape sped by during their drive to Seattle, Bezos refined his concept for an online book-selling website. He recognized an opportunity in the uniform, commodity-like nature of books, with millions of titles available worldwide. This allowed him to build a stronger position than traditional bookstores, which, in their physical locations, typically carried only a limited selection of titles. Bezos aimed to create a Universal Selection of books.

Once settled in Bellevue, Washington, where Bezos and his wife rented a home, the brainstorming quickly continued. The garage attached to the house was repurposed as a workspace. On July 5, 1994, Bezos incorporated the company as Cadabra Inc., a name inspired by “abracadabra.” However, he soon changed it that same summer after realizing “Cadabra” sounded too much like “cadaver.” Alternative names like Awake.com, Browse.com, and Relentless.com were all considered as potential foundations for his vision. If you enter these URLs into your browser today, they redirect to Bezos’ ultimate choice: Amazon.com, named after the mightiest river on Earth.

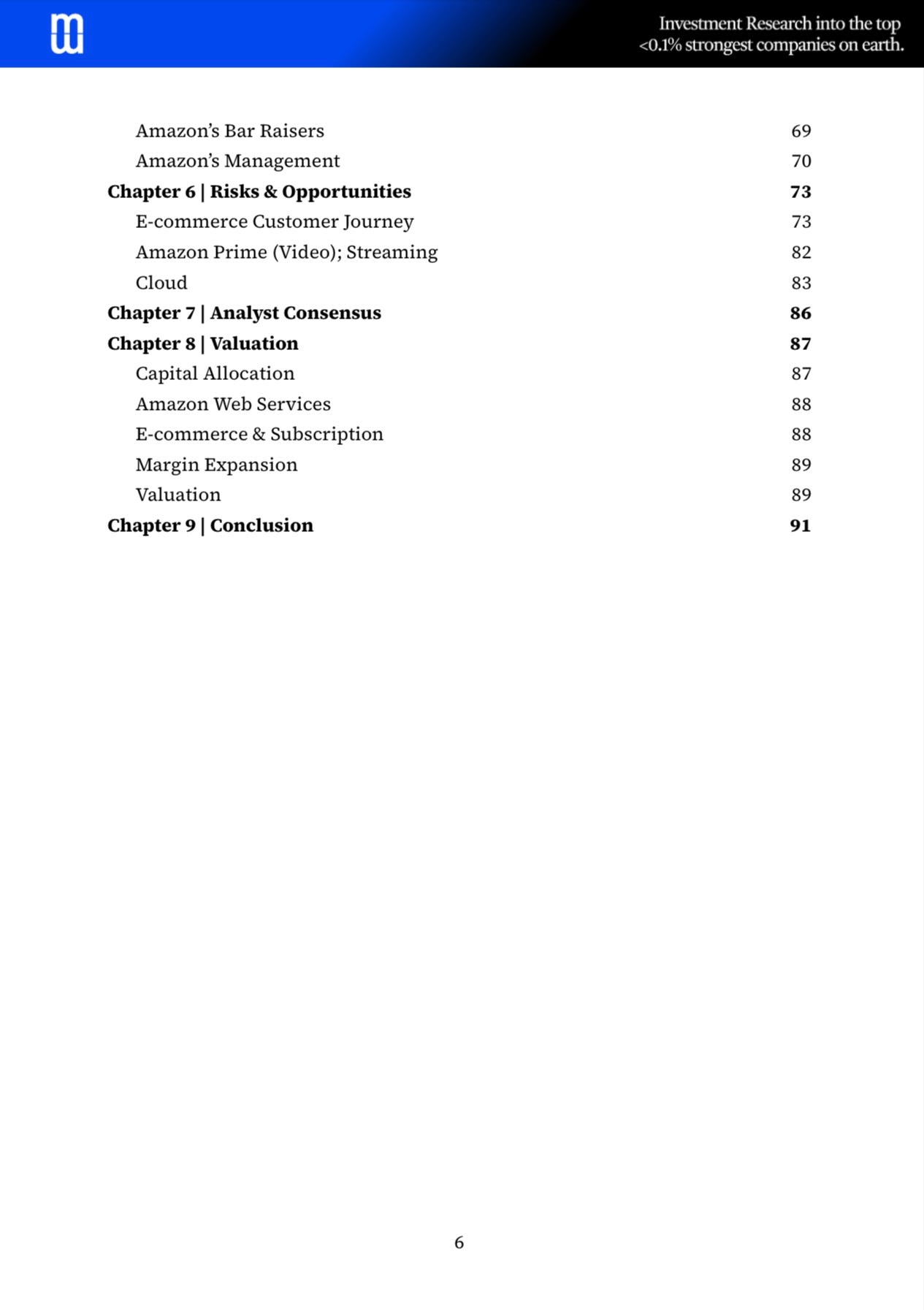

Below is a screenshot of Amazon.com’s gateway page from its early days.

Amazon established itself in Seattle for several reasons, including the startup-friendly business climate that Bezos viewed favorably (Microsoft was also based there) and the associated tax advantages. It was also convenient for Bezos that Ingram, one of the two largest book distributors at the time, was located not far away in Roseburg, Oregon.

Amazon.com officially launched on July 16, 1995, and quickly became a resounding success. Within the first month, Amazon had sold books to customers in all 50 U.S. states and 45 countries worldwide.

Bezos’ strategy centered on customer focus and innovation. He introduced customer reviews, personalized recommendations (such as the now-iconic “Customers who bought this also bought” feature), and an extensive range of titles, setting Amazon apart from traditional bookstores.

In 1998, Amazon expanded its offerings to include music and movies, followed by electronics, toys, and other products starting in 1999. This marked its transformation from an online bookstore into a fully-fledged e-commerce retailer.

Funding: The Million Dollar Question

The Amazon venture began with a $10,000 investment from Jeff Bezos himself. Additionally, Bezos secured $84,000 in interest-free loans from his inner circle. This formed the initial capital for the first 16 months.

Shel Kaphan, Amazon’s first employee and the architect of its coding and digital infrastructure, was contractually required by Bezos to invest $5,000 in the company. Bezos later emphasized multiple times that he valued fostering a sense of ownership among his employees, something he sought to achieve through equity.

In early 1995, Jeff Bezos’ parents, Jackie and Mike Bezos (Jackie being Jeff’s biological mother, while his biological father was Ted Jorgensen), invested $100,000, followed by an additional $145,000 later that year. In total, they entrusted Jeff with $245,000, which, according to Bezos, represented a significant portion of their savings.

They had faith in their son, despite Jeff’s candid warning that there was an estimated 70% chance they could lose their entire investment. It is reported that Bezos’ parents received a 6% stake in Amazon—an investment that, within a few years, would be worth millions and, decades later, balloon into billions.

However, this initial capital was insufficient to fuel Amazon’s growth, prompting Jeff to seek larger funding. By the end of 1995, Amazon raised $1 million. This reportedly required Bezos to hold 60 meetings with potential angel investors, 22 of whom ultimately wrote checks averaging $50,000 each (Startup Archive, 2024).

This $1 million was raised at a valuation of $5 million, meaning Bezos & co. had to relinquish 20% equity to these new investors—who, in hindsight, struck the deal of a lifetime at that moment.

The following year, in 1996, Silicon Valley-based venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (KPCB) acquired a 13% stake for $8 million, valuing Amazon at $60 million. John Doerr, a partner at KPCB, would later join Amazon’s board of directors at Bezos’ insistence.

1997: Amazon’s IPO & 1 millionth customer

On May 15, 1997, Amazon went public at $18 per share under the ticker $AMZN, raising $54 million at a valuation of $438 million—a significant increase from its $60 million valuation just one year prior.

The initial years as a publicly traded company were a golden era for Amazon shareholders. Between 1998 and 1999, the company underwent three stock splits (2:1, 2:1, and 3:1), meaning that shareholders who purchased a single share at the IPO would, in just over two years, hold 12 shares. By December 1999, these shares reached a peak of $113 each. In other words, one share bought in 1997 for $18 was worth [$113 x 12 =] $1,356 at its height by the end of 1999. This represented a stock price increase of over 7,400% in just 2.5 years.

In October 1997, Amazon.com reached the milestone of its millionth customer. To celebrate this achievement, CEO Jeff Bezos personally delivered the order. This required a trip to Japan, where he handed over the package—signed by every Amazon employee—to the customer (see photo above). That year, Amazon’s workforce grew from 158 to 614 employees, its distribution center space expanded from 50,000 to 285,000 square feet, and its inventory increased to over 200,000 titles.

Anticipating and capitalizing on the continued growth the internet would bring, Amazon invested heavily—a strategy that demanded significant capital. By the end of 1997, the company secured a $75 million credit facility (Amazon, 1997). In 1998, Amazon raised $530 million through the issuance of 10% “junk bonds” (CNN, 1998), followed by $1.25 billion in early 1999 via a convertible bond with a 4.75% interest rate. In February 2000, the company raised €690 million through the issuance of a convertible bond at 6.875% (The New York Times, 2000).

The Year of 2000

However, as with many technology companies, the years following the massive surge in their stock prices would prove challenging.

For Amazon specifically, a seemingly weakening balance sheet further contributed to its sharply declining stock price. “From a bond perspective, we find the credit extremely weak and deteriorating,” wrote Ravi Suria in 2000. Suria, then an analyst at Lehman Brothers specializing in convertible bonds, highlighted these concerns:

“We believe that the company will run out of cash within the next four quarters, unless it manages to pull another financing rabbit out of its rather magical hat.”

— Ravi Suria

Media outlets quickly latched onto this narrative. According to Bezos and his team, the claims were baseless—“pure unadulterated hogwash” (Amazon had raised €690 million earlier in 2000 and was sitting on nearly a billion dollars at the time). However, the story gained traction in the media, raising concerns within Amazon’s management that it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy—a phenomenon not unfamiliar in the media landscape. The fear was that suppliers might begin to doubt whether they would be repaid, potentially leading them to demand payment for previously delivered goods before fulfilling new orders. In essence, this could trigger a corporate equivalent of a bank run, particularly challenging for a company with a negative cash conversion cycle (see also the chapter on Strategy & Business Model).

The most anxiety-inducing thing about it was that the risk was a function of the perception and not the reality.

— Russ Grandinetti (treasurer at Amazon in 2000)

Amazon’s PR team devised a damage control plan, dispatching representatives to meet with major suppliers across the United States and Europe. Members of the finance department delivered presentations highlighting the company’s financial health. Bezos himself joined the effort, launching a charm offensive with the media.

Amazon’s stock price plummeted from its peak of $113 per share in December 1999 to $5.51 by October 2001. Shareholders who had bought in at the high faced a staggering -95% return. In other words, the stock would need to rise by approximately 2,000% from that point just to break even—a severe test of investor resilience.

In the FY2000 shareholder letter, Jeff Bezos reflected:

Ouch. It’s been a brutal year for many in the capital markets and certainly for Amazon.com shareholders. As of this writing, our shares are down more than 80% from when I wrote you last year. Nevertheless, by almost any measure, Amazon.com the company is in a stronger position now than at any time in its past.

Bezos went on to outline the progress the company had made over the previous year, including revenue growth (+68.3% compared to FY1999), gross profit growth (+125% year-over-year), and an increase in customers (+6 million year-over-year, reaching 20 million). He explicitly questioned why the stock price was significantly lower than in 1999, citing Benjamin Graham:

In the short term, the stock market is a voting machine; in the long term, it’s a weighing machine.

— Benjamin Graham

In his letter, Bezos also emphasized the following:

We’re a company that wants to be weighed, and over time, we will be—over the long term, all companies are. In the meantime, we have our heads down working to build a heavier and heavier company.

Bezos also reflected critically on his “bold bets”—investments in ventures such as Living.com and Pets.com, both of which ceased operations in 2000:

In retrospect, we significantly underestimated how much time would be available to enter these categories and underestimated how difficult it would be for single-category e-commerce companies to achieve the scale necessary to succeed. [...] As painful as that was, the alternative—investing more of our own capital in these companies to keep them afloat—would have been an even bigger mistake.

What’s done is done, however, and Bezos shifted his focus forward in the letter:

While we have a tremendous amount of work to do and there can be no guarantees, we have a plan to get there, it’s our top priority, and every person in this company is committed to helping with that goal.

Echoing his 1997 letter, he concluded: “It’s All About the Long Term.”

From that low of $5.51 in October 2001 (equivalent to $0.28 today), Amazon’s stock would soar by 70,250% to $192 by March 30, 2025, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 32%. Since its IPO in 1997, it has delivered a CAGR of 32.4%.

Thus, the long wait would ultimately pay off, despite the steep decline in stock price in 2000.

To close this section in Bezos’ own words: investing is indeed about the long term—though with the caveat that other scenarios for Amazon could have unfolded as well.

From Books to Beyond

As time progressed, Amazon’s product offerings expanded across multiple categories. Alongside the company’s growth came opportunities to streamline inefficient business processes. This included Amazon’s IT processes and department, where employees at one point spent 70% of their time working on the back-end systems, such as resolving IT and infrastructure issues (AWS, 2006).

Consequently, Amazon focused on building efficiencies within its own IT infrastructure, eventually extending these capabilities to third parties. This effort culminated in the summer of 2002 with the launch of the first version of “Amazon.com Web Services” (Amazon, 2002). In 2006, Amazon introduced S3 (“Simple Storage Service”) cloud storage and EC2 (“Elastic Compute Cloud”).

Jeff Bezos envisioned AWS as a utility that would deliver significant value to its users. During an S Team meeting prior to the EC2 launch, Bezos unilaterally adjusted a proposed rate—from $0.15 per computing hour—downward to $0.10.

This decision underscored Bezos’ distinctive philosophy of prioritizing lower (and even short-term negative) margins. At its core, this strategy was designed to attract customers, in contrast to a high-margin approach that might invite new competitors. It wasn’t until 2010 that Microsoft launched Azure globally (Microsoft, 2010), followed by Google with its Compute Engine in 2012 (Google, 2012).

The combination of storage (S3) and computing power (EC2) proved to be a winning formula, enabling AWS to become a cornerstone of Amazon’s contributions to technological innovation in today’s world.

Simultaneously, Amazon introduced the Kindle in 2007, once again revolutionizing the book market by pioneering the e-book sector (Amazon, 2007). The Kindle’s origins trace back to 2004, when Lab 126, one of Amazon’s subsidiaries, was tasked by Bezos with “building the world’s best e-reader before Amazon’s competitors could.”

In 2017, Amazon acquired the supermarket chain Whole Foods Market for $13.7 billion. In the press release announcing the acquisition, Amazon stated that, starting the following Monday, it would lower the prices of a selection of best-selling products, “with more to come” (Amazon, 2017).

Throughout the 2010s and 2020s, Amazon experienced significant growth. It expanded its Amazon Prime (and Video) offerings and pursued internal projects such as Alexa. The company also invested heavily in logistics and introduced Prime memberships with expedited delivery options.

In July 2021, Andy Jassy, the former head of AWS, succeeded Jeff Bezos as CEO. Bezos stepped down from the CEO role but retained his position as Executive Chair. More details about both individuals can be found in the chapter on Culture & Management.

Conclusion

From a book-trading startup in a small garage to a technology giant with global impact, Amazon has undergone extraordinary growth over the past 30 years. The vision and determination of Jeff Bezos played a pivotal role in the company’s success. Despite numerous challenges, Bezos and his team transformed Amazon into a leading player in the digital economy.

As I have aimed to illustrate in this chapter, Amazon’s origins are a fascinating story, offering a wealth of lessons to draw upon. These insights will be further explored in the upcoming chapters of this Deep Dive.

The preceding chapter provides a summary of Amazon’s history, compiled from the extensive information available about the company. Below is a list of additional sources consulted that have not already been cited.

Wikipedia pages on Jeff Bezos (2025), Amazon (2025) and AWS (2025).

The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon by Brad Stone (2013)

Amazon Unbound: Jeff Bezos and the Invention of a Global Empire by Brad Stone (2021)

Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets from Inside Amazon by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr (2021)

Acquired’s Amazon.com Episode (Youtube, 2022)

Acquired’s Amazon Web Services Episode (Youtube, 2022)

Chapter 2 | Strategy & Business Model

The Everything Store

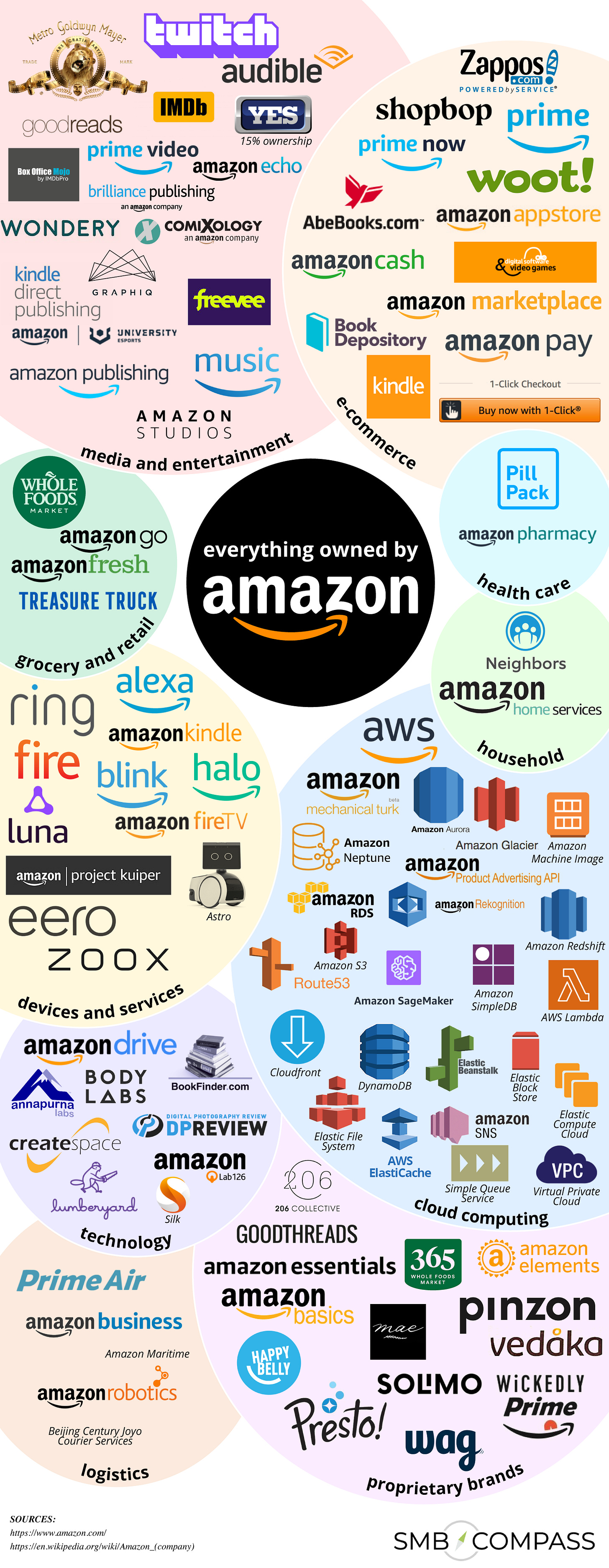

Amazon has evolved into a conglomerate of various companies and business units, all of which collectively contribute to the strength of the enterprise. Below is an overview of Amazon’s operations:

The company engages in e-commerce activities through Amazon.com and 21 regional extensions, as well as its apps, where it sells products from its own inventory.

Additionally, third-party sellers offer their goods via Amazon’s platforms, with Amazon facilitating the connection between supply and demand while also providing services in logistics, shipping, financing, and marketing.

Through Amazon Web Services (AWS), the company delivers cloud-based services, including data storage and computing power.

Amazon also encompasses entities such as Whole Foods, Zappos, Twitch, IMDb, Ring, Audible, Kindle, and Goodreads. Furthermore, businesses like Souq.com (now Amazon.ae)—the largest e-commerce website in the United Arab Emirates—MGM Holdings (now Amazon MGM Studios), and One Medical (now Amazon One Medical) have been fully integrated into Amazon.

With Amazon Prime, the company offers a subscription service that provides members with numerous benefits, including advantages within its e-commerce division and access to streaming content on Amazon Prime Video.

Amazon also leverages the distribution power of its platforms to generate revenue from advertising.

As a result, Amazon’s influence extends deeply into various sectors, including retail & e-commerce, health & wellness, technology & cloud services, and media & entertainment.

Amazon operates a global network of over 200 fulfillment centers (Amazon, 2025). Additionally, through Amazon Air, it maintains a fleet of 98 aircraft (Wikipedia, 2025), complemented by 120,000 trucks and delivery vans (Amazon, 2025).

Earth’s most customer-centric company

At the core of Amazon’s strategy, the customer reigns supreme: “We strive to be Earth’s most customer-centric company” (Amazon, 2025). Amazon’s employees are guided by four key principles:

An obsession with the customer.

A passion for invention.

A commitment to operational excellence.

All underpinned by a long-term mindset.

Amazon is guided by four principles: customer obsession rather than competitor focus, passion for invention, commitment to operational excellence, and long-term thinking. We strive to be Earth’s most customer-centric company, Earth’s best employer, and Earth’s safest place to work.

— Amazon (2025)

Jim Sinegal and the Key Lessons from Costco

As outlined in the previous chapter, the period around the turn of the millennium was a defining moment for Amazon. Not only was the company’s survival put to the test, but Jeff Bezos was also prompted to reflect on the path he wanted Amazon to take in the years ahead.

On a Saturday afternoon in the spring of 2001, Bezos gained new insights that would have a lasting impact on Amazon’s success over the ensuing decades.

At a Starbucks table inside Bellevue’s Barnes & Noble, Bezos met with Jim Sinegal, the co-founder and then-CEO of Costco Wholesale. Bezos’ initial intent was to ask whether Amazon could purchase products from Costco that it couldn’t yet source directly from certain suppliers. Sinegal declined this proposal but shared valuable lessons from his decades of retail experience at Costco and, prior to that, FedMart. Central to his philosophy was the importance of customer loyalty (Stone, 2013).

The following Monday, Bezos gathered Amazon’s management team and announced a shift in the company’s pricing strategy: Amazon should adopt “everyday low prices,” mirroring Costco’s approach. In the months that followed, Amazon reduced the prices of books, music, and videos by 20-30% (Amazon, 2001-2002; Stone, 2013).

The above sentences are derived from Brad Stone’s account of these pivotal spring days in 2001, as detailed in his book The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon (2013).

There are two kinds of retailers: there are those folks who work to figure how to charge more, and there are companies that work to figure how to charge less, and we are going to be the second, full-stop.

— Jeff Bezos (analyst call, Q2 2001)

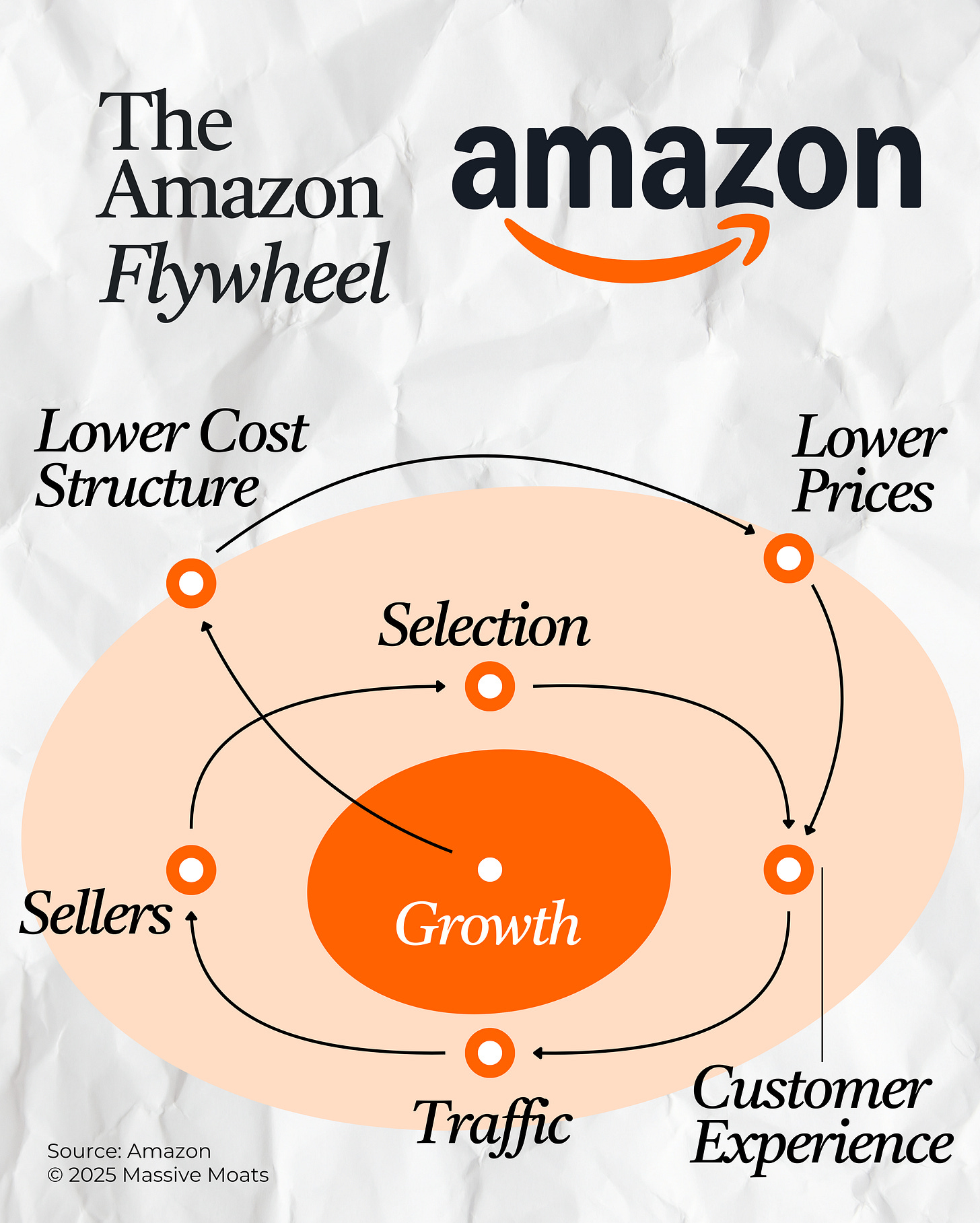

The Amazon Flywheel

In the fall of 2001, Amazon provided further context for its updated business model by developing what would become its Flywheel model. This flywheel reflects Amazon’s focus on achieving high customer satisfaction—a cornerstone that has underpinned its growth into a company with a market capitalization of $2 trillion.

The origins of Amazon’s Flywheel trace back to 2001, when Jeff Bezos sketched it on a napkin during a brainstorming session with Jim Collins, a renowned business consultant and author of Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...And Others Don’t (2001). Collins introduced the flywheel concept as a metaphor for exponential growth. Bezos and his team refined this idea into what is now known as The Amazon Flywheel, as depicted in the image below.

Amazon’s Flywheel consists of several interconnected components that reinforce one another and drive the momentum of the overall system:

The primary focus is on achieving high customer satisfaction, serving as the central axis around which the flywheel operates.

A superior customer experience, in turn, ideally attracts more customers.

A larger customer base enhances the platform’s appeal to third-party sellers and advertisers.

More sellers contribute to a broader and improved product offering.

A better product offering increases customer satisfaction and drives more purchases on Amazon’s platforms.

Higher sales volume fuels growth.

Growth enables Amazon to achieve economies of scale and reduce per-unit costs.

Lower costs allow Amazon to further decrease prices, perpetuating the flywheel’s cycles and accelerating its momentum.

The session with Jim Collins proved pivotal for Amazon and the refinement of its updated strategy.

Amazon executives were elated; according to several members of the S Team at the time, they felt that, after five years, they finally understood their own business. But when Warren Jenson asked Bezos if he should put the flywheel in his presentations to analysts, Bezos asked him not to. For now, he considered it the secret sauce.

— Brad stone (The Everything Store, 2013)

Nevertheless, Jeff Bezos shared a concise summary of Amazon’s Flywheel in his FY2001 Shareholder Letter:

Focus on cost improvement makes it possible for us to afford to lower prices, which drives growth. Growth spreads fixed costs across more sales, reducing cost per unit, which makes possible more price reductions. Customers like this, and it’s good for shareholders.

— Jeff Bezos (Shareholder Letter 2001)

The impact of the conversation with Jim Sinegal on that single Saturday afternoon in the spring of 2001 added a critical pillar to Amazon’s strategy:

Until July, Amazon.com had been primarily built on two pillars of customer experience: selection and convenience. In July, as I already discussed, we added a third customer experience pillar: relentlessly lowering prices. You should know that our commitment to the first two pillars remains as strong as ever.

— Jeff Bezos (Shareholder Letter 2001)

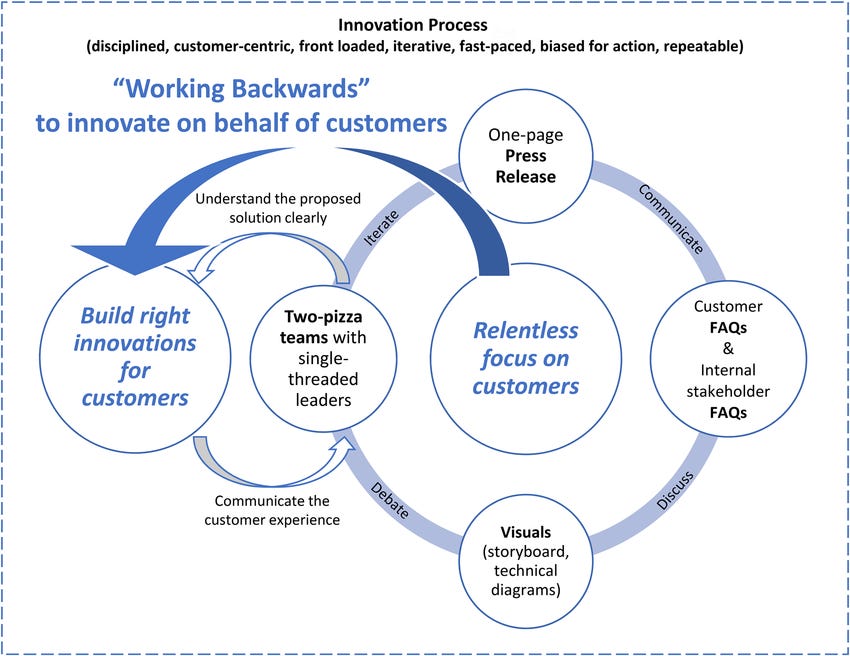

Working Backwards

Amazon’s customer-first approach is further illuminated by the methodology it employs in its business processes, particularly in brainstorming and developing new consumer products and services.

“Working Backwards” refers to a process in which new ideas at Amazon are approached by first envisioning the final product or service, complete with a draft press release for its launch. Today, the term has been broadened and is used more generally to describe processes that are reversed, reasoning backward from the end state. As Charlie Munger would say, “Invert, always invert.”

In the book Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets from Inside Amazon (2021), authors Colin Bryar and Bill Carr—former Amazon employees with 12 and 15 years of experience, respectively—explain the theory behind Working Backwards through practical examples.

Both Bryar and Carr were involved with Kindle, Amazon’s e-reader, where the Working Backwards principle was first applied:

We were working forward, trying to invent a product that would be good for Amazon, the company, not the customer. When we wrote a Kindle press release and started working backwards, everything changed. We focused instead on what would be great for customers. An excellent screen for a great reading experience. An ordering process that would make buying and downloading books easy (…)” (2021).

Later, FAQs were incorporated into this model, requiring teams to draft answers to anticipated questions from stakeholders and customers in advance. This fosters a clear vision before development begins, enabling Amazon to create more customer-centric products.

Bryar and Carr now work as consultants through their company, Working Backwards LLC, where they coach executives from both large (publicly listed) corporations and startups on implementing management practices developed at Amazon (Working Backwards, 2025).

For more on the origins and underlying theory of the Working Backwards Model, refer to the book Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets from Inside Amazon by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr (2021).

Inventory Management & Negative cash conversion cycle

Amazon’s (online) stores leverage mechanisms similar to those mastered by Costco Wholesale, enabling the company to benefit from a negative cash conversion cycle. Amazon explains this in its reporting, noting its aim to convert inventory into cash more quickly than it is required to pay its suppliers for the purchased goods.

We seek to turn inventory quickly and collect from consumers before our payments to vendors and sellers become due.

— Amazon (2025, p. 20)

Unlike a retailer such as Costco Wholesale, Amazon does not separately disclose its Merchandise Costs in its financial statements; only the Cost of Sales is reported. This figure encompasses not only the cost of purchased products but also expenses related to order shipping, as well as costs associated with sortation and delivery centers.

As a result, it is not possible to precisely calculate Amazon’s negative working capital related to inventory or its inventory turnover rate. However, a rough estimate can be provided.

For FY2024, Amazon recorded an average inventory level of approximately $33.8 billion, calculated by averaging the beginning and ending inventory levels across the quarters of FY2024. With this average inventory, Amazon facilitated “net product sales” of $272.3 billion, which includes a certain gross margin for Amazon itself. Depending on the size of this gross margin, Amazon’s inventory turnover could reach a maximum of 8x, assuming the reported inventory pertains solely to these Net Product Sales and that inventory levels do not fluctuate significantly between quarterly balance sheet dates.

This implies that Amazon sells its inventory in >45 days, positioning the company well to capitalize on the benefits of paying its suppliers 30-120 days after delivery.

By comparison, Costco’s inventory turnover for FY2024 was 12.6x, meaning it sold its purchased merchandise within an average of 29 days in 2024. With an average Merchandise Inventories level of $17.7 billion, Costco generated revenue of $249.6 billion in FY2024 (Massive Moats, 2025).

Amazon’s inventory figures exclude the stock it manages for its third-party sellers, as the economic ownership of this inventory remains with those third parties. Consequently, the revenue generated by these third-party sellers is not included in Amazon’s (product) sales; instead, Amazon recognizes revenue from the commissions it earns on these third-party services.

Prime: The Ultimate Loyalty Machine

The precursor to what is now Amazon Prime originated in 2005, when Amazon introduced its first membership program, priced at $79 per year for U.S. consumers (Amazon, 2005). In return, customers received unlimited, free express two-day shipping with no minimum order threshold. Jeff Bezos described Amazon Prime as “all-you-can-eat express shipping” in the press release, once again emphasizing the goal of fostering long-term customer relationships:

Though expensive for the Company in the short-term, it's a significant benefit and more convenient for customers. With Amazon Prime, there's no minimum purchase to think about, and no consolidating orders -- two-day shipping becomes an everyday experience rather than an occasional indulgence.

— Jeff Bezos (2005)

Since then, numerous benefits have been added for Amazon Prime members. In September 2006, Amazon launched Amazon Unbox, later rebranded as Amazon Instant Video, coinciding with the acquisition of the remaining stake in LoveFilm in early 2011. This laid the foundation for Amazon Prime members to access video content. In 2015, the “Instant” label was dropped, resulting in the creation of Amazon Video.

In 2021, Amazon acquired the film studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) for $8.45 billion (Amazon, 2021). This acquisition added thousands of titles to Amazon’s IP-library, including acclaimed series such as The Handmaid’s Tale (8.3/10, IMDB), Fargo (8.8/10, IMDB) and Vikings (8.5/10, IMDB). Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was subsequently renamed “Amazon MGM Studios.”

On Amazon Prime Video, members have access to tens of thousands of video content titles. Beyond Prime Video, Prime members enjoy benefits such as Prime Music, Prime Reading, Prime Photos, Prime Gaming (including a Twitch subscription), and additional perks like exclusive deals during events such as Prime Day, as well as discounts at Amazon Fresh and Whole Foods. This is, of course, in addition to free shipping and shipping benefits on Amazon’s e-commerce platform.

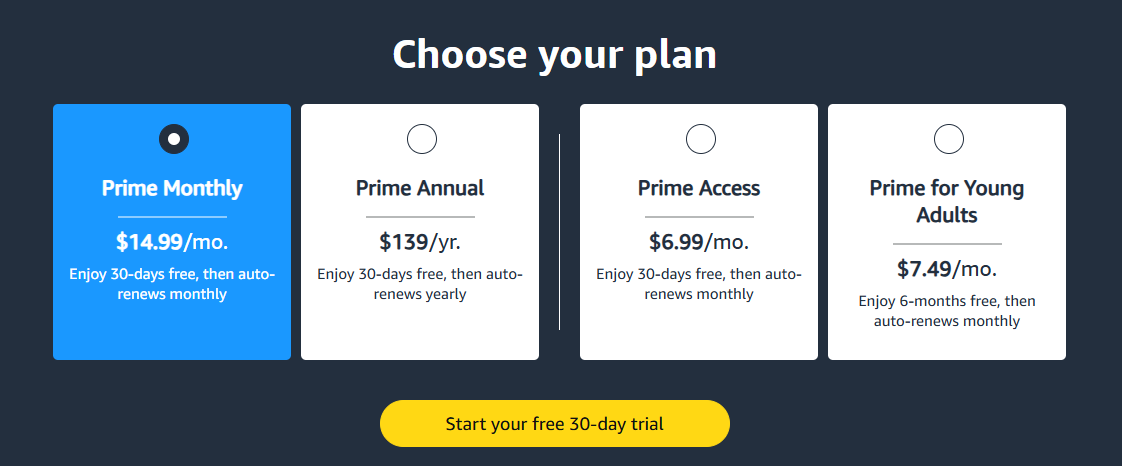

The cost of Amazon Prime varies by location. In the Netherlands, it is priced at €4.99 per month (€49.90 per year), while in the United States, it costs $14.99 per month ($139 per year) to join Amazon Prime.

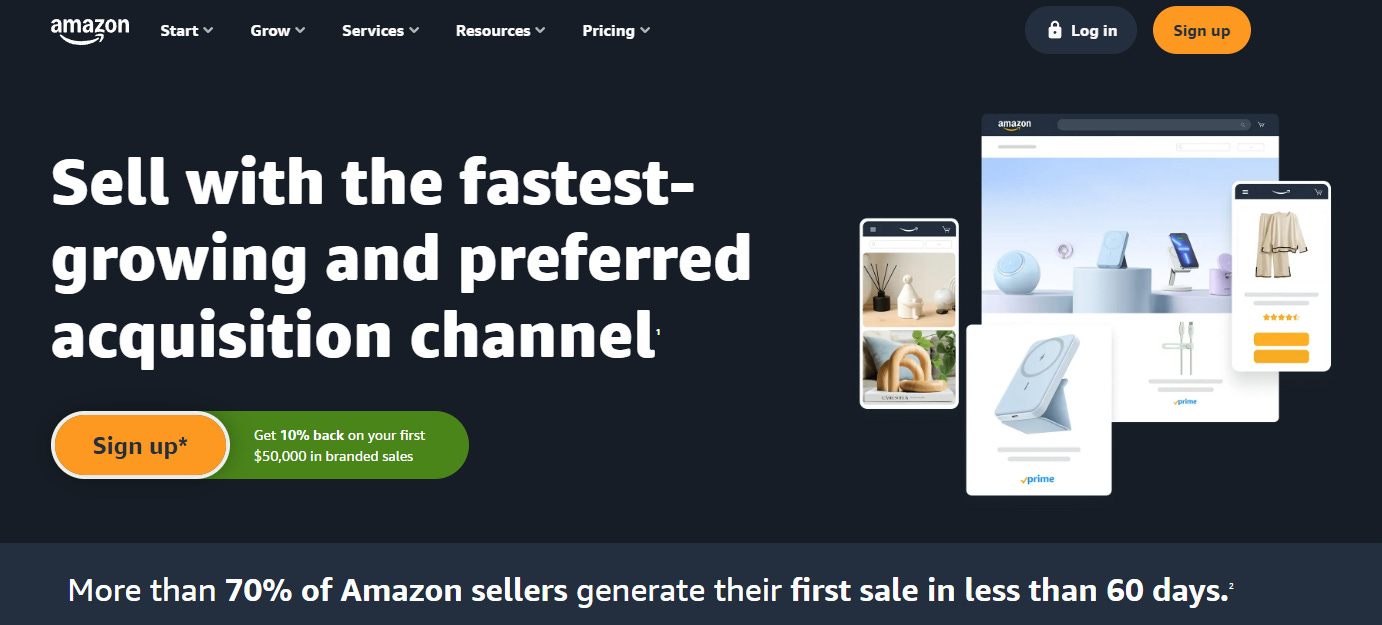

Marketplace & Third-Party Seller Services

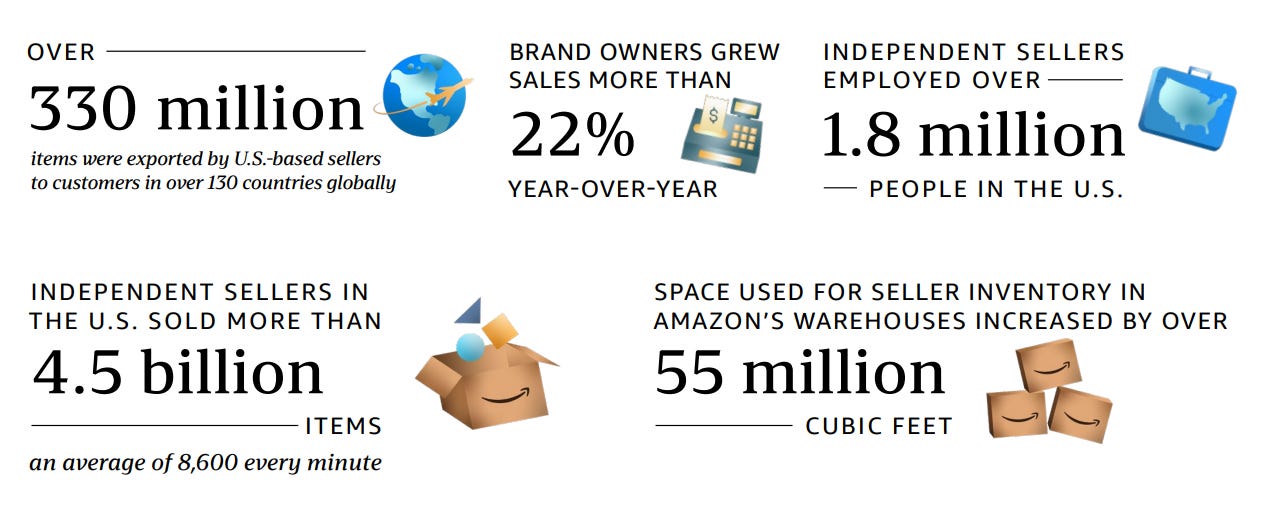

In 2023, third-party sellers in the United States sold 4.5 billion items—averaging 8,600 items per minute—according to Amazon (2024). In dollar terms, this represented a 22% increase compared to 2022. Of these, over 330 million items were shipped internationally, destined for locations outside the United States.

In 2023, Amazon added more than 100,000 new third-party sellers to its platform. Over 60% of the Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) was attributed to third-party sellers, the majority of whom are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), as reported by Amazon (2024).

Amazon generates revenue from third-party sellers through multiple channels. It charges a fixed fee of €39/$39.99 per month (or €/$0.99 per item for very small sellers, i.e., those selling fewer than 40 products per month). Additionally, sellers pay a commission, known as a Referral Fee, which varies by product category and typically ranges between 5% and 20%.

Sellers utilizing Amazon’s Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) service incur additional fees, which include fulfillment costs and shipping expenses. These consist of inventory storage fees, calculated based on a seller’s daily average inventory volume (expressed in cubic feet or meters), and fulfillment fees, which are billed per packed order (per unit) and cover packaging and shipping costs. The latter shipping costs depend on the size and weight of the sold products.

Amazon claims that its fulfillment costs are 70% lower than comparable premium options offered by other fulfillment providers in the United States (Amazon, 2024).

Furthermore, sellers using Amazon’s services pay a monthly fee for items stored in fulfillment centers for more than 271 days (Amazon, 2025), as well as potential removal fees.

Personally, in 2024, I was approached by an Amazon account manager regarding selling on their platform for my e-commerce webshop. I received a well-crafted email containing information and an invitation to a no-obligation introductory meeting. The email also outlined the benefits new sellers could gain by joining Amazon’s network, including strategic advice on registration and EU compliance, international selling, and marketing and fulfillment solutions. This demonstrates Amazon’s proactive efforts to recruit new third-party sellers.

Amazon Web Services (AWS): The Profit Engine

Amazon Web Services (AWS) provides on-demand cloud computing services to businesses and governments worldwide, operating on a pay-as-you-go model where customers are billed based on actual usage. Additionally, AWS offers autoscaling capabilities, allowing customers to scale computing resources up or down as needed, depending on fluctuations in demand.

These accessible, on-demand web services filled a market gap when they were introduced by Amazon at the start of this century. Traditionally, companies had to establish their own hardware infrastructure—such as servers—purchasing equipment from vendors like Cisco or IBM or leasing space for it. This approach required additional payments for updates, maintenance, or capacity upgrades to accommodate peak usage periods.

In contrast, AWS offered customers significantly greater flexibility, lowering the barriers to making certain investments. This flexibility played a crucial role in driving the digitalization and global expansion of businesses. By effectively relieving customers of hardware-related concerns, AWS enables companies to shift their focus toward front-end operations.

When establishing AWS, Amazon prioritized delivering top-tier web services, including automatic updates for customers, ensuring the highest possible service quality.

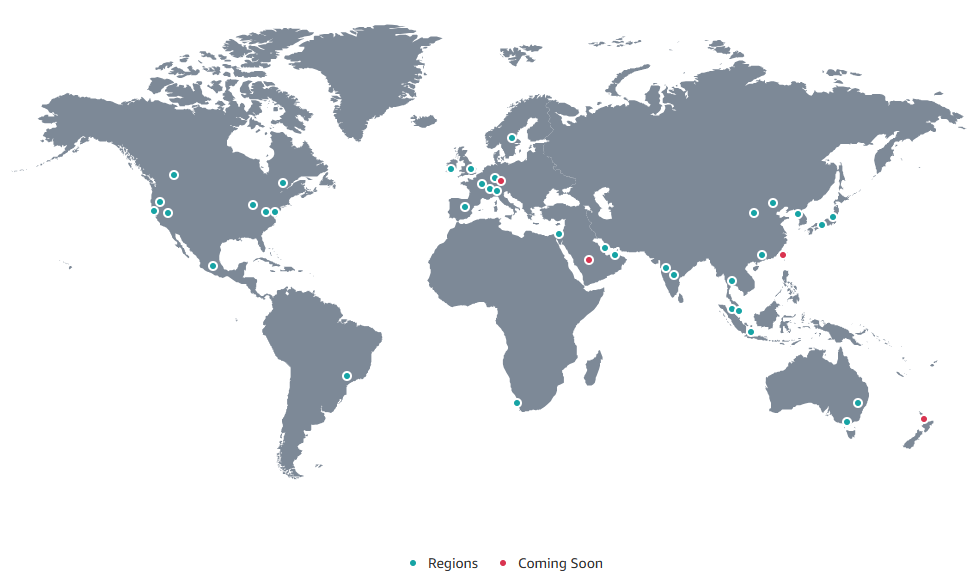

As of March 2025, AWS operates 114 Availability Zones. These are distinct locations within an AWS region, designed for fault isolation and high availability. Each Availability Zone is physically separate, equipped with independent power, cooling, and networking infrastructure.

Currently, AWS maintains a physical presence in 36 geographic regions, with four additional regions in development: New Zealand, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, and an extra server in Germany (AWS European Sovereign Cloud), as illustrated in the image below.

The revenue generated from Amazon Web Services (AWS) enabled the company to sustain lower margins on its e-commerce operations. This financial flexibility was a key factor in allowing Amazon to establish a dominant position within the e-commerce sector.

The Acquisition Playbook

Amazon gleaned valuable lessons from its bold bets during the internet boom at the end of the last century. Investments in ventures like Living.com and Pets.com, which significantly weighed on Amazon’s overall intrinsic value, ultimately proved to be capital-destructive. Reflecting on these experiences, Amazon adjusted its approach, as evidenced by the scale of its major acquisitions over the past 25 years. The acquisitions it pursued were all relatively smaller in size when measured against Amazon’s total valuation.

The largest acquisitions in Amazon’s history include:

Whole Foods Market in 2017 ($13.7 billion);

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 2021 ($8.45 billion);

One Medical in 2022 ($3.9 billion);

Zappos in 2009 ($1.2 billion);

Zoox in 2020 ($1.2 billion);

Twitch in 2014 ($970 million); and

Ring in 2018 ($839 million).

Nearly all of the projects currently driving Amazon’s success originated internally. These began as ideas from Amazon employees that evolved into projects, eventually maturing into new products, services, or even standalone businesses like AWS. Additionally, Amazon has made numerous smaller acquisitions that were subsequently integrated into larger, pre-existing segments of the company as add-ons.

New Innovations

Innovation is deeply embedded in Amazon’s culture. The company is currently engaged in several projects aimed at future advancements. For instance, in December 2024, Amazon issued a press release announcing its intent to develop Amazon Nova, an AI Foundation Model designed to facilitate the creation and scaling of AI applications (Amazon, 2024).

Additionally, under Project Kuiper in 2024, Amazon constructed a 172,000-square-foot satellite production facility in Kirkland, Washington, while also investing $19.5 million to expand its satellite operations at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (Amazon, 2024). Through Project Kuiper, Amazon aims to establish a network of over 3,000 low Earth orbit satellites.

Inside Amazon, we have about 1,000 generative AI applications in motion, and we’ve had a bird’s-eye view of what application builders are still grappling with. Our new Amazon Nova models are intended to help with these challenges for internal and external builders, and provide compelling intelligence and content generation while also delivering meaningful progress on latency, cost-effectiveness, customization, Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), and agentic capabilities.

— Rohit Prasad, SVP of Amazon Artificial General Intelligence

Chapter 3 | Market & Competition

Given the vast scope of Amazon’s operations, which span multiple industries, the company faces numerous peers and (semi-)competitors. Amazon succinctly captures this competitive landscape in the following statement:

We Face Intense Competition

Our businesses are rapidly evolving and intensely competitive, and we have many competitors across geographies, including cross-border competition, and in different industries, including physical, e-commerce, and omnichannel retail, e-commerce services, web and infrastructure computing services, electronic devices, digital content, advertising, grocery, healthcare, communications, and transportation and logistics services.

— Amazon (AR2024)

As it would be impractical to individually address the hundreds of direct and indirect competitors Amazon encounters, I have outlined below the developments within three key sectors:

Developments in the Retail & E-commerce sector (in relation to Amazon E-commerce Platforms & Advertising);

Developments in the Streaming sector (in relation to Amazon Prime Video & Subscriptions);

Developments in the Cloud sector (in relation to Amazon Web Services).

Retail & E-commerce

With Amazon, Jeff Bezos capitalized on the emerging developments of the internet. In its early days, Amazon entered the retail space as an e-commerce company focused on books, later expanding to include other product categories.

The internet, partly propelled by Amazon’s influence, shifted a portion of physical retail sales to the e-commerce sector. According to The Census Bureau of the Department of Commerce (2025), e-commerce accounted for 16.1% of total retail sales in the United States in 2024. The graph below illustrates the evolution of e-commerce’s share of total retail sales in the U.S. since Q4 1999.

From Q4 1999 to Q4 2024, the e-commerce market in the United States grew from 0.6% to 16.4% of total retail sales. The graph above also highlights a sharp increase in 2020, driven by the pandemic, followed by a subsequent normalization. For Europe, this percentage is estimated to be around 16% in 2024 (Forrester, 2025). According to Statista (2025), e-commerce sales in China reached 26.8% of total retail sales in 2024, a figure significantly higher than in the Western world.

By 2029, this share is projected to rise further to approximately 21% globally (Statista, 2025). In other words, e-commerce sales are expected to grow at a faster pace in the coming years than the offline retail sector. This aligns with the trend observed since 1999, as indicated by an R² value of 0.922 in the graph above.

This trend suggests that e-commerce players like Amazon will benefit from continued tailwinds in the years ahead, driven by both increased internet usage worldwide (step 1) and a rise in online purchases (step 2).

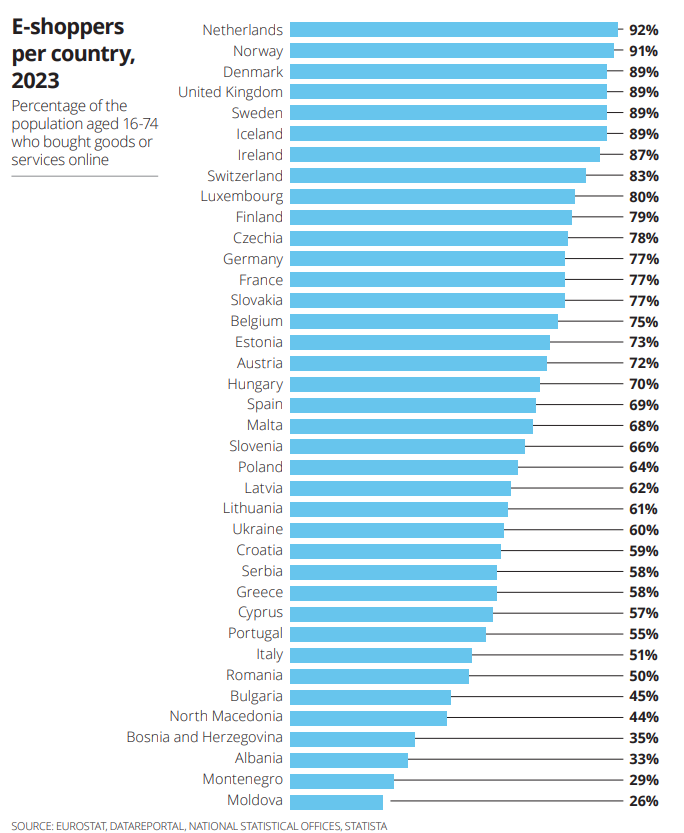

In the Western world, internet adoption is already well integrated. The table below presents the percentage of residents aged 16–74 in European countries who have purchased products or services online. The Netherlands leads with 92%, followed by Norway (91%) and Denmark (89%).

In 2023, an estimated 92% of Dutch residents were the most accustomed to purchasing products and services online. Other countries, particularly in Eastern Europe, as well as countries like Italy (51%), are expected to see their percentages rise in the coming years.

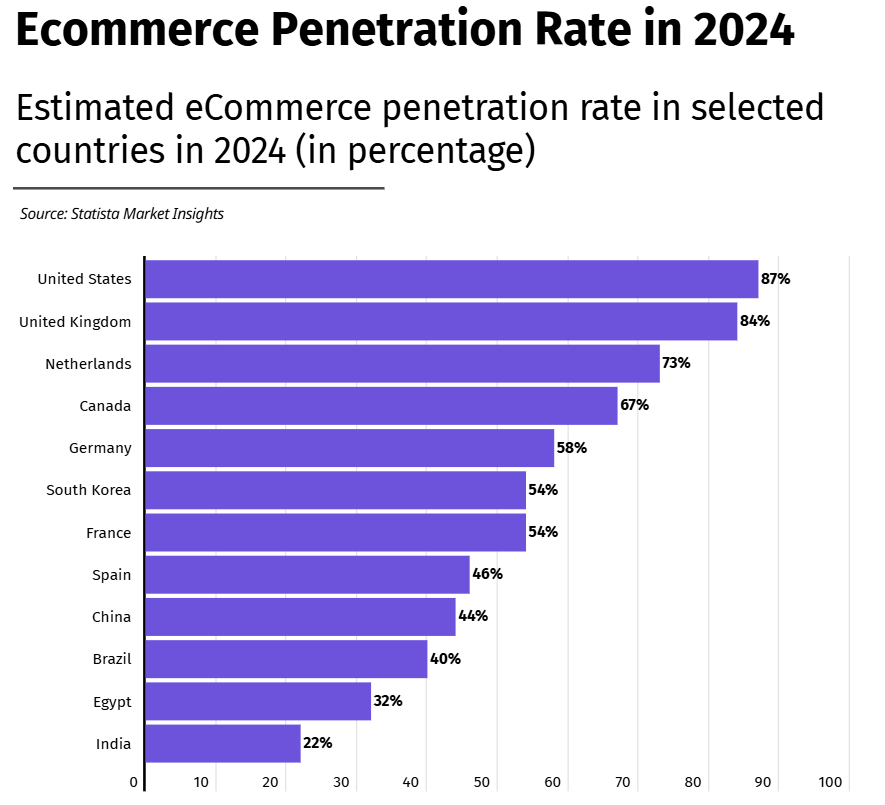

Other statistics reflect lower e-commerce penetration rates for some European countries, with the United States leading the Western world in e-commerce penetration in 2024 (Stocklytics, 2024). In the U.S., this rate was estimated at 87% for 2024, followed by the United Kingdom (84%) and the Netherlands (73%).

In China, the e-commerce penetration rate stood at 44% in 2024. In other words, nearly half of the Chinese population has yet to engage with (the transactional side of) the internet.

Amazon has achieved significant success in many Western countries, resulting in a dominant market share. However, its story is not universally one of triumph. In 2004, Amazon acquired Joyo, which it described at the time as China’s largest online retailer of books, music, and videos (Amazon, 2004) Rebrandings followed in 2007 and 2011, but these efforts proved futile. Amazon failed to outmaneuver local competitors such as Alibaba, JD.com, and Pinduoduo. Articles point to factors such as faster and cheaper shipping offered by competitors and Amazon’s minimum order value policy, which was either lower or nonexistent among rivals.

In April 2019, Amazon decided to discontinue its marketplace operations in China. However, it continued to facilitate international services for its Chinese third-party sellers, and Chinese consumers can still place international orders.

In South America, Amazon has similarly struggled to outpace competitors in certain countries. MercadoLibre, for instance, dominates in markets like Argentina and Brazil, bolstered by its established (partner) network for last-mile delivery and the growing distribution of its payment system, Mercado Pago, which continues to yield benefits.

Additionally, there are players that, while small on a global scale, rank among the largest in their regions. Examples include Zalando in Germany (Europe), and Bol.com and Coolblue in the Netherlands and Belgium. Bol.com, for instance, serves 13.7 million active customers in these countries and offers a range of 41 million items through 47,000 selling partners (as of December 31, 2024) (Bol.com, 2025). In 2024, Bol.com generated €3.1 billion in revenue. Coolblue, active in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany, achieved a turnover of €2.5 billion in FY2024 (Coolblue, 2025).

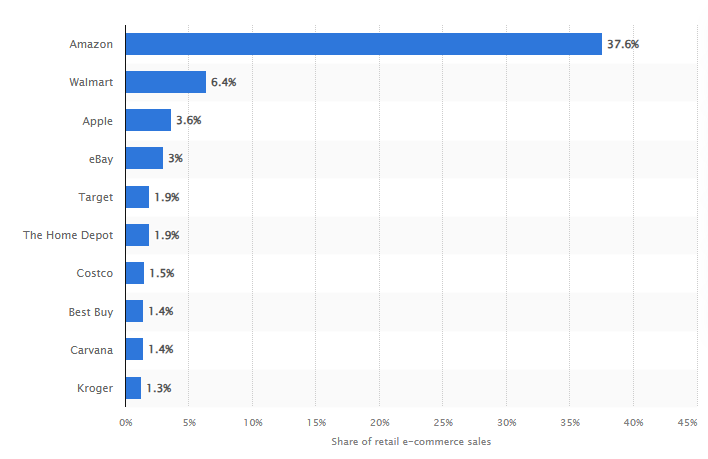

According to Statista (2025), Amazon holds a 37.8% share of the total e-commerce market in the United States. Walmart follows in second place with 6.4%, and Apple ranks third with 3.6%. This underscores the substantial lead Amazon maintains over other major players and the market as a whole.

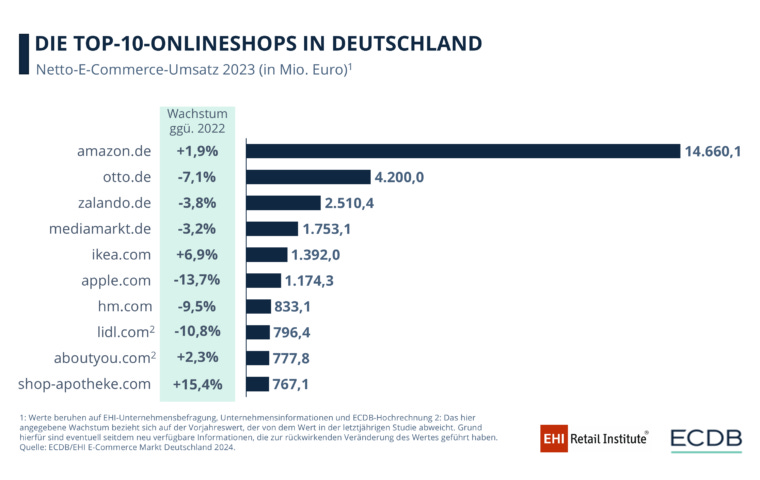

In Germany—one of Amazon’s key markets alongside the U.S./Canada, Japan, and the UK—the marketplace held a 56% share of the e-commerce market in 2023 (ECDB, 2023).

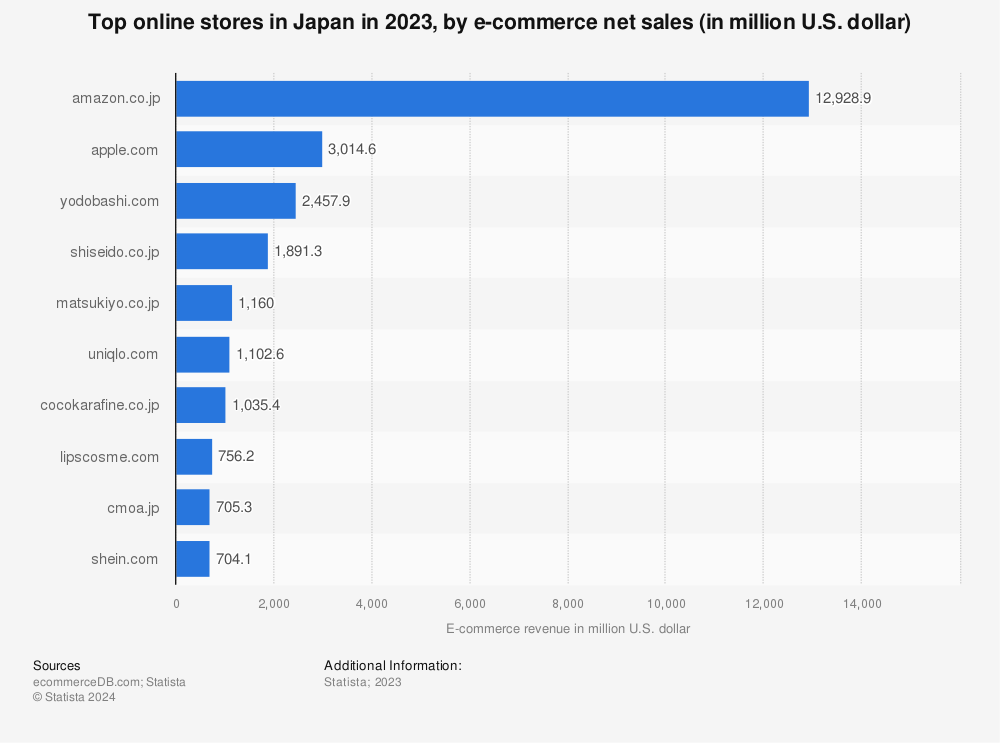

The graph above illustrates Amazon’s position among the largest online retailers in Germany. Amazon also has a dominant presence in the United Kingdom and Japan.

Conclusion

The above provides an overview of the current state of e-commerce in Amazon’s largest sales markets. Whether Amazon can maintain this position will be explored in the subsequent sections of this Deep Dive, including the chapter on Risks & Opportunities.

Streaming

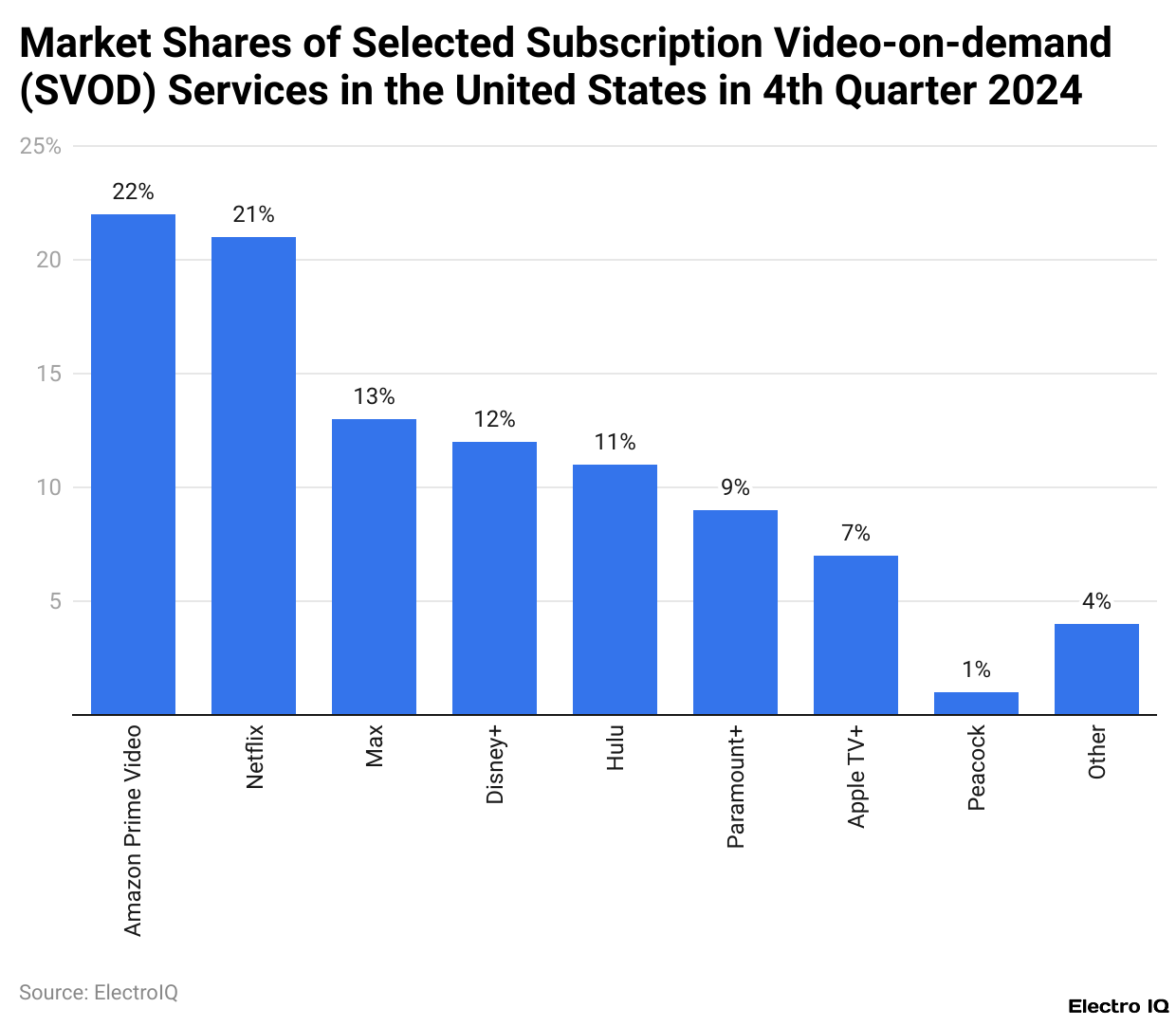

According to Statista (2025), Amazon Prime Video held a 22% market share in the Selected Subscription Video-on-Demand market in the United States in Q4 2024. It was followed by Netflix (21%) in second place and HBO Max (13%) in third.

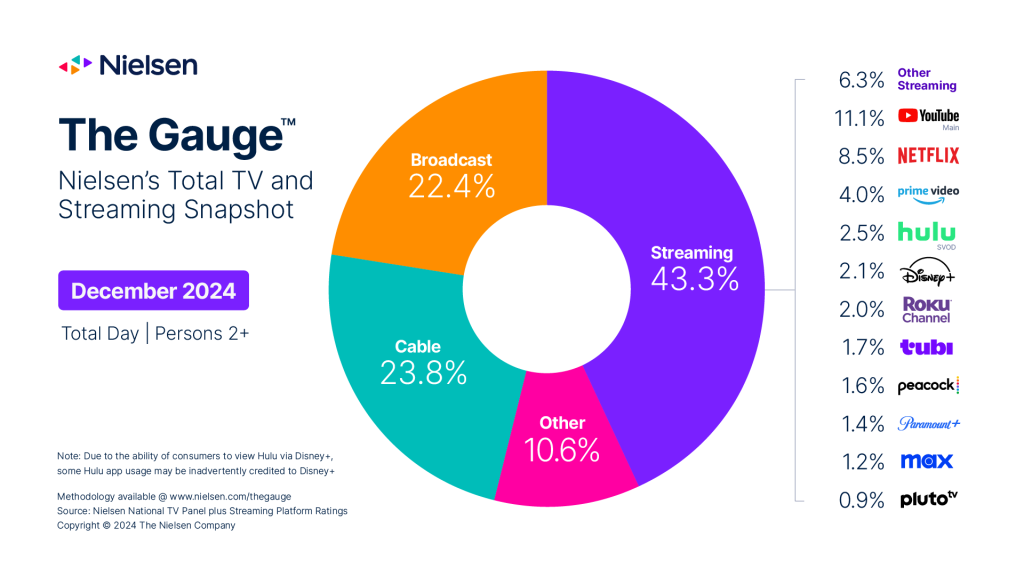

Other sources present a different perspective, including Nielsen (2025). In this study, Amazon Prime Video recorded a 4% market share in December 2024 in the United States. However, this percentage reflects its estimated share of the total TV market.

In Nielsen’s research, competing streamers YouTube (11.1%) and Netflix (8.5%) ranked above Amazon Prime Video. It should be noted that this represents an estimated “market share” over a one-month period only.

Conclusion

Like the e-commerce sector, the streaming industry is experiencing a positive secular growth trend: the market share of streaming continues to rise relative to broadcast and cable. Streaming’s share increased from 19% at the end of 2019 to 43.3% over five years. The pandemic period accelerated this growth, but streaming’s market share continued to climb steadily even after the pandemic subsided.

Cloud

Amazon gained an early lead in the cloud sector with AWS, a market it helped shape. This advantage was extended as competitors Microsoft and Google only began broadly rolling out their commercial services in 2010 and 2012, respectively. Jeff Bezos described this as a “miracle”:

And then a business miracle happened; this never happens—the greatest piece of business luck in the history of business, so far as I know. We faced no like-minded competition for 7 years. It’s unbelievable. [...] When I launched Amazon.com in 1995, Barnes & Noble then launched Barnesandnoble.com in 1997. Two years later is very typical if you invent something new. We launched Kindle; Barnes & Noble launched Nook two years later. We launched Echo; Google launched Google Home two years later. When you pioneer, if you’re lucky, you get a two-year head start. Nobody gets a seven-year head start, and so that was incredible.

— Jeff Bezos (Youtube, 2018)

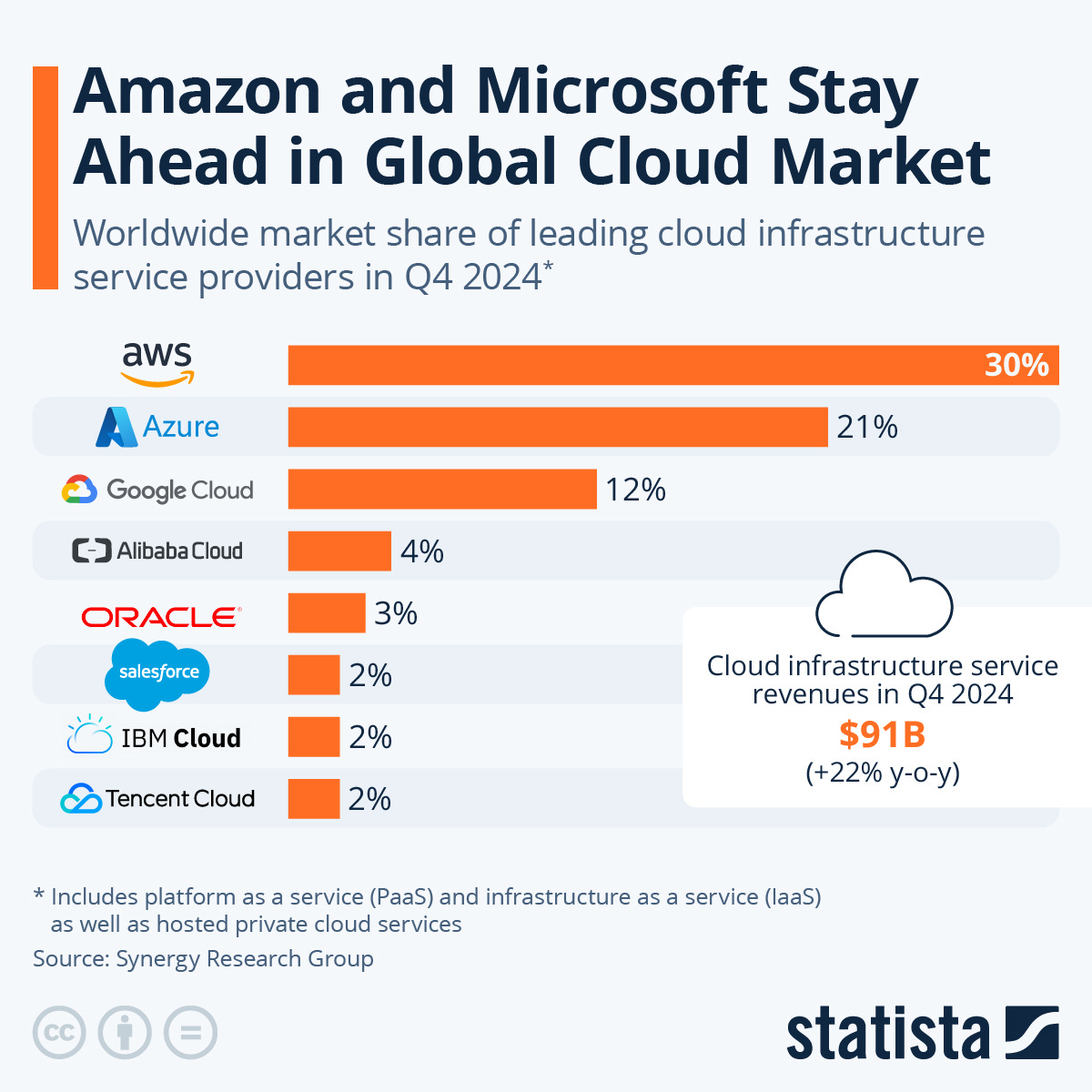

According to Statista (2024), Amazon held a 30% share of the global cloud market as of Q4 2024. Microsoft (Azure) accounted for 21%, while Google held 12%. It should be noted that Microsoft’s share includes revenue streams beyond pure cloud services.

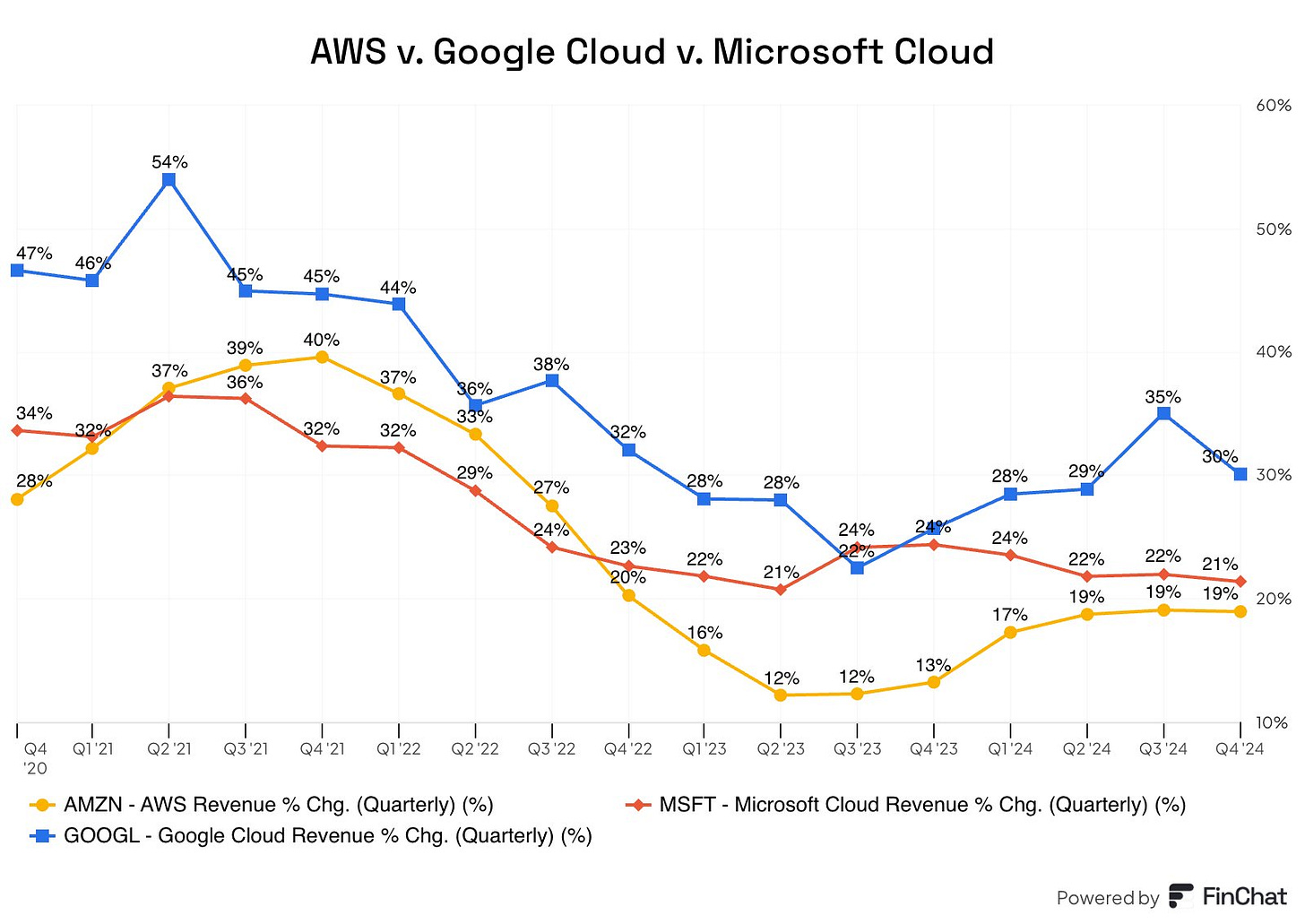

Since Q3 2022, the reported cloud revenue growth rates of Microsoft and Google have outpaced AWS, as shown in the figure below, causing AWS’s market share to decline from 34% in Q3 2022 to 30% by Q4 2024.

The figure below illustrates the year-over-year percentage growth in reported cloud revenues for AWS, Microsoft, and Google, quarterly, since Q4 2020.

As of December 31, 2024, AWS reported a backlog of $177 billion, encompassing contracts with terms exceeding one year.

Conclusion

Due to Amazon’s large scale and relatively slower growth, its estimated market share—calculated by aggregating available cloud revenues—declined by a few percentage points in recent years. However, in the most recent quarters, AWS’s revenue growth has closely tracked that of the second-ranked player, Microsoft. Consequently, in 2024, only Google’s market share increased relative to Microsoft and AWS.

In 2024, Google Cloud’s revenue rose by $10.4 billion, while AWS recorded a year-over-year revenue increase of $16.8 billion.

Chapter 4 | Financials

Revenue Streams

As outlined in the previous chapters, Amazon derives its income from multiple sources. These include selling products from its own inventory, providing a platform for third-party sellers, generating revenue from subscriptions, and earning income through its AWS services.

Typically, Amazon records the gross revenue from products sold from its own inventory as product sales (Net Product Sales, totaling $272.3 billion in FY2024), while it registers its net share of the revenue from third-party seller transactions as service sales (Net Service Sales, amounting to $365.6 billion). The latter includes revenue from subscriptions, advertising, and AWS (Amazon, AR2024 p. 20).

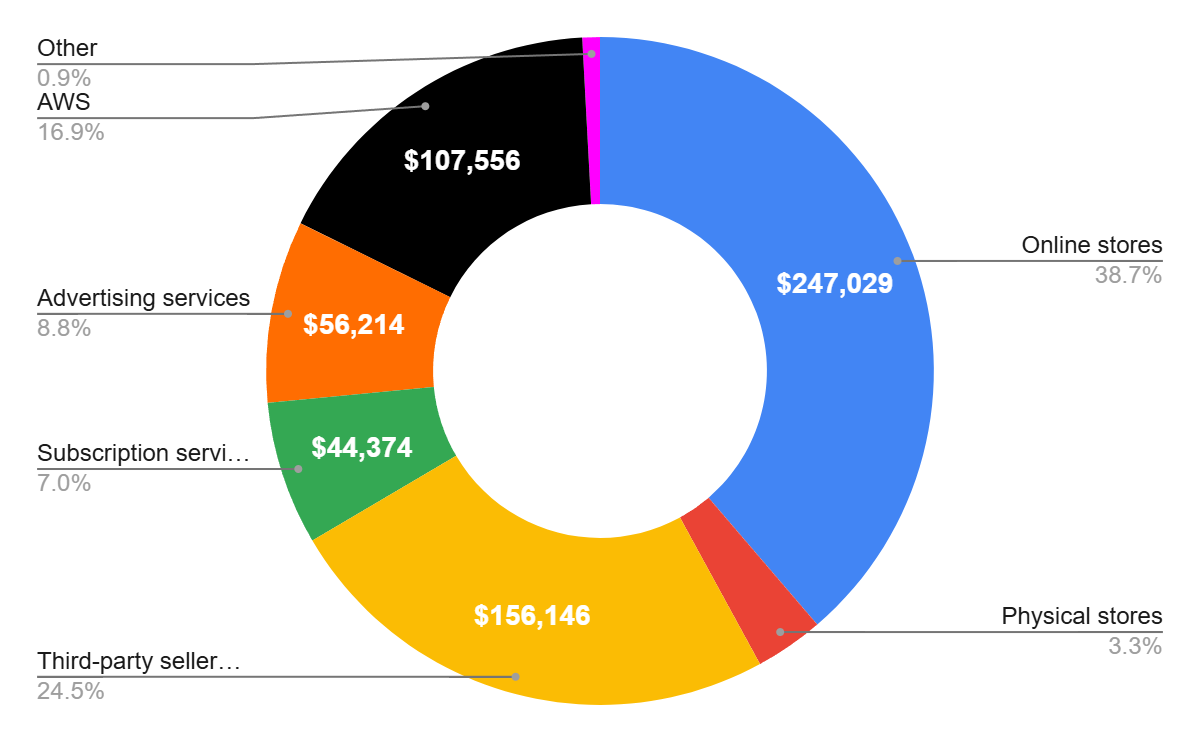

In its financial reporting, Amazon breaks down its revenue into the following seven segments (revenue for FY2024, rounded):

Online stores ($247 billion)

Physical stores ($21 billion)

Third-party seller services ($156 billion)

Subscription services ($44 billion)

Advertising services ($56 billion)

AWS ($108 billion)

Other ($5 billion)

These seven revenue streams are visually represented in the pie chart below.

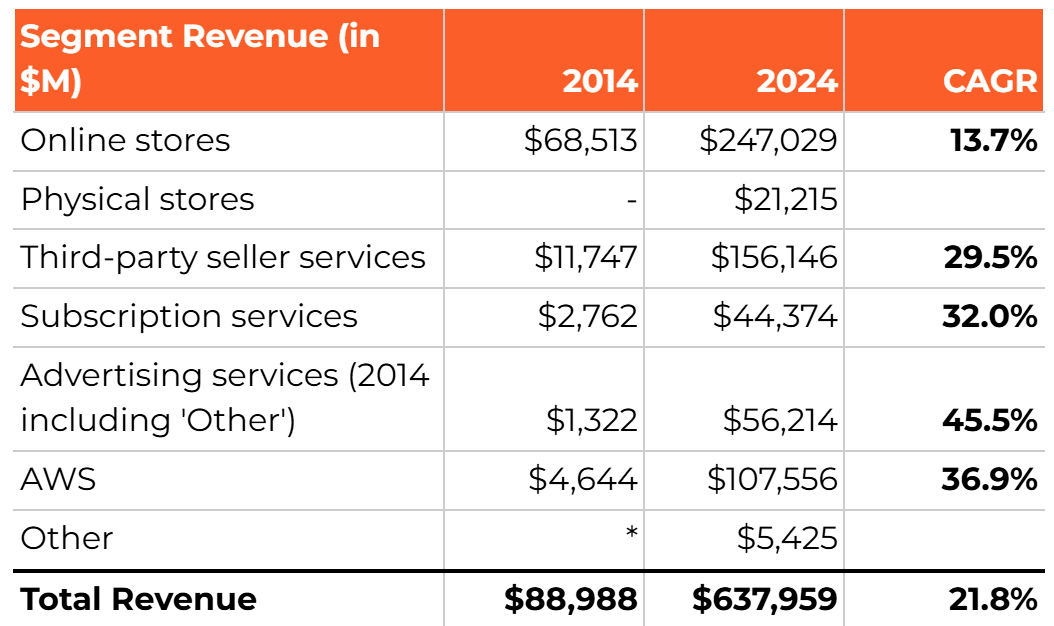

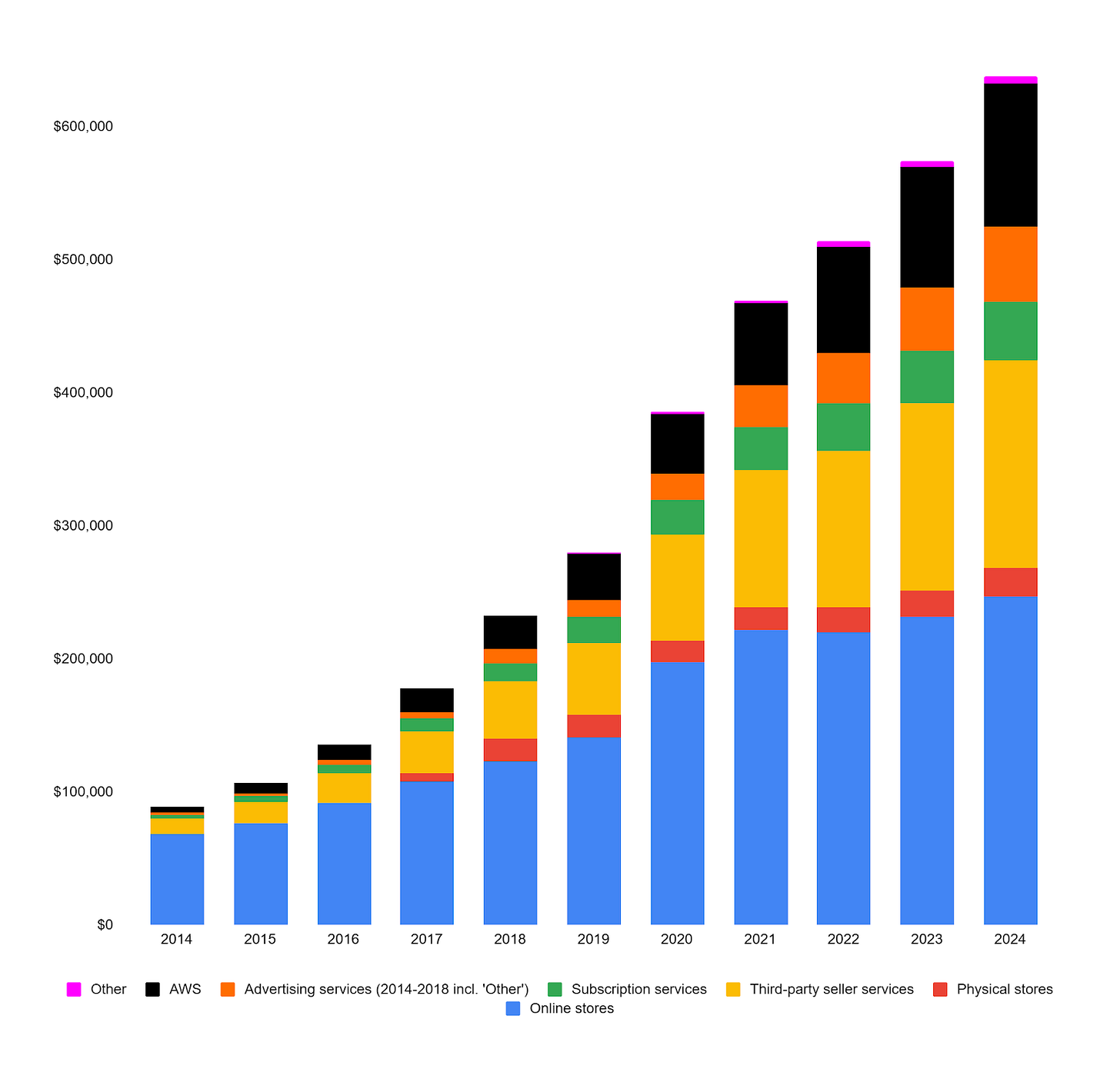

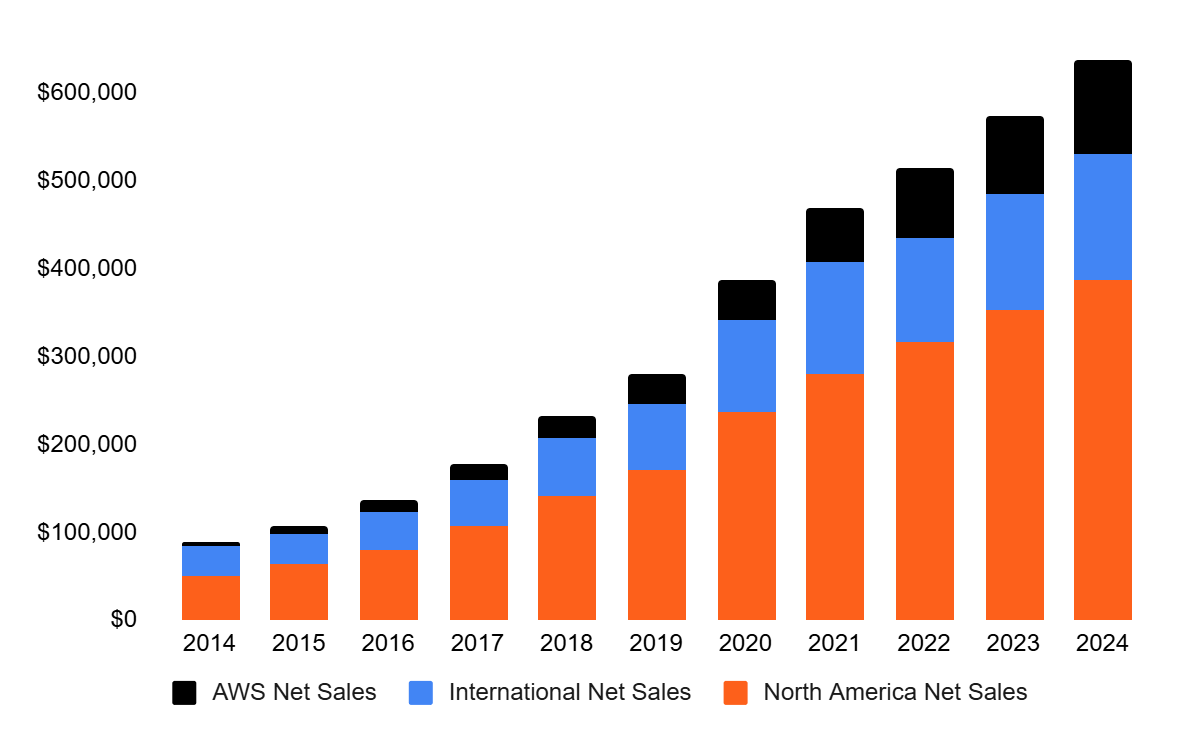

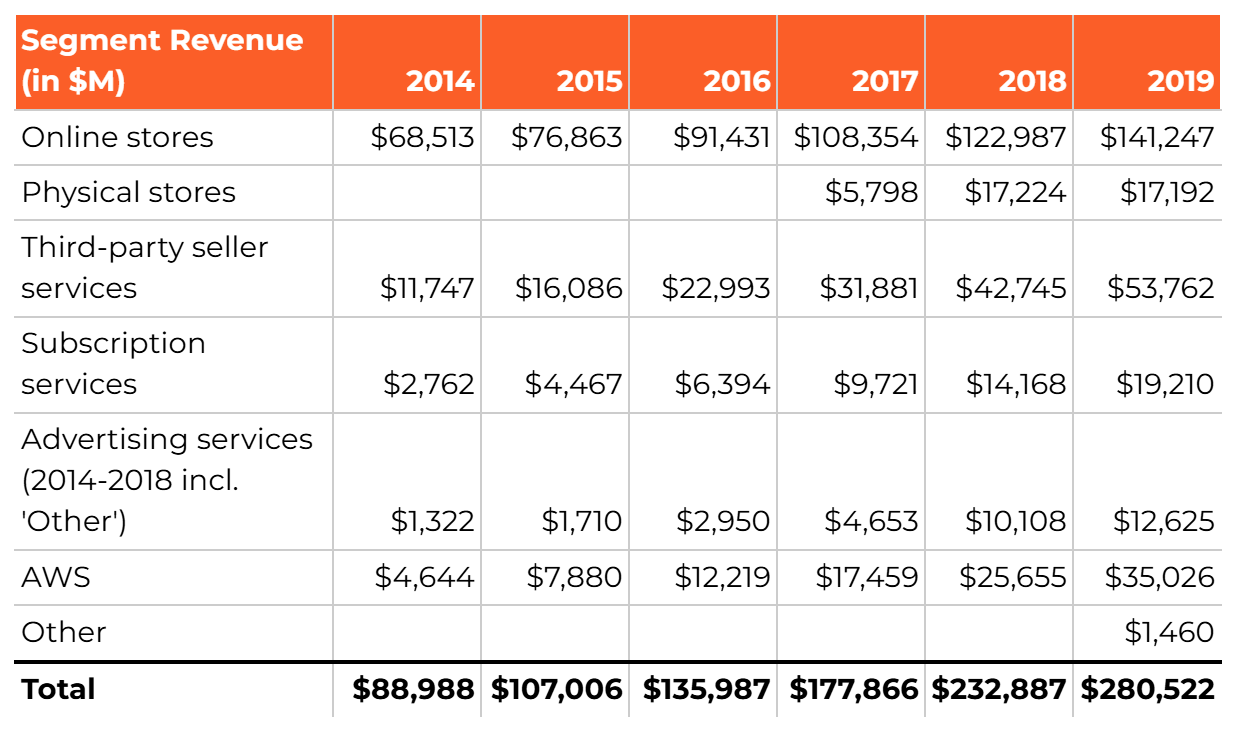

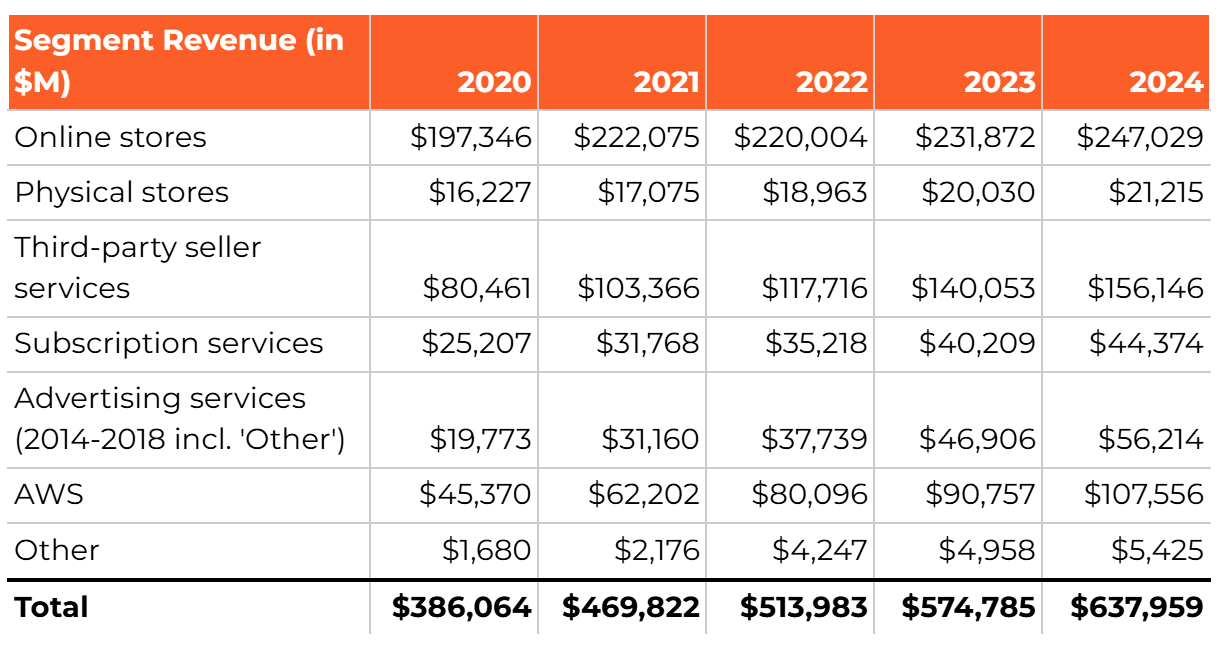

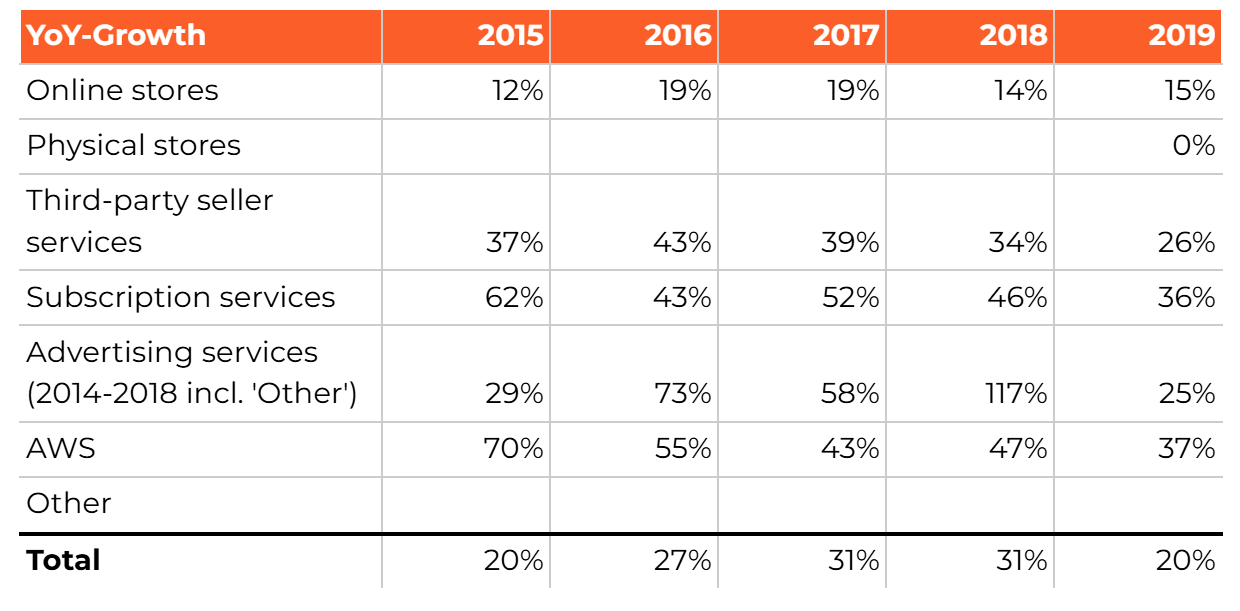

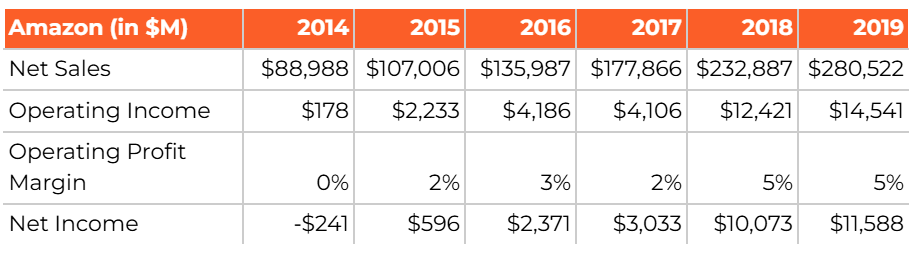

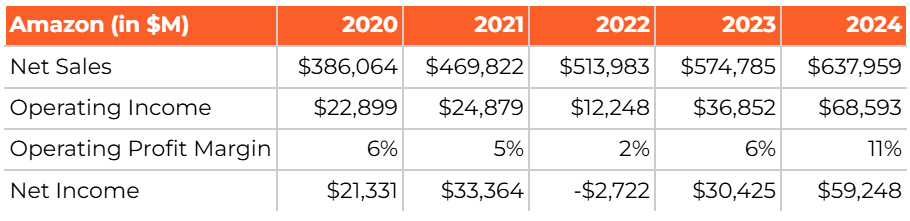

Amazon’s total revenue for fiscal year 2024 reached $638 billion, compared to $89 billion in FY2014. This reflects a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21.8%. A breakdown by segment is provided below.

Specifications regarding Amazon’s revenue from Advertising Services have been retroactively detailed in Amazon’s reports starting from FY2019; in the fiscal years prior, this advertising component was included under "Other."

Below is an overview of the development of Amazon’s individual segments over the fiscal years 2014–2024.

As illustrated above, in FY2014, the majority of Amazon’s revenue stemmed from its own sales: 77% of its revenue originated from Online Stores. By FY2024, this figure had decreased to 39%. Although Amazon’s Online Stores segment experienced the largest absolute growth in dollar terms (from $69 billion to $247 billion), the percentage growth of the other segments was significantly higher, owing to their relatively small starting base in 2014.

Amazon’s advertising division demonstrated the most substantial percentage growth in recent years, with an approximate compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 45.5% since 2014, reflecting a significant increase in advertising sales. Other segments, including AWS (36.9% CAGR), Subscription Services (32% CAGR), and Third-party Seller Services (29.5% CAGR), also expanded at a rapid pace. Over the past decade, Amazon’s annual revenues from Third-party Seller Services and AWS grew by $144 billion and $103 billion, respectively.

Amazon’s Operating Leverage

Amazon focuses on reducing variable costs per unit by leveraging its fixed cost structure. Its variable costs include the procurement and cost of goods sold for products and content, as well as direct costs associated with sales, such as variable logistics and transaction expenses.

To lower its variable costs per unit, Amazon employs strategies such as direct sourcing, enhancing purchasing advantages with suppliers, and eliminating inefficiencies in its operational processes.

Amazon’s fixed costs primarily consist of investments in infrastructure, encompassing both the data centers supporting AWS and the logistics and distribution centers for its (online) stores. To a lesser extent, these costs also include the production of digital content for its Amazon Prime Video offerings (Amazon, AR2024, p. 20).

Operating Profit

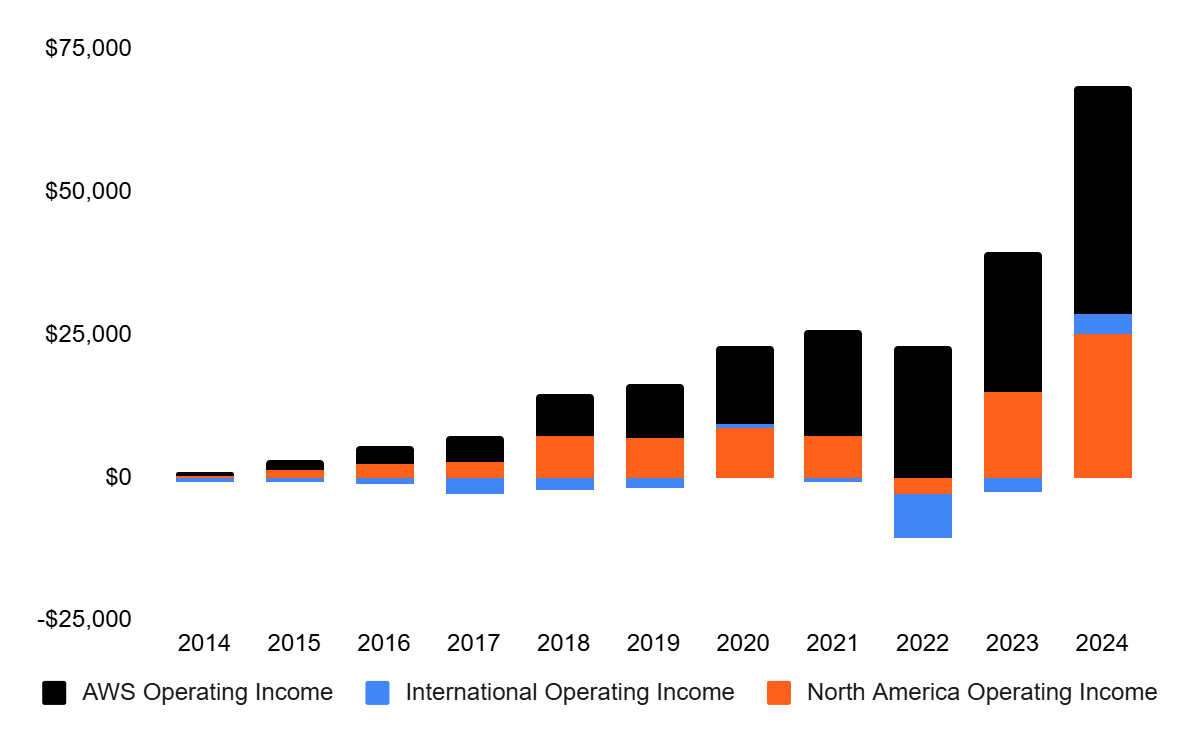

In terms of operating profitability, Amazon’s reporting distinguishes between the following three segments:

North America

International

Amazon Web Services

Amazon Web Services (AWS) corresponds to the same segment detailed earlier, while all other revenues are now categorized by region rather than segment: North America (United States, Canada, and Mexico) versus all other international countries where Amazon operates.

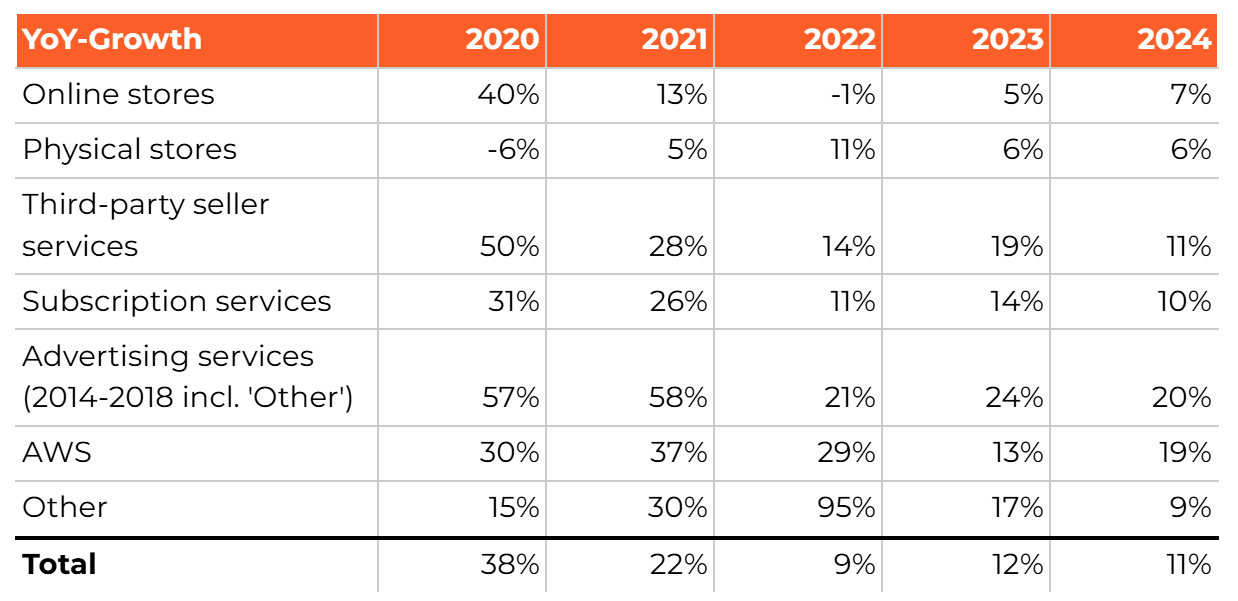

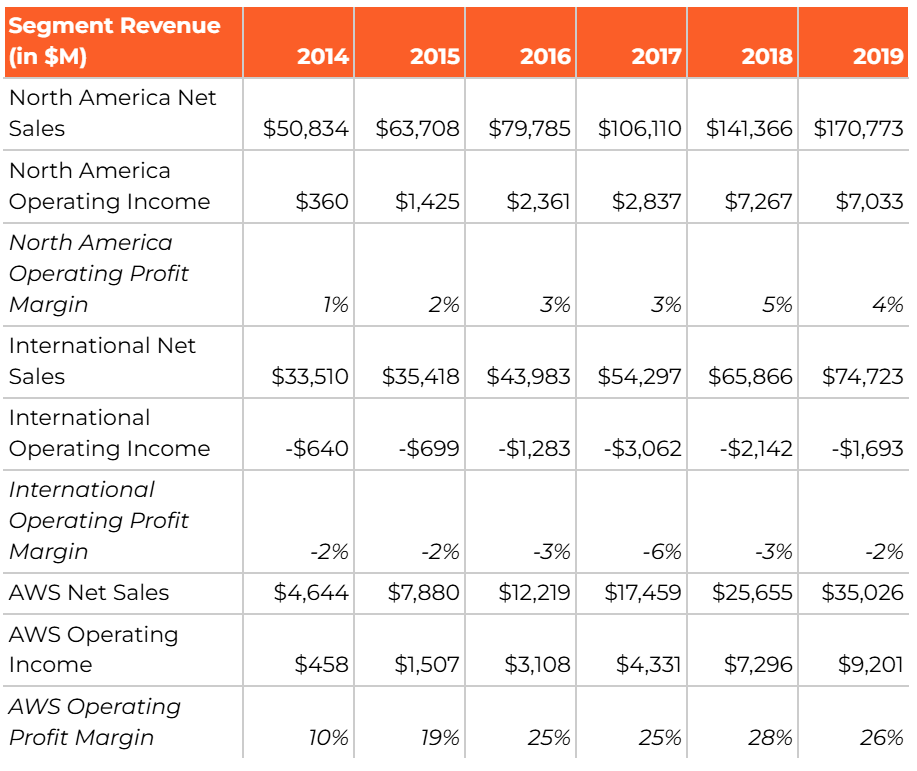

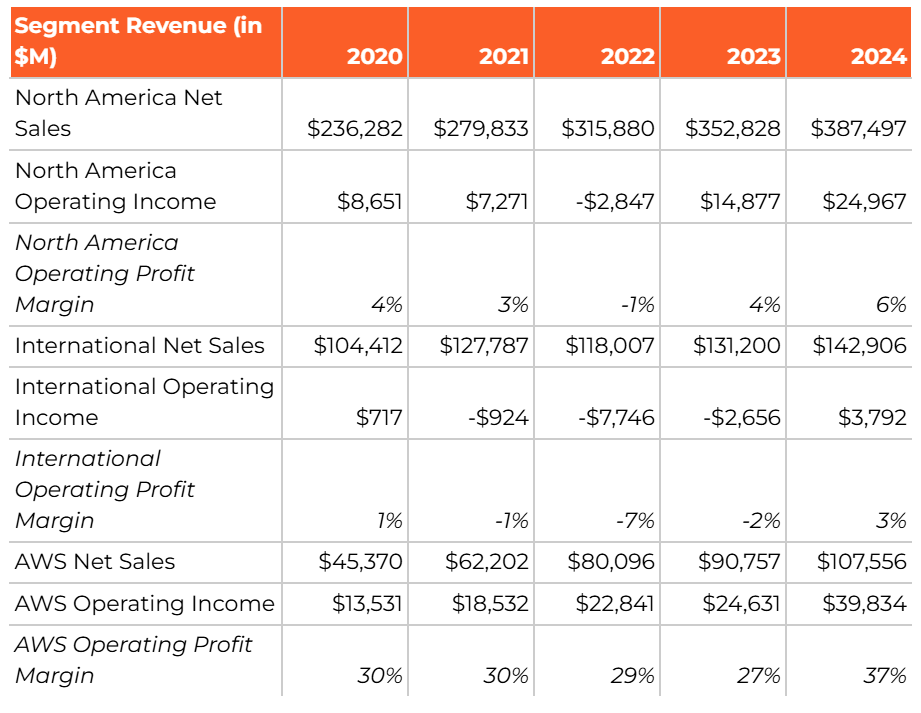

Below is an overview of the revenue development for these three segments, alongside the evolution of operating profitability as reported by Amazon.

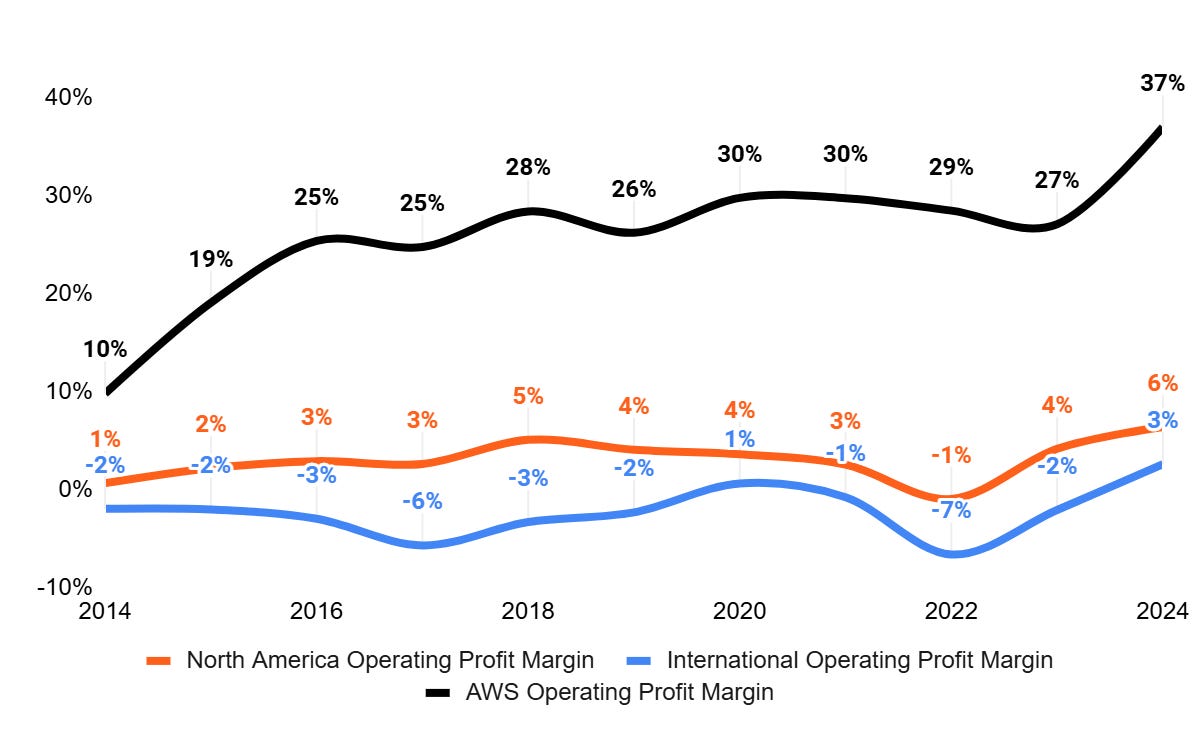

To express the operating profit of these 3 segments as a percentage of their respective revenues, the following overview illustrates the development of operating profit margins over the period 2014-2024.

Amazon Web Services

The operating profitability of AWS has risen over the past decade, increasing from 10% in 2014 to 37% in 2024. In FY2024, AWS achieved an operating profit of $39.8 billion on revenue of $107.6 billion, compared to an operating profit of $458 million on revenue of $4.6 billion in FY2014.

The basis for Amazon’s year-over-year increase in 2024 stems not only from enhanced profitability, but also, in part, from an adjustment to the estimated economic life of AWS servers. Effective January 2024, this was extended from 5 to 6 years, resulting in an artificial 200 basis point increase in the operating profit margin for Q4 2024, according to Amazon (Q4 2024 Earnings Call).

However, as of January 1, 2025, Amazon reverted the estimated life for a portion of its servers and networking equipment back to 5 years, which is expected to reduce operating profit by approximately $700 million in FY2025. Additionally, the company accelerated depreciation by about $920 million on certain servers and networking equipment, with an additional estimated $600 million in accelerated depreciation anticipated in 2025.

Amazon attributes this adjustment to the accelerating pace of technological advancement, particularly in AI and machine learning.

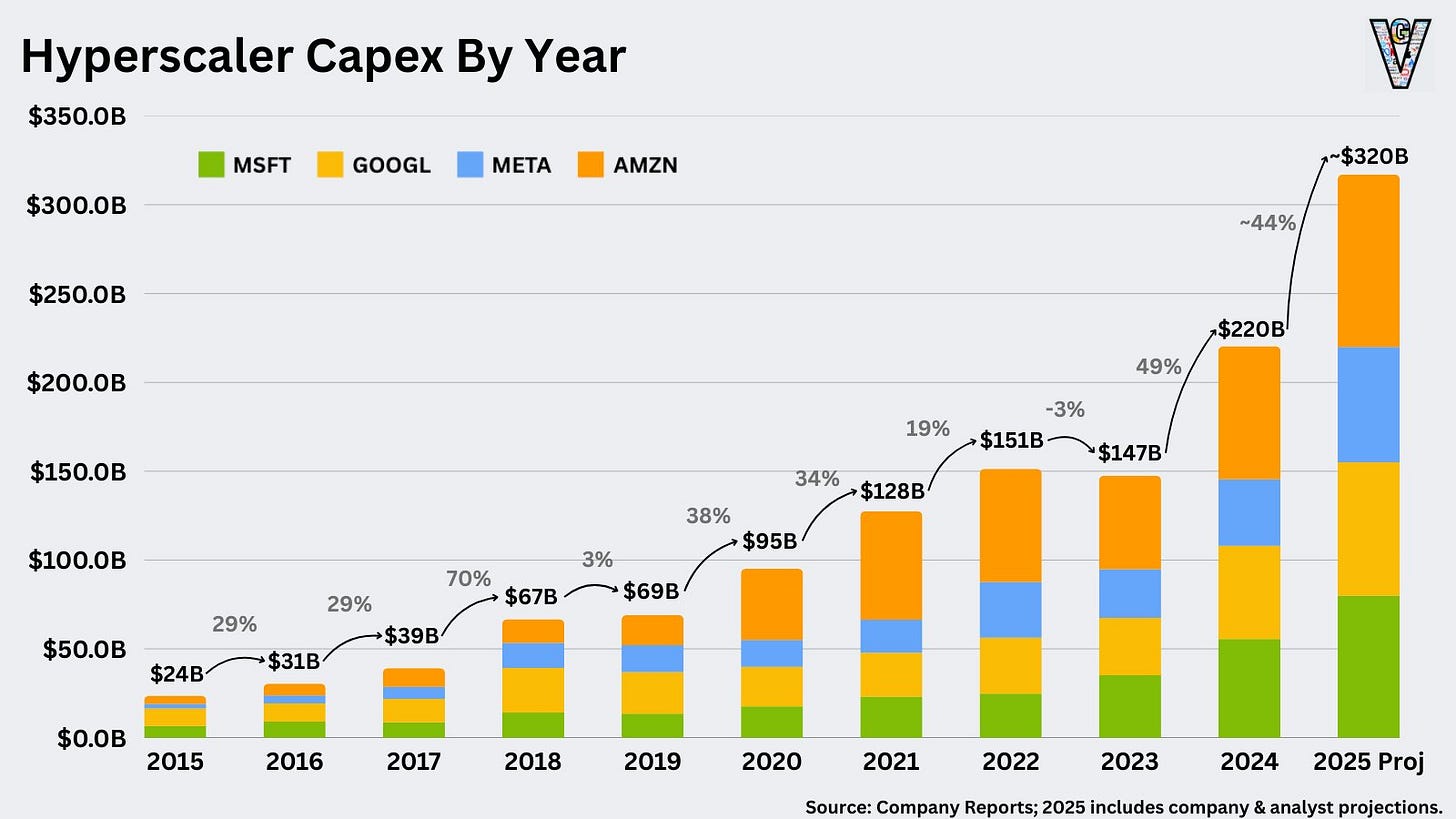

For FY2025, Amazon anticipates capital expenditures (CAPEX) exceeding $100 billion. This investment is deemed necessary to meet the significant demand for (and facilitation of) AI services.

[...] the way that AWS business works and the way the cash cycle works is that the faster we grow, the more capex we end up spending because we have to procure data center and hardware and chips and networking gear ahead of when we're able to monetize it. We don't procure it unless we see significant signals of demand. And so, when AWS is expanding its capex, particularly in what we think is one of these once-in-a-lifetime type of business opportunities like AI represents, I think it's actually quite a good sign, medium to long term, for the AWS business. And I actually think that spending this capital to pursue this opportunity, which from our perspective, we think virtually every application that we know of today is going to be reinvented with AI inside of it and with inference being a core building block, just like compute and storage and database.

— Andy Jassy (CEO Amazon)

North America

The operating profitability of the North America region increased from a 1% operating margin in FY2014 to 6% in FY2024. This reflects the benefits Amazon has reaped from its expanded scale. The fixed costs—stemming from capital-intensive investments made since its inception and ongoing commitments—are offset by higher sales volumes, resulting in lower variable costs per unit.

Additionally, a shift in Amazon’s sales mix has contributed to improved operating profitability. The growing proportion of revenue from Third-party Seller Services, Advertising Services, and Subscription Services—relative to Amazon’s Online Stores and Physical Stores—has positively impacted the operating profit margin.

International

A similar trend applies to Amazon’s international operations, where the operating profit margin rose from -2% in 2014 to +3% in FY2024. Like the North America segment, this improvement highlights the initial advantages Amazon is beginning to realize from its operating leverage in its international markets.

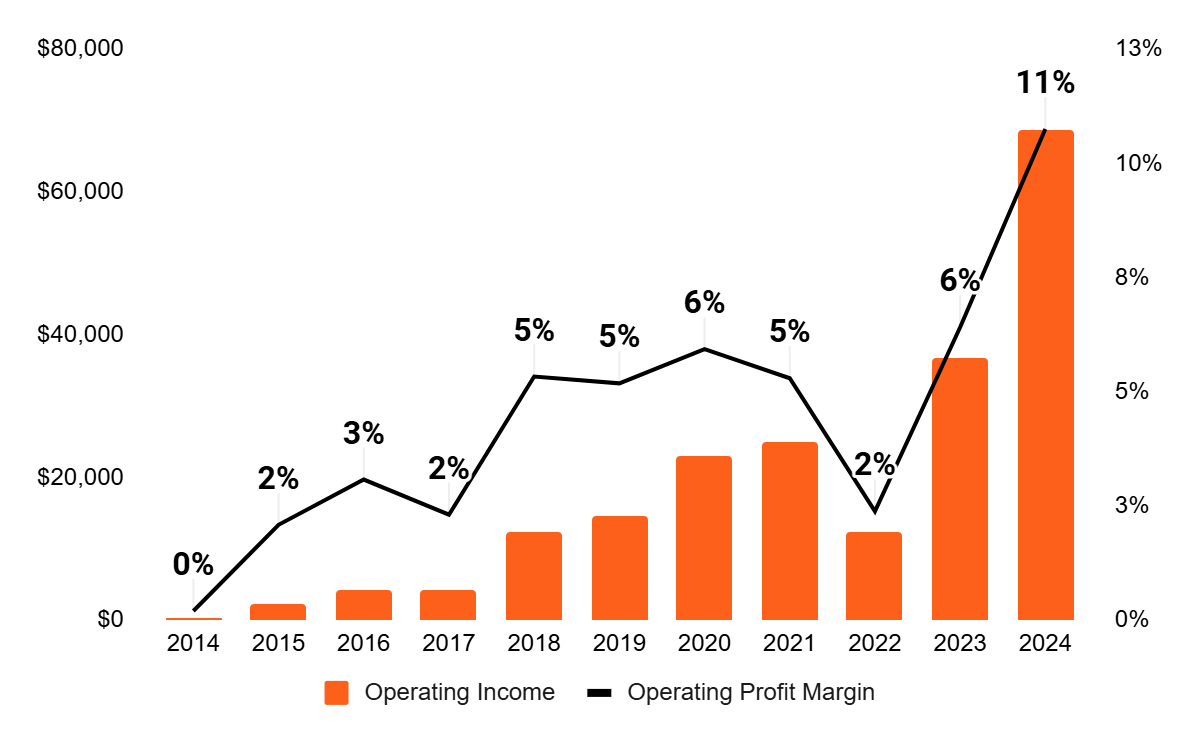

Development 2014-2024

Below is a representation of Amazon’s total operating profit as a company for each year (in orange), alongside this operating profit as a percentage of the company’s total revenue (in black).

Follow the money: Cash flow analysis

Why focus on cash flows? Because a share of stock is a share of a company’s future cash flows, and, as a result, cash flows more than any other single variable seem to do the best job of explaining a company’s stock price over the long term.

— Jeff Bezos (Shareholder Letter, 2001)

In the quote above—which perfectly encapsulates the essence of investing—Jeff Bezos reflected on his 1997 letter to shareholders:

When forced to choose between optimizing the appearance of our GAAP accounting and maximizing the present value of future cash flows, we’ll take the cash flows.

— Jeff Bezos (Shareholder Letter, 1997)

This statement immediately highlights Bezos’ long-term mindset back in 1997, prioritizing the development of cash flows in the (distant) future over short-term accounting profits.

Amazon’s focus, therefore, lies in the long-term, sustainable growth of its cash flows. These cash flows are primarily driven by an increase in Amazon’s operating income and the efficient management of its working capital, with capital expenditures (CAPEX) serving as the bridge between its cash flows from operating activities and its free cash flows.

To boost revenue, Amazon concentrates on all aspects of customer experience, including lowering prices, enhancing its product offerings, and delivering faster, higher-quality shipments (via its e-commerce platform) and services (via AWS). This strategy aims to elevate the customer experience and, consequently, foster customer trust (Amazon, AR2024, p. 20). A flywheel in motion.

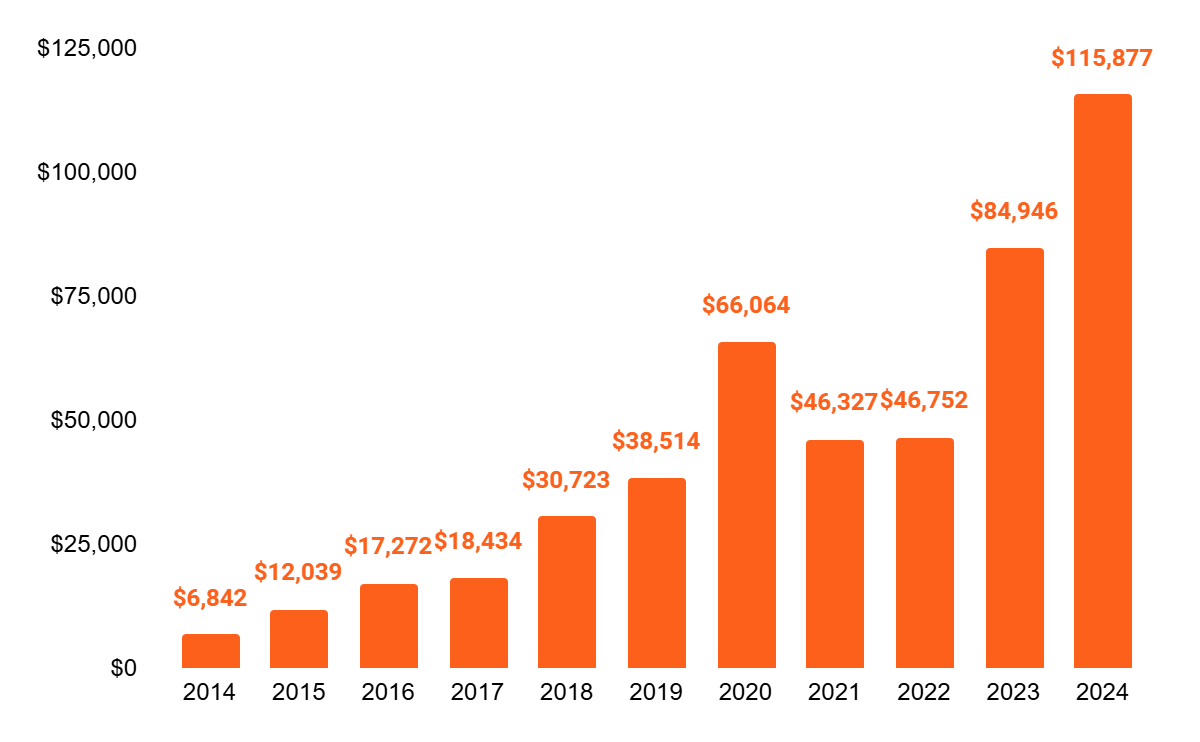

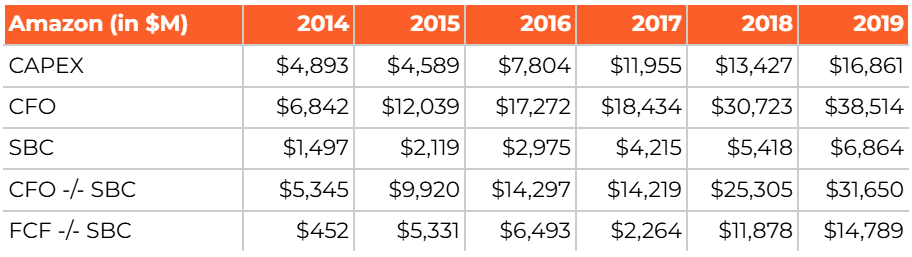

The figure below illustrates the development of Amazon’s cash flow from operating activities, which grew from $6.8 billion in 2014 to $115.9 billion in FY2024—a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 32.7%.

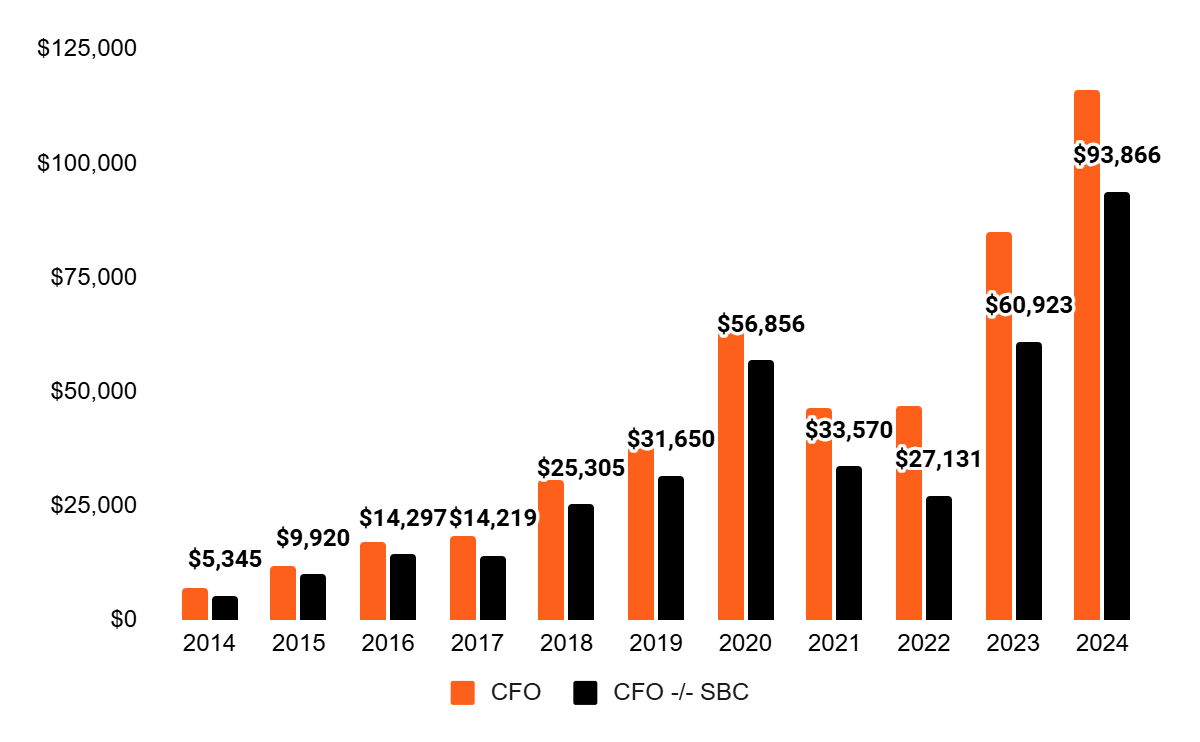

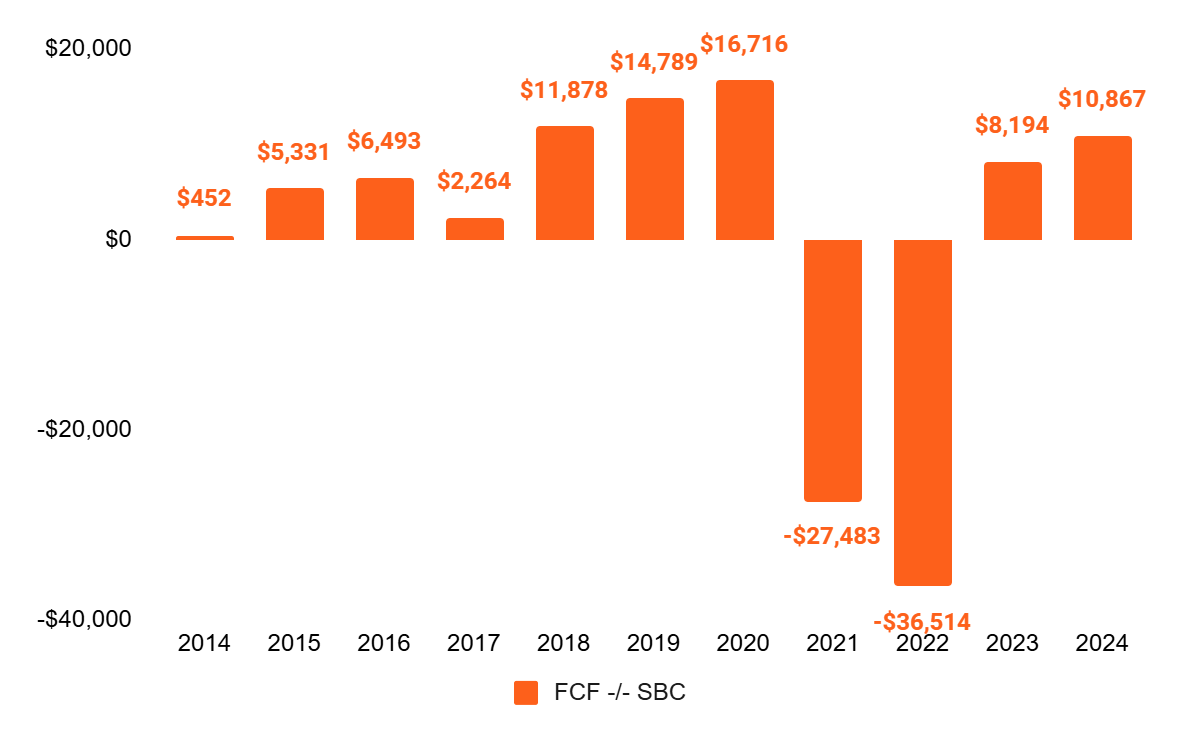

Over FY2024, Amazon recorded a total of $22 billion in stock-based compensation (SBC). In its cash flow statement, Amazon adjusts for this amount, as it does not represent direct cash outflows. However, this adjustment can distort the picture, as the dilution of outstanding shares results in a lower free cash flow (FCF) per share for existing shareholders.

The graph below depicts Amazon’s cash flow from operating activities (in orange) alongside a corrected version accounting for stock-based compensation (in black).

Amazon’s cash flow from operating activities -/- SBC increased at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 33.2% since 2014.

CAPEX

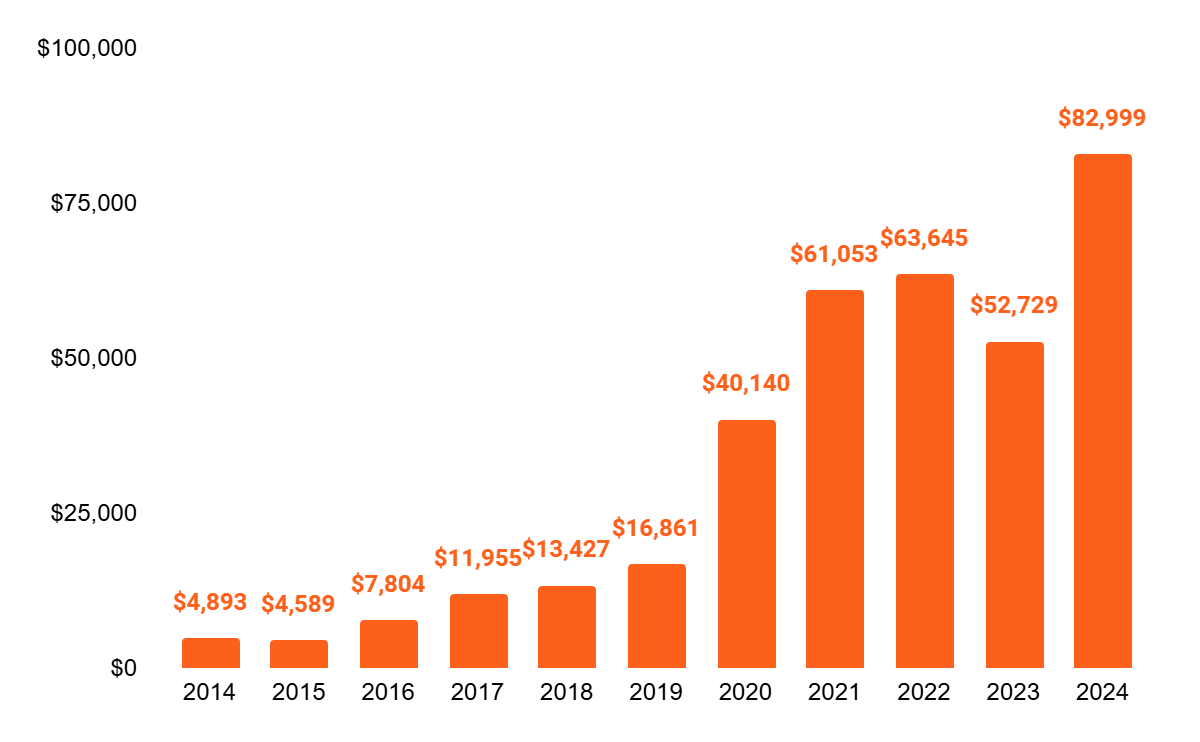

Below is an overview of Amazon’s capital expenditure (CAPEX) investments since 2014. While the company’s CAPEX stood at $4.9 billion in 2014, it reached $83 billion in the most recent fiscal year, 2024.

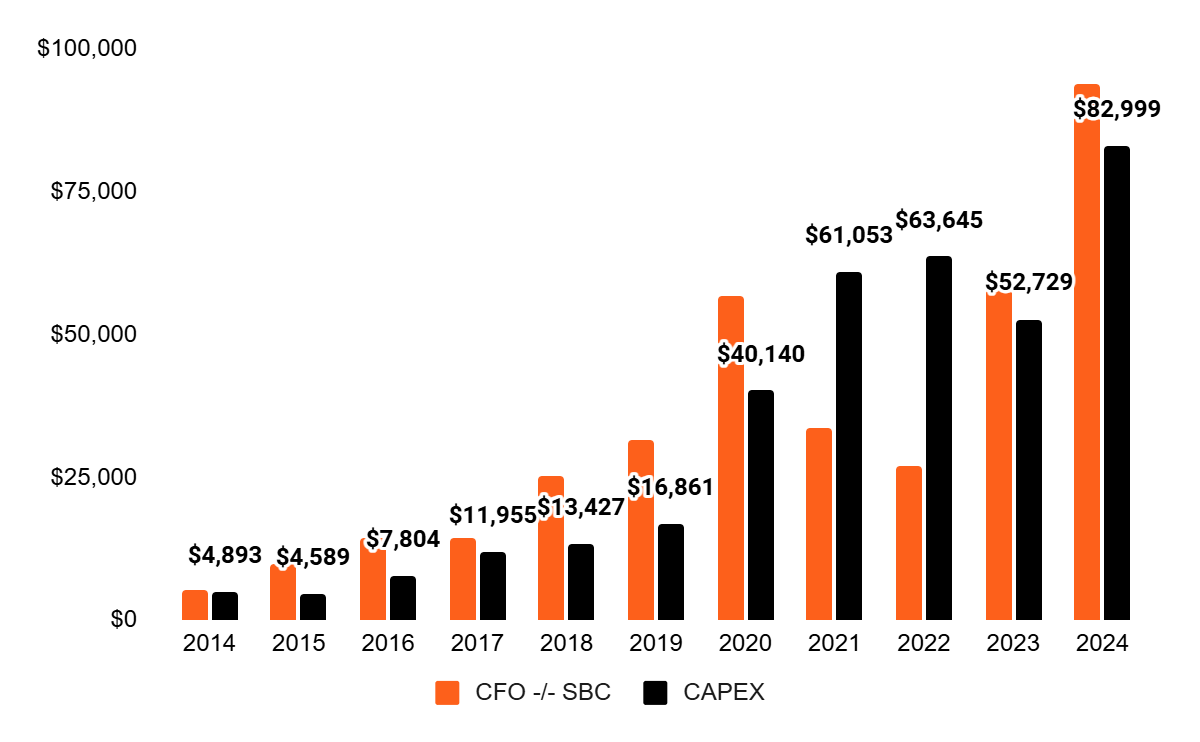

To complete the comparison, the development of Amazon’s cash flow from operating activities -/- SBC alongside its CAPEX investments is presented below.

From 2014 to 2020, Amazon’s cash flow from operating activities (adjusted for SBC) exceeded its CAPEX investments each year. Since 2021, however, it is evident that Amazon has been investing heavily: over the past four years (2021–2024), its cumulative CAPEX investments totaled $260 billion. The majority of this has been directed toward AWS to expand capacity and develop AI services. For FY2025, Amazon anticipates CAPEX investments exceeding $100 billion.

Consequently, Amazon’s FCF (adjusted for SBC) has been significantly suppressed, as illustrated in the graph below.

In my view, the graph above speaks volumes: Amazon consistently places its focus on the future. Investments made in the past are now generating the capital available for projects aimed at securing future returns.

Balance Sheet

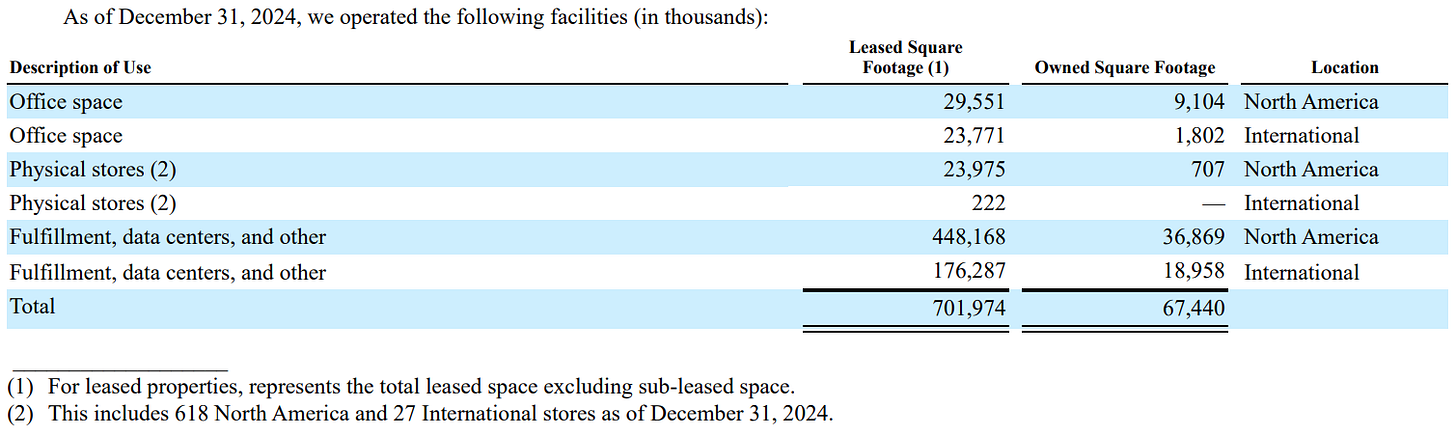

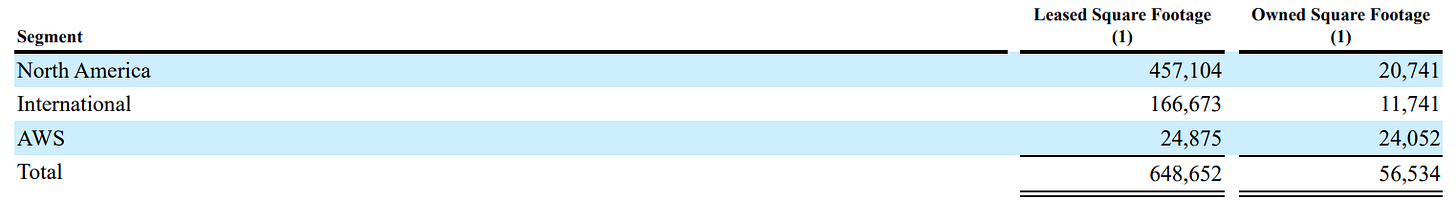

Assets

The majority of Amazon’s offices, stores, and distribution and data centers are leased. Out of a total of 769,414 square feet, 701,974 square feet are leased, as detailed in the table below.

Excluding offices, 68% of Amazon’s square footage is located in North America.

On Amazon’s balance sheet (as of December 31, 2024), Property and Equipment is valued at $252.7 billion. This includes owned (non-leased) offices, stores, and distribution and data centers ($123 billion gross), as well as the book value of Amazon’s servers and networking equipment ($219 billion gross). Given the substantial investments in recent years, a significant portion of this $252.7 billion pertains to the latter.

Additionally, Amazon holds $101 billion in cash (Cash and Cash Equivalents) and short-term marketable securities, and $34 billion in inventory. Goodwill is recorded at $23 billion. Including other items, Amazon’s total assets as of December 31, 2024, amounted to $625 billion.

Liabilities & Equity

Offsetting these assets are $53 billion in long-term debt, $94 billion in accounts payable, and $78 billion in long-term lease obligations (on the asset side, operational leases are valued at $76 billion).

The majority of Amazon’s liabilities & equity is comprised of equity: as of December 31, 2024, Stockholders’ Equity stood at $286 billion.

Currently, Amazon’s market capitalization is $2,000 billion. This indicates that the market values Amazon’s assets—and the returns they are expected to generate in the future—at a premium. Whether I believe this is justified is discussed in the Valuation chapter.

Below, Amazon’s financial key performance indicators (KPIs) for recent years are presented.

Financial Data Amazon — Profit & Loss Statement

Financial Data Amazon — Cash Flow Statement

Financial Data Amazon — Ratio’s

Sources: Amazon Annual Reports 2014-2024.

Chapter 5 | Culture & Management

Amazon’s Employees: Amazonians

As of December 31, 2024, the entire Amazon conglomerate employed 1,556,000 full-time and part-time workers, or, as they refer to themselves, "Amazonians." With a market capitalization of approximately $2 trillion, this equates to a valuation of roughly $1.3 million per employee. This figure excludes robots—Amazon utilized more than 750,000 robots in 2023 (Amazon, 2025; 2023).

Amazon describes its approach to Human Capital as follows:

We strive to be Earth’s best employer. We rely on numerous and evolving initiatives to implement this objective and invent mechanisms for talent development, including competitive pay and benefits, flexible work arrangements, and skills training and educational programs [...].

— Amazon Annual Report FY2024

Employees rate Amazon 3.6 out of 5 on Glassdoor (2025), with 65% of workers indicating they would recommend working at Amazon to a friend (Glassdoor, 2025).

Amazon’s Leadership Principles

As Amazon grew, Jeff Bezos and his team initially established 9 Leadership Principles, accompanied by a broad set of methodologies intended to strengthen the company’s culture. Today, this has expanded to 16 principles, against which every job applicant at Amazon is evaluated. Amazon describes these principles as follows:

[Amazon’s Leadership Principles] are a guiding set of tenets which Amazon employees use every day to move forward in situations, solve problems, deal with conflict, and make decisions. [...] They are the building blocks of culture at Amazon; they set the standard for how we should work with each other as a group of employees and they maintain standards and consistency across our many functions and geographies. The Leadership Principles allow us to interact with each other or approach problems with the same mindset and expectations. They have been integral for scaling growth successfully.

— Liz Jones (Amazon, 2023)

Below, these 16 Leadership Principles are listed (Amazon, 2025).

1) Customer Obsession

Leaders start with the customer and work backwards. They work vigorously to earn and keep customer trust. Although leaders pay attention to competitors, they obsess over customers.

2) Ownership

Leaders are owners. They think long term and don’t sacrifice long-term value for short-term results. They act on behalf of the entire company, beyond just their own team. They never say “that’s not my job.”

3) Invent and Simplify

Leaders expect and require innovation and invention from their teams and always find ways to simplify. They are externally aware, look for new ideas from everywhere, and are not limited by “not invented here.” As we do new things, we accept that we may be misunderstood for long periods of time.

4) Are Right, A Lot

Leaders are right a lot. They have strong judgment and good instincts. They seek diverse perspectives and work to disconfirm their beliefs.

5) Learn and Be Curious

Leaders are never done learning and always seek to improve themselves. They are curious about new possibilities and act to explore them.

6) Hire and Develop the Best

Leaders raise the performance bar with every hire and promotion. They recognize exceptional talent, and willingly move them throughout the organization. Leaders develop leaders and take seriously their role in coaching others. We work on behalf of our people to invent mechanisms for development like Career Choice.

7) Insist on the Highest Standards

Leaders have relentlessly high standards — many people may think these standards are unreasonably high. Leaders are continually raising the bar and drive their teams to deliver high quality products, services, and processes. Leaders ensure that defects do not get sent down the line and that problems are fixed so they stay fixed.

8) Think Big

Thinking small is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Leaders create and communicate a bold direction that inspires results. They think differently and look around corners for ways to serve customers.

9) Bias for Action

Speed matters in business. Many decisions and actions are reversible and do not need extensive study. We value calculated risk taking.

10) Frugality

Accomplish more with less. Constraints breed resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, and invention. There are no extra points for growing headcount, budget size, or fixed expense.

11) Earn Trust

Leaders listen attentively, speak candidly, and treat others respectfully. They are vocally self-critical, even when doing so is awkward or embarrassing. Leaders do not believe their or their team’s body odor smells of perfume. They benchmark themselves and their teams against the best.

12) Dive Deep

Leaders operate at all levels, stay connected to the details, audit frequently, and are skeptical when metrics and anecdote differ. No task is beneath them.

13) Have Backbone; Disagree and Commit

Leaders are obligated to respectfully challenge decisions when they disagree, even when doing so is uncomfortable or exhausting. Leaders have conviction and are tenacious. They do not compromise for the sake of social cohesion. Once a decision is determined, they commit wholly.

14) Deliver Results

Leaders focus on the key inputs for their business and deliver them with the right quality and in a timely fashion. Despite setbacks, they rise to the occasion and never settle.

15) Strive to be Earth’s Best Employer

Leaders work every day to create a safer, more productive, higher performing, more diverse, and more just work environment. They lead with empathy, have fun at work, and make it easy for others to have fun. Leaders ask themselves: Are my fellow employees growing? Are they empowered? Are they ready for what’s next? Leaders have a vision for and commitment to their employees’ personal success, whether that be at Amazon or elsewhere.

16) Success and Scale Bring Broad Responsibility

We started in a garage, but we’re not there anymore. We are big, we impact the world, and we are far from perfect. We must be humble and thoughtful about even the secondary effects of our actions. Our local communities, planet, and future generations need us to be better every day. We must begin each day with a determination to make better, do better, and be better for our customers, our employees, our partners, and the world at large. And we must end every day knowing we can do even more tomorrow. Leaders create more than they consume and always leave things better than how they found them.

We use our Leadership Principles every day, whether we’re discussing ideas for new projects or deciding on the best way to solve a problem.

— Amazon (2025)

Amazon’s Bar Raisers

The aforementioned Leadership Principles are diligently upheld. In job interviews, this responsibility falls to a designated "Bar Raiser." Bar Raisers are Amazon employees who, in addition to their primary roles, dedicate a portion of their time to contributing to the company’s recruitment processes.

The Amazon Bar Raiser Program was established to introduce objectivity into job interviews while enhancing structure and consistency in these interactions. The initiative aims to eliminate biases within Amazon and prevent the lowering of qualification standards—a practice sometimes observed at other companies or departments when there is an urgent need for staff.

Additionally, the Bar Raiser Program seeks to preserve Amazon’s deeply ingrained culture of entrepreneurship and ownership.

The term "Bar Raiser" derives from the phrase "raise the bar," which translates to "setting a higher standard." In essence, every new employee is expected to elevate Amazon’s cultural standards by bringing their unique experiences and expertise to the table.

Amazon employees selected as Bar Raisers undergo specialized training for this role. They are granted veto power in the hiring process, enabling them to override the decisions of the hiring manager. When exercising this veto, Bar Raisers must provide a thoroughly reasoned justification, grounded in Amazon’s Leadership Principles and data gathered from the interviews.

Amazon’s Management

On July 5, 1994, Jeff Bezos founded Amazon. Exactly 27 years later, he handed over the role of CEO to Andy Jassy (see below). Since 2021, Bezos has remained involved with the company in his capacity as Executive Chair (Amazon, 2025).

See also the section Jeff Bezos & Amazon.com in Chapter 1.

Andrew R. Jassy has been with Amazon since 1997, holding various roles before contributing to the establishment of what would become AWS. From 2006 to 2016, he served as Senior Vice President, and from 2016 to 2021, he held the position of CEO of AWS. Since July 5, 2021, Jassy has been the CEO of Amazon as a whole (Amazon, 2025).

Brian Olsavsky, Amazon’s CFO since 2015, joined the company in 2002 and has held multiple finance-related positions (Amazon, 2025).

Matt Garman has been CEO of AWS since June 2024. He has been involved with AWS since 2006, playing a key role in launching the initial set of AWS services (Amazon, 2025).

Doug Herrington has served as CEO of Worldwide Amazon Stores since July 2022. Active at Amazon since 2005, Herrington has held various roles, including leading teams that developed new services such as Subscribe and Save, Amazon Fresh, Amazon Business, Alexa Shopping, and Buy with Prime (Amazon, 2025).

Additionally, Shelley Reynolds (Worldwide Controlling) and David Zapolsky (Global Affairs & Legal) are part of the group of Executive Officers (Amazon, 2025).

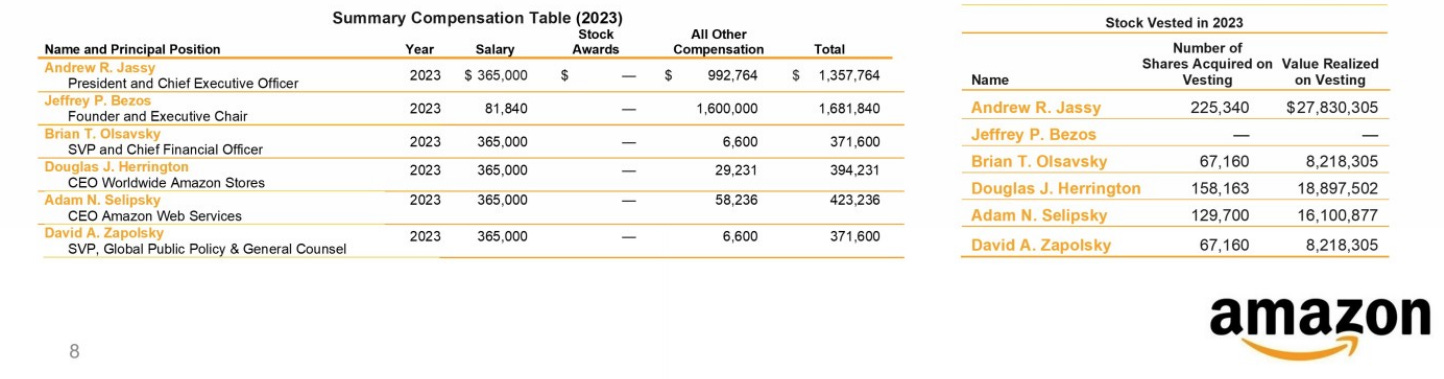

The table below provides an overview of the executive compensation for these officers.

The base salary for these directors is relatively modest, with the potential for them to supplement it through equity-based compensation. Amazon’s “compensation philosophy” is rooted in periodic awards that vest over the long term (typically with a vesting period of 5 years or more). This structure aligns the majority of executive compensation with the stock performance enjoyed by shareholders, which, over the long term, corresponds to the development of intrinsic value per share.

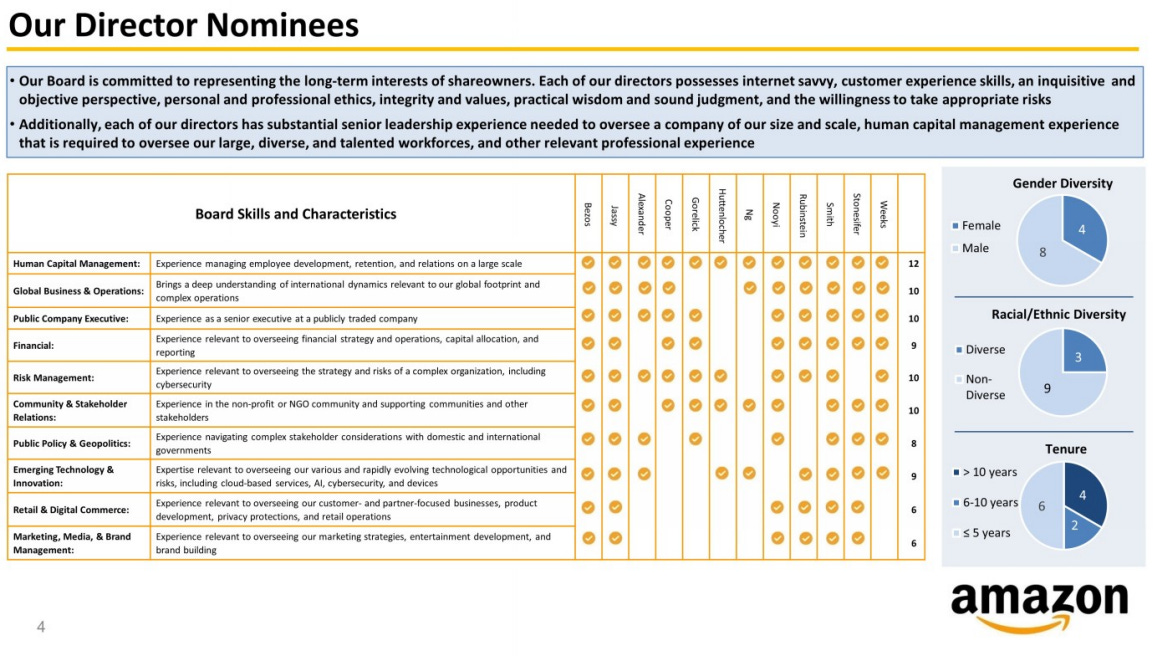

Additionally, the Board of Directors comprises various directors. In the figure below, Amazon has outlined the specific skills these directors contribute to the company.

Chapter 6 | Risks & Opportunities

Amazon outlines the risks it perceives for its various business activities in its reporting (e.g., AR2024, pp. 6-16). In this chapter, I have focused on the risks I identify for Amazon, taking into account market developments and competitor dynamics. I also highlight potential opportunities that Amazon could capitalize on.

E-commerce Customer Journey

Last year (2024), I wrote several times about the potential shifts in how consumers make online purchases. Before delving into the specific opportunities and threats for Amazon, it is useful to first consider the underlying theory.

Below, I have provided a brief overview of how consumers are currently prompted to make purchases, as well as the existing funnels that facilitate this process at present.

The process of (online) consumer purchases can be broken down into several distinct stages. Below is an overview of these stages.

1) Awareness

Before a consumer purchases a product, an initial encounter occurs. This marks the first (conscious or unconscious) contact between the consumer and a company. Following this initial interaction, an awareness process begins, during which consumers gather more information about the brand and its products, gradually forming an opinion about the company. This opinion can be positively or negatively influenced by subsequent interactions.

Various channels—or funnels—enable consumers to encounter new companies and their products or services. These include word-of-mouth recommendations, online and offline advertisements, product placements, physical locations, online platforms, entertainment, and informational content.

2) Interest/Consideration

Consumers build relationships with companies. Some relationships may never result in an economic transaction, while others may culminate in a first purchase after many years.

Strong consumer brands like Coca-Cola establish a presence in a consumer’s brand portfolio from an early age, even without direct purchases by the individual.

An extension of the awareness process and the development of a strong brand relationship is the transition to interest. At this stage, a consumer (often unconsciously) “researches” a brand and its products or services, potentially comparing it to similar competing brands where applicable. For products or services available online, this process might involve a consumer seeking additional information by subscribing to a newsletter prior to a potential first purchase or following a company’s social media accounts.

3) Desire/Intent

The third stage occurs when consumers definitively decide to purchase a product or service from a company. At this point, they draw upon their established relationship with the brand, though final considerations may still take place during the online or offline transaction.

This stage can broadly be divided into two types of consumer purchases: