Deep Dive Costco Wholesale Corporation

And the lessons we can learn from its Scale Economies Shared business model.

Costco Wholesale's strategy can be summarized as follows: offering a quality assortment of products at the lowest possible price to its members—who pay an annual membership fee—while operating cost-efficiently and aiming for high inventory turnover. The company minimizes its profit margin on merchandise to create the highest possible consumer surplus, which fosters member satisfaction and ultimately builds loyalty and trust. Since its inception, Costco has successfully compounded this approach, resulting in a loyal base of members (and fans) that continues to expand.

What lessons can we, as quality investors, learn from Costco Wholesale’s successful approach to retail?

Introduction | Costco Wholesale

Costco Wholesale Corporation (Ticker: COST 0.00%↑ , $1,071.85) is an American operator of warehouse clubs (hypermarkets), renowned for its membership-based business model: only Costco members can purchase items from the retailer's assortment of approximately <4,000 SKUs.

Founded in 1983 by Jim Sinegal and Jeffrey Brotman, Costco has grown over 40 years to nearly 900 locations worldwide across 14 countries. This expansion has propelled it to become the 20th largest publicly traded company globally by market capitalization ($475 billion as of February 17, 2025). Costco has positioned itself as the largest and most successful warehouse club in the world.

With its bulk sales, competitive pricing, and carefully curated selection of consumer products—ranging from everyday groceries and necessities to luxury items—Costco has attracted millions of members worldwide, reaching 76.2 million by the end of FY2024.

Costco distinguishes itself by passing a significant portion of its economies of scale back to its members through consistently low product prices, maintaining a markup of no more than 14% (15% for Costco's private label Kirkland Signature), with a target of 11% on Costco’s total cost of goods sold.

Maintaining these razor-thin margins is made possible by a combination of Costco’s strong customer loyalty and trust, operational efficiency, and its commitment to quality. Over the past 12 years, the company has increased its revenue from $99 billion to $254 billion, its membership base from 36.9 million to 76.2 million, and its number of warehouses from 622 to 897 (2012 and 2024, respectively).

This Deep Dive analysis will explore the key drivers behind Costco’s success—offering insights for quality-focused investors in their pursuit of the top <0.1% companies worldwide.

This Deep Dive begins at the beginning: Costco's origins and the entrepreneurial lessons from the key players who contributed to its success. It continues with Costco's strategy and business model, competitive landscape, a breakdown of the company's finances, Costco's culture and management, as well as the risks, a moat analysis, and an attempt at valuation. It concludes with a final assessment.

Below you can find the table of contents of our Deep Dive into Costco.

Chapter 1 | History

While Costco Wholesale was founded on September 15, 1983, in Seattle, Washington, the decades preceding this date saw crucial developments that would ultimately lead to Costco's creation. To accurately portray the company's history, we must look further back in time.

The genesis of Costco involves several key players who contributed to the concept as it stands today. Below are the main points from Costco's early history and background.

Sol Price & FedMart

Sol Price played a crucial role in the period preceding the initial establishment of Costco. Born in 1916 in New York to a Jewish family that had emigrated from Minsk to NYC in the early 20th century, Price and his family later relocated to San Diego, California in the late 1920s.

Price studied law and subsequently went to work as a lawyer. Shortly after the outbreak of World War II, he also worked at Consolidated Aircraft. In the post-WWII period, Price resumed his full-time career as a lawyer, eventually continuing his legal profession in a partnership formed through a merger.

At the urging of his client and close friend Mandell Weiss—co-owner of Four Star Jewelers—Price was encouraged in 1953 to visit Fedco, the rapidly growing and now largest customer of Four Star Jewelers. Fedco was a cooperative that sold household and related consumer products to U.S. government employees (including the U.S. military), operating as a non-profit for the benefit of this group and their families.

Price was enthusiastic about Fedco's business model. Consequently, Weiss and Price explored the possibilities of starting a Fedco franchise in San Diego. However, after multiple attempts and numerous concessions, this proved to be entirely unfeasible. A fortunate turn of events, as the involved parties later described, would become the catalyst for a venture that would grow faster than many dared to imagine: FedMart.

Price founded FedMart in 1954—initially involved as a co-investor and (legal) advisor—adopting the same business and membership model as Fedco: U.S. government employees could obtain a lifetime (!) membership for $2.

FedMart sold products—often on pallets—with a limited selection of product variations, in contrast to the wide variety offered by competitors. The company also stood out with its self-service store model, while many competitors at the time still operated service-based retail.

Sol Price's character and views, influenced by his background as a lawyer, were reflected in FedMart's core values. Price described FedMart's business philosophy as:

[A] professional fiduciary relationship between us and the member. You had a duty to be very, very honest and fair with them and so we avoided sales and advertising. We have in effect said that the best advertising is by our members…the unsolicited testimonial of the satisfied customer.

Unlike Fedco, FedMart was a for-profit company. While continuously striving to increase consumer surplus for the benefit of customers compared to competitors, a portion of the profits went to the FedMart Foundation, which offered scholarships to recent graduates. This foundation would eventually fund thousands of scholarships over the following 20 years.

Robert Price, Sol's son, would later join FedMart.

At its peak, FedMart would grow into a retail chain with 41 stores in the southwestern United States.

You can learn more about the life of Sol Price and the history of FedMart in Sol Price: Retail Revolutionary and Social Innovator (Robert E. Price, 2012). The FedMart years specifically are covered in The Journal of San Diego History, 56(4), 185-202 (2010).

Sol Price & Price Club

In 1976, Sol Price opened the first location of his new venture, Price Club, after gaining over 20 years of experience with his FedMart concept, where he was ousted by an investor. The inaugural store was established in an old airplane hangar on Morena Boulevard in San Diego, California. With 102,000 square feet of space, it initially offered more than 4,000 SKUs. The launch of this new concept, specifically designed for business owners, was well-advertised, as evidenced by the newspaper advertisement mentioned.

Price Club represented a significant evolution in retail, building upon Price's extensive experience and introducing a novel approach to wholesale shopping. This venture would later become a cornerstone in the development of the warehouse club model, ultimately influencing the retail landscape and leading to the creation of Costco.

You are invited to join the Price Club, a unique membership club. The Price Club offers you unusually low prices on merchandise you sell and supplies you use in your business. — Advertisement of Price Club in The San Diego Union (1976)

Memberships were available for $25 per year and were initially accessible only to business owners, positioning Price Club as a wholesaler. In the two weeks following the opening of the first warehouse, the company gained 522 members.

However, Price Club's story did not begin as successfully as FedMart's launch had. Appealing to businesses in the San Diego area proved much more challenging than targeting the consumer group Price Club initially focused on.

A few months after opening Price Club's first warehouse in San Diego, Sol Price and his team were concerned that they might not succeed in making Price Club profitable and might even have to close their business.

Sol Price and his team persevered, canvassing San Diego to sell memberships. They approached San Diego's Credit Union and managed to secure a meeting with its management.

This meeting ultimately became the catalyst for a successful partnership between Price Club and San Diego's Credit Union. The Credit Union was allowed to offer its members the opportunity to shop at Price Club under a 'group membership,' albeit with a small markup above the prices for business members.

This created a positive upward spiral for Price Club, generating more awareness among consumers and businesses.

As a result, Price Club's initial base would eventually grow to 94 branches by 1993.

Sol Price & Jim Sinegal & Jeffrey Brotman (& Costco Wholesale)

One of Sol Price's first employees, hired in 1955, was Jim Sinegal, who at 19 began working as a stocking clerk at Sol Price's very first FedMart (The Washington Post, 2009).

Jim Sinegal would later become one of the co-founders of Costco. However, this wouldn't happen until after he had spent 28 years learning every aspect of the business from his employer, Sol Price. In this process, Jim Sinegal unknowingly became the protégé of Sol Price, widely regarded as the pioneer of the warehouse business model.

In 1982, eight years into expanding his successful Price Club formula, Sol Price received a call from Bernie Brotman and his son Jeffrey Brotman, owners of a Seattle-based retailer. They inquired about the possibility of opening a Price Club franchise in Seattle.

Sol Price and his management team considered the request but ultimately declined. This was a déjà vu moment, reminiscent of when Sol Price himself was turned down in his attempt to open a Fedco franchise.

Jeffrey Brotman, much like Sol Price before him, refused to accept no for an answer. He set out to develop a plan to implement a similar business model in Seattle. For this venture, he sought someone who could assist him. Through connections, Jeffrey Brotman was led to none other than Jim Sinegal. In 1983, Jeffrey Brotman and Jim Sinegal opened their first warehouse, marking the birth of Costco Wholesale.

A few months later, Costco's first warehouse opened its doors in Seattle, Washington. With this, Costco had essentially become a clone of Price Club.

Costco would go on to generate $1 billion in revenue in less than 3 years and reach $3 billion within 6 years. (Costco, 2025). Just two years after its founding, in 1985, Costco made its IPO debut and became a publicly traded company.

Costco's rapid success was made possible in part by the fact that the company would attract many good employees from Price Club.

A Merger: PriceCostco (& back to Costco Wholesale)

Meanwhile, Price Club, located in the southern United States, experienced good years but did not achieve the same growth as Costco. The two companies crossed paths again in 1993 when they decided to merge.

In this merger, Costco shareholders received 52% of the combined company, while Price Club shareholders received 48%. It was essentially a merger of equals. PriceCostco, the name of the merged entity, had 206 locations in 1993, collectively generating $16 billion in revenue (Costco, 2025).

However, PriceCostco's existence was short-lived. In 1994, a spin-off of assets occurred, which the Price family developed into what would become PriceSmart.

The majority of Price Club remained under the Costco umbrella and would later adopt the name Costco Wholesale. In 1999, the company name was changed to its current form: Costco Wholesale Corporation.

The above paragraphs are based on Costco's own (historical) reporting and information provision, well-constructed Wikipedia pages of all aforementioned individuals and companies, and the in-depth research and detailed account of historical events by Ben Gilbert and David Rosenthal, founders of the media company and podcast show Acquired, which they conducted regarding Costco Wholesale in 2023.

For a deep dive into the complete history of Fedco, FedMart, Price Club, and Costco and their key figures, Acquired's episode on Costco Wholesale is highly recommended (Youtube, 2023).

Chapter 2 | Strategy & Business Model

Costco’s Strategy—Low prices, high quality

Costco Wholesale's strategy can be summarized as follows: offering a quality assortment of products at the lowest possible price to its members—who pay an annual membership fee—while operating cost-efficiently and aiming for high inventory turnover. The company minimizes its profit margin on merchandise to create the highest possible consumer surplus, which fosters member satisfaction and ultimately builds loyalty and trust. Since its inception, Costco has successfully compounded this approach, resulting in a loyal base of members (and fans) that continues to expand.

Costco focuses on a limited assortment of <4,000 SKUs, which is significantly low compared to other players in the retail landscape. For instance, Walmart offers more than 100,000 unique products in its hypermarkets. By concentrating on a relatively limited number of SKUs—selling only one size (ml/g), variant (flavor; packaging), or brand of a product—Costco can operate efficiently and maintain its low prices.

Our strategy is to provide our members with a broad range of high-quality merchandise at prices we believe are consistently lower than elsewhere. We seek to limit most items to fast-selling models, sizes, and colors. We carry less than 4,000 active stock keeping units (SKUs) per warehouse in our core warehouse business, significantly less than other broadline retailers. [...] Many consumable products are offered for sale in case, carton, or multiple-pack quantities only. — Costco Wholesale (2025)

Costco’s Business Model — Scale Economies Shared

Costco seeks to establish its raison d'être and commission on the added value it brings to the economy through various company-specific characteristics. These will be further explained throughout this Deep Dive, but in summary, they relate to operating in a highly cost-efficient manner while maintaining ongoing respect for its employees and suppliers.

Costco engages in fair negotiations with its suppliers, with whom it maintains good relationships—a necessity, given that Costco has significantly fewer suppliers compared to its retail competitors. This approach is sustainable due to the company's limited number of SKUs.

Costco respects its suppliers and ensures they receive fair compensation for their added value. Nevertheless, the company remains vigilant in price negotiations and continuously seeks cost advantages, viewing this as a responsibility to its members.

As Costco's warehouse base expands—reaching 897 locations as of December 31, 2024—the benefits derived from economies of scale continue to grow.

Costco prices its items with a maximum gross profit margin of 14% (15% for Costco's private label Kirkland Signature), with an overall target of 11%. For FY2024, Costco's gross profit margin was 10.92% (calculated by subtracting Merchandise Costs from Net Merchandise Sales).

This pricing strategy allows Costco to pass on over 85% (89% in FY2024) of the advantages gained from purchasing negotiations to its members. As a result, the consumer surplus continues to increase as Costco grows, creating an upward spiral of success for the company since its founding in 1983.

As Costco continues to grow, it increasingly benefits from economies of scale. This allows the company to purchase products in even larger volumes, enhancing its procurement and distribution capabilities and enabling it to negotiate lower prices. Costco passes nearly all of these advantages on to its members. This is illustrated in the figure above: for every $10 in procurement savings, Costco retains a maximum of $1.50, while at least $8.50 is returned to its members in the form of lower product prices.

This approach has enabled Costco to build its business model around the concept of Scale Economies Shared.

Scale Economies Shared

The term Scale Economies [Efficiencies] Shared—popularized by Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria of Nomad Partners—encompasses the combination of economies of scale (or efficiency scale) and the practice of sharing the resulting benefits with a company’s customers.

By passing on the advantages derived from increasing scale, a company can sustainably gain market share within an industry. This is because, with homogeneous products, consumers naturally gravitate toward the lowest price (combined with accessibility) and the best service.

This creates a flywheel effect, where new customers contribute to incrementally lower product prices, which in turn attract more customers, and so on.

“In the office we have a white board on which we have listed the (very few) investment models that work and that we can understand. Costco is the best example we can find of one of them: scale efficiencies shared. Most companies pursue scale efficiencies, but few share them. It’s the sharing that makes the model so powerful. But in the center of the model is a paradox: the company grows through giving more back.” — Nick Sleep

“We often ask companies what they would do with windfall profits, and most spend it on something or other, or return the cash to shareholders. Almost no one replies: ‘give it back to customers’ — how would that go down with Wall Street? That is why competing with Costco is so hard to do. The firm is not interested in today’s static assessment of performance. It is managing the business as if to raise the probability of long-term success. — Nick Sleep

The temptation for many companies to retain the financial benefits that arise from growth is significant. After all, there are few short-term negative consequences for businesses when they keep the advantages of growing scale for themselves.

Increasing the retail prices and justifying it on the basis that we are still “competitive” could lead to a rude awakening as it has with so many. — Sol Price

Low margins, high turnover

With razor-thin (fixed) gross margins, Costco relies heavily on the turnover rate of its inventory. An indication of how quickly this occurs at Costco can be seen in the data for Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) and [Average] Merchandise Inventories reported in the company’s filings.

Below are the figures for the most recent fiscal year, FY2024:

COGS (Merchandise Costs): $222,358 million in FY2024.

Average Merchandise Inventories (FY2024/FY2023): (($18,647 + $16,651) / 2) = $17,649 million.

Inventory Turnover: ($222,358 / $17,649) = 12.6x

This provides an indication that, with an average merchandise inventory level of just $17.7 billion, Costco was able to support $222.4 billion (!) in sales (at cost). Including Costco’s own margin, the company generated total revenue of $249.6 billion in FY2024.

For comparison, in FY2013, Costco’s average merchandise inventory was $7,495 million, which supported sales (at cost) of $91,948 million (i.e., Costco’s inventory turnover at that time was approximately 12.3x, a similar level).

In FY2024, Costco’s average inventory level was sold and replenished 12.6 times within a single year. On this, Costco achieved an approximate 11% margin, resulting in a merchandise gross profit of $27.3 billion.

Negative cash conversion cycle

On top of this, Costco also reaps the advantages of its negative cash conversion cycle. This means that Costco often sells its products before it is required to pay its suppliers. Costco’s standard payment terms are 30 days after delivery, as outlined in its standard supplier contracts:

Unless otherwise agreed in writing, Costco shall not be obligated to pay any undisputed invoice until 30 days after delivery is completed. — Costco Wholesale (2020)

Returning to the inventory turnover figure of 12.6x calculated above, this implies that, on average, a product in Costco’s inventory is sold after (365 / 12.6) = 29 days. If Costco maintained a 100% fixed assortment, the products on its shelves would, on average, be completely sold out and fully replenished 12.6 times per year.

From this, we can infer that a significant portion of Costco’s inventory is effectively financed by its suppliers. On average, Costco pays a supplier around the same time it has already sold that supplier’s products, earning an approximate gross profit margin of ~11%. We will explore this further in the finance chapter when we examine the balance sheet.

Thus, Costco’s incentive to generate higher absolute gross profits lies in increasing the transaction volume (both in size and speed) from its members. This is because the company has fixed its gross profit margin at 11% and intends to maintain it, as affirmed by management in recent earnings calls.

Driving up transaction volume—and the underlying inventory turnover speed—starts with Costco’s members. After all, only these members have access to Costco’s warehouses and merchandise. A business model based on memberships will only succeed if it is well-orchestrated.

Economies of Memberships

Membership theory teaches us that consumers will only opt for a membership when they perceive (within their own frame of reference) a greater benefit from it than the cost of the associated fees. This is often referred to as the (implied) consumer surplus. The exact magnitude of this surplus is impossible to determine objectively, as the real value of a membership is inherently subjective. It also depends on the personal frame of reference of a (potential) member and the perceived value they assign to the services and/or products offered within the membership.

Thus, it is critical for a company to: 1) effectively communicate the array of benefits a potential subscriber can gain, and 2) ensure these members are not disappointed, as they can quickly cancel their membership after a period. The latter is known as the churn rate—the percentage of the member base that cancels their subscription monthly or annually. If members do leave, they may be less likely to recommend the membership to others. In other words: 3) satisfied subscribers will, over the long term, positively contribute to acquiring new subscribers, a process strongly driven by (online) reviews and word-of-mouth marketing.

In industries where subscriptions are central, this is a key performance indicator (KPI). Consider, for example, streaming service providers like Netflix, Disney, and HBO: over the long term, a lower churn rate significantly aids in compounding intrinsic value. A lower (better) churn rate is a strong indicator of high consumer surplus and satisfaction.

That said, only companies that consistently deliver a substantial dose of (implied) consumer surplus will survive, especially in a highly competitive market with homogeneous products and/or services.

What sets Costco apart from most other companies (across various industries) with a subscription model is that Costco has not one, but two revenue streams. First, Costco collects annual membership fees ranging from $65 to $130 from its members (rates in the U.S. and Canada as of September 1, 2024). But that’s just the beginning for its members. A Costco membership on its own provides no direct value to consumers; it is merely a means to unlock value thereafter.

Once consumers commit to a membership, they aim to maximize the perceived surplus they attribute to it. With every dollar members spend at Costco’s warehouses, they redeem a small portion of this surplus. In other words, the more surplus members seek to capture, the more frequently (in terms of visits) and extensively (in terms of items in their cart) they must shop at Costco. Costco cleverly leverages this psychological dynamic.

Upon joining, the annual fee is paid upfront. This triggers an effect where members strive to extract maximum value from the prepaid subscription amount over the ensuing year. The upfront payment of this access fee amplifies this behavior. Additionally, Executive Members receive a 2% Annual Reward on up to $62,500 in purchases, which can amount to as much as $1,250 in cashback, distributed to Executive Members once annually.

Moreover, people have an inherent desire to belong to a group—a trait humanity has carried since antiquity. In ancient times, exclusion from a group drastically reduced one’s chances of survival (and even further back in history, those odds approached zero). Costco taps into this by providing for people’s basic needs (food and drink), with a focus on high quality at the lowest possible price.

Data also reveals that the average Costco member has an above-average income. In the United States, this was estimated at over $125,000 in annual income in 2023 (Numerator, 2023).

Costco reports that in FY2024, Executive Members accounted for 46.5% of its total membership base and contributed 73.3% of global Merchandise Sales. In other words, Executive Members—beyond paying a higher annual membership fee and generating greater cash flow—also drive higher merchandise profits for Costco. By the end of FY2024, Costco had 35.4 million Executive Members, reflecting a 9.6% increase from the end of FY2023.

The graph above illustrates the growth of Costco’s Executive Members (in red) and non-Executive Members (in blue), as well as the percentage of Executive Members relative to the total paid membership base (in black).

Costco also benefits from a sense of perceived exclusivity or specialty, as it offers many products in its warehouses that are unavailable elsewhere. This is because Costco negotiates unique SKUs with the majority of its suppliers, making these items slightly different (e.g., in size) from products found on competitors’ shelves.

The advantage Costco gains from this strategy is the reinforcement of its low-price perception, as many of its products are distinct or offered in larger formats. Bulk packaging inherently allows for greater cost efficiency. As a result, Costco avoids engaging in price wars with competitors selling identical products (where consumers could make direct, one-to-one comparisons).

Additionally, Costco taps into another innate human behavior: hoarding. By offering large and bulk packaging, it caters to the satisfaction members derive from purchasing in sizable quantities.

All of this is made possible because Costco has consistently built customer satisfaction, loyalty, and trust over its history. As a result, Costco members trust that the retailer secures favorable deals from suppliers and resells these products at cost plus a markup capped at 15% (~11%).

This dynamic is further supported by Costco’s relatively low number of SKUs, which makes it more challenging for suppliers to secure a spot in its assortment. In contrast to a retailer like Walmart, which offers a significantly higher number of SKUs, Costco enjoys the luxury of focusing on suppliers that deliver the best price and quality. In the fast-moving consumer goods landscape, where multiple brands (from various suppliers) compete, this works to Costco’s advantage.

Moreover, Costco’s business model—centered on offering high-quality products—provides an opportunity for premium brands like Nike and Burberry to offload excess or older inventory. Whether a would-be luxury brand like Burberry desires this association is another question, but for companies like Nike, Costco serves as an effective partner to distribute large portions of outdated stock across hundreds of locations in one fell swoop.

The combination of these elements underpins Costco’s success with its membership model.

By the end of FY2024, Costco’s renewal rate (100% minus churn rate) stood at 92.9% in the United States and Canada. In other words, out of every 1,000 members, 929 renewed their membership. Globally, this figure was 90.5% at the end of FY2024.

As of the end of FY2024, Costco had 76.2 million members worldwide, who, on average, paid approximately $63 in annual membership fees. In total, Costco generated $4.8 billion in membership fee revenue in FY2024.

Costco’s Private Label: Kirkland Signature

Costco operates its own private label, Kirkland Signature, which was introduced in 1995. The brand is named after Kirkland, Washington, where Costco’s headquarters was previously located.

Costco leverages Kirkland Signature across a wide range of product categories, including Food & Beverages (such as coffee, olive oil, eggs, and wine), Health & Wellness (vitamins, supplements, and even hearing aids), Household Goods (like detergent, toilet paper, and batteries), and even apparel.

Quality remains a key focus for Costco in this endeavor. The company collaborates with prominent brands such as Starbucks for its coffee, Duracell for its batteries, Diamond Pet Foods for its pet food, and renowned distilleries and vineyards for its wines and spirits.

We believe that Kirkland Signature products are high quality, offered at prices that are generally lower than national brands, and help lower costs, differentiate our merchandise offerings, and generally earn higher margins. We expect to continue to increase the sales penetration of our private-label items. — Costco Wholesale (AR2024)

Costco also uses Kirkland Signature as an alternative when premium brands are unwilling or unable to supply certain products at a desired price point. This can create the impression that Costco implicitly uses its private label to pressure A-brands into offering better deals. In this regard, Costco enjoys an advantageous position: if a brand refuses to negotiate, Costco can pivot to producing its own high-quality Kirkland variant and offer it to members at a lower price. However, Costco cannot over-rely on this strategy, as consumers still expect a significant presence of A-brands in its assortment.

Kirkland Signature offers significant member value compared to the national brands and continues to grow at a faster pace than our business as a whole. — Gary Millerchip, CFO (Q4 2024 Earnings Call)

When Costco can procure (or produce) its private label products at a lower cost, price reductions naturally follow due to the company’s fixed maximum gross profit margins.

Our goal is always to be the first to lower prices where we see the opportunities to do so. And just a few examples this quarter include KS [Kirkland Signature] Standard Foil reduced from $31.99 to $29.99. KS Macadamia nuts reduced from $18.99 to $13.99. KS Spanish Olive Oil 3-liter reduced from $38.99 to $34.99 and KS Baguette 2 pack reduced from $5.99 to $4.99. — Gary Millerchip, CFO (Q4 2024 Earnings Call)

Price reductions, in essence, lead to lower revenue at a constant sales volume. However, many fast-moving consumer goods (assuming sufficient local competition) exhibit relatively elastic demand specific to the company, meaning sales volumes increase when prices drop. The example below illustrates a correlation in this regard (though it does not necessarily confirm causation).

[...] Kirkland Signature Boneless Chicken Tender lines, where we lowered the price 13% and saw a 21% lift in pounds sold.

— Gary Millerchip, CFO (Q4 2024 Earnings Call)

Hot dog combo

One of Kirkland’s most iconic—if not the most iconic—products is its hot dog, sold as part of a combo with a soda for $1.50. This price has remained unchanged since 1985, despite inflation and the rising cost of production over the intervening years.

The hot dog combo has become a legendary offering for Costco.

We're known for that hot dog. That's something you don't mess with. — Jim Sinegal (CEO 1983-2011)

It’s reported that Jim Sinegal, in a conversation with his successor Craig Jelinek about a potential price increase for the combo, said, “If you raise the effing hot dog, I will kill you. Figure it out.”

As a result, this hot dog combo has become a relic for Costco—a symbol of its unwavering commitment to keeping members satisfied. In FY2023, Costco sold nearly 200 million hot dog combos.

This product, along with many others in Costco’s food courts, serves as a warm welcome to members visiting its warehouses.

Beyond this, Costco employs additional strategies to draw members to its warehouses, with its treasure hunt experience playing a significant role.

Costco? Treasure hunt!

Much like the Dutch non-food discount chain Action, Costco excels at attracting customers through its treasure hunt approach. It’s reported that approximately 25% of Costco’s assortment consists of treasure hunt items. These products are available either as one-time offerings or for a limited period each year, after which they are replaced on the shelves with new treasure hunt items, including seasonal products and luxury goods. This strategy surprises members not only with competitive pricing but also with Costco’s unique and ever-changing product selection.

One of the most exciting things about shopping in our warehouses is you never know the kind of incredible deals you’ll find from one visit to the next! Costco members know the trick to getting the best value on exclusive or one-time-buy merchandise: Visit often! And, because we rotate out and introduce new merchandise all the time, we encourage you to purchase items that interest you sooner rather than later to avoid missing out. — Costco Wholesale (2025)

This further incentivizes members to regularly visit one of Costco’s warehouses. Costco transforms these visits into an entertaining event—a fun outing—often paired with a stop at its food court.

The treasure hunt experience extends to social media, where members share their latest finds. Some members are such ardent Costco enthusiasts that they’ve created dedicated social media accounts for this purpose. For example, the account “Costcohotfinds” has posted over 3,200 updates, sharing them with its 3 million followers and turning the experience into a digital celebration.

Chapter 3 | Competition

At its core, Costco competes with the entire retail sector. After all, purchases made by customers at stores other than Costco warehouses are simply not made at Costco.

That said, there are business models within the retail industry that closely resemble Costco’s. Below, we provide more information about Sam’s Club and BJ’s Wholesale Club—two competitors that operate a similar membership-based model to Costco.

Sam’s Club (Walmart)

Sam’s Club, a division of Walmart, generated $86.2 billion in revenue in FY2024, accounting for 13% of Walmart’s total revenue. In FY2024, Sam’s Club achieved an operating profit margin of 2.5%.

Founded by Sam Walton in 1983—21 years after he established Walmart—Sam’s Club opened its first location in Oklahoma.

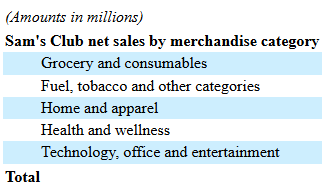

Sam’s Club operates a business model similar to Costco’s, offering an assortment of 6,000 to 7,000 SKUs across five main categories: groceries, fuel and tobacco, household and apparel, health and beauty, and technology, office, and entertainment. Below is the revenue breakdown by merchandise category for Sam’s Club over the past three fiscal years.

With 6,000 to 7,000 SKUs, Sam’s Club provides a broader product range than Costco.

In FY2024, 1.7% of Sam’s Club’s revenue came from eCommerce sales (up from 0.8% in FY2023). Sam’s Club offers two membership tiers:

Club Membership ($50/year)

Plus Membership ($110/year)

Sam’s Club operates 599 locations in the United States (down from 600 in 2022), with an average store size of 134,000 square feet. It also has international locations, primarily in Mexico and China.

Notably, Costco is mentioned exactly once in Walmart’s annual report:

Sam's Club competes with other membership-only warehouse clubs, the largest of which is Costco, as well as with discount retailers, retail and wholesale grocers, general merchandise wholesalers and distributors, gasoline stations as well as omni-channel and eCommerce retailers and catalog businesses. At Sam's Club, we provide value at members-only prices, a quality merchandise assortment, and bulk sizing to serve both our Plus and Club members. Our eCommerce website and mobile commerce applications have increasingly become important factors in our ability to compete. — Walmart (Annual Report 2024)

The data above is sourced from the websites of Walmart and Sam’s Club, as well as Walmart’s FY2024 annual report.

BJ’s Wholesale Club

BJ’s Wholesale Club (hereafter: BJ’s), also a publicly traded company (ticker: $BJ) with a market capitalization of $14 billion—significantly smaller than Costco and Walmart—recorded revenue of $19.7 billion from Q4 2023 through Q3 2024, along with $445 million in membership fee income. Like Costco, BJ’s business model is built around a membership structure.

BJ’s offers approximately 7,000 SKUs and operates in the same product categories as Costco and Sam’s Club.

With around 249 locations along the U.S. East Coast, BJ’s serves 7.5 million American members. In its FY2019 annual report, the company noted that it had 217 clubs as of February 1, 2020. Since early 2015, this number has grown by 10 clubs. Its stock price, however, has risen by 442% since February 2020.

On its trailing twelve-month (TTM) revenue of $19.7 billion, BJ’s achieved a gross profit of $3.582 million, translating to a gross profit margin of 17.8%, which includes membership fee revenue. BJ’s reported that its merchandise gross profit margin for the first nine months of 2024 did not increase compared to the same period in 2023. The company posted an operating profit of $793 million TTM, equating to an operating profit margin of 3.9%.

In its recent Q3 2024 earnings, BJ’s announced its first membership fee increase in seven years. Effective January 1, 2025, the Club Membership fee rose by $5 to $60 annually, while the Club+ Membership fee increased by $10 to $120 per year.

Sources: BJ’s Wholesale Club website, reports from 2018 through Q3 2024.

Costco’s main competitor: Consumer behavior

As previously noted in this chapter, beyond direct competitors like Sam’s Club and BJ’s Wholesale Club, which operate a similar business model, the primary driver of potential risk for Costco lies in consumer spending behavior across the broader retail landscape.

This includes not only retail chains such as Walmart, Target, Aldi, and Lidl, but also Amazon and other online players. I will elaborate on this in later chapters of this Deep Dive.

Chapter 4 | Financials

Costco’s Revenue Breakdown

As previously mentioned, Costco derives its revenue from the following two sources:

Membership Fees;

Merchandise Sales.

In FY2024, Costco generated $250 billion in revenue from Merchandise Sales and $4.8 billion from Membership Fees. This breakdown is as follows:

Approximately 98% of Costco’s revenue comes from Merchandise Sales, or store sales, while the remaining ~2% is derived from its annual Membership Fees.

From 2013 to 2024, Costco’s revenue grew at a compound annual growth rate of 8.36%. This can be broken down as follows:

Membership Fees: 7.03% CAGR;

Merchandise Sales: 8.39% CAGR.

Below is a schematic representation of the development of Costco’s revenue sources since FY2013.

As you can see, the growth in Costco’s revenue began to accelerate after 2017, with an additional surge during the COVID-19 years of 2021 and 2022. Over the past two years, this growth has somewhat normalized.

In the graph above—which displays year-over-year (YoY) revenue growth—this normalization is also evident: FY2024 marked a year of stabilization in Costco’s revenue growth, with YoY increases of 5.41% for Membership Fees and 5.01% for Merchandise Sales.

Revenue by Geography

In FY2024, Costco relied on the United States for approximately 72% of its sales. When combined with revenue from Canada (approximately 14%), this accounts for roughly 86% of its total revenue. All other countries collectively contribute about 14%.

In the U.S. and Canada, approximately 81% of Costco’s warehouses are located. The Asia-Pacific region currently contributes 8.5% to the total number of warehouses (76 out of 897), up from 7.0% in 2017.

Merchandise Sales per Member

As previously established, Costco cannot increase its absolute profits by raising margins on its merchandise—the company aims to keep these below 14-15% for individual products, targeting a weighted average of 11%.

However, Costco can boost absolute profits from merchandise by increasing sales volume. When members spend an additional $X annually in Costco’s warehouses, approximately 11% of that flows into Costco’s absolute gross profit.

Thus, as Costco’s members spend more per person—combined with the addition of new members each year—the absolute profits from merchandise sales also grow incrementally.

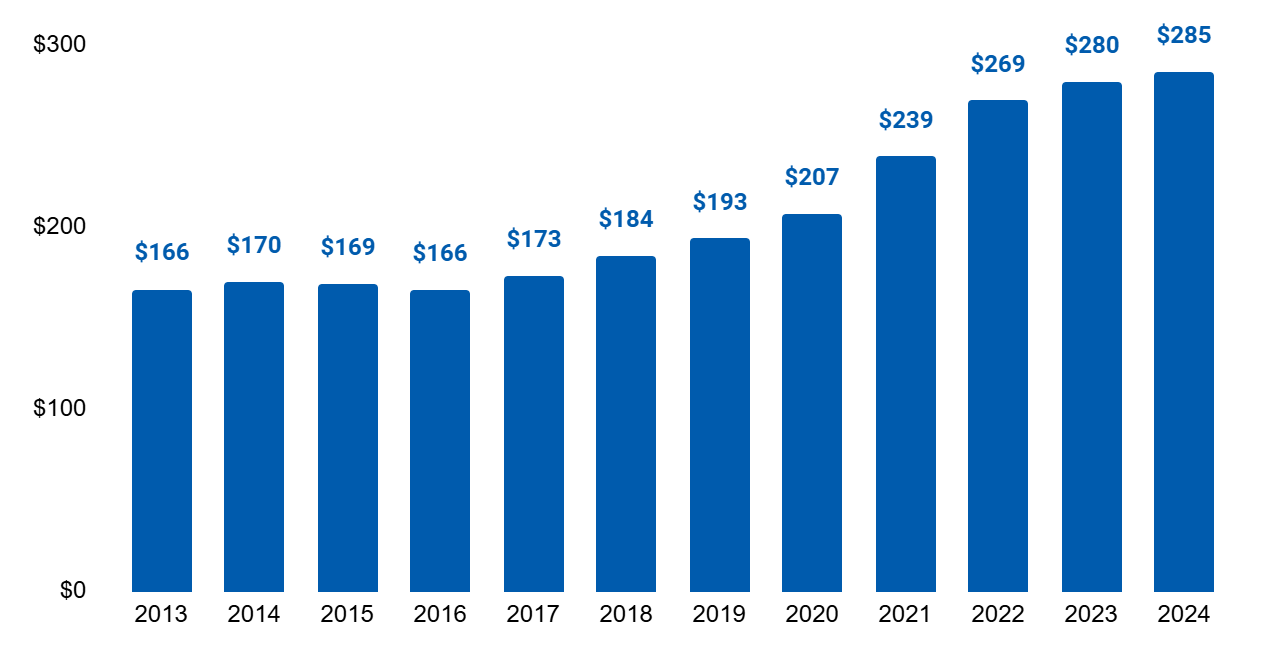

Below is a graph illustrating the development of Merchandise Sales spending per member (calculated based on the average number of members in a given year).

This metric has declined over the past two years because Costco’s number of Paid Members grew more rapidly (+7.3% | +7.9%) than its total Merchandise Sales (+5.0% | 6.7%) in FY24/FY23 and FY23/FY22, respectively. As a result, the average Merchandise Sales per member has decreased over Costco’s last two fiscal years.

>>> Overall, Costco’s number of Paid Members increased at a compound annual growth rate of 6.28% since 2013, rising from 39 million in FY2013 to 76.2 million in FY2024.

>>> The average Merchandise Sales per member grew at a CAGR of 2.06%, from $2,711 in FY2013 to $3,392 in FY2024.

Together, these factors contribute to the total Merchandise Sales CAGR of 8.39%.

Gross Profit (Margin)

As previously noted, Costco prices its products with a maximum gross profit margin of 14% (15% for Kirkland Signature products), targeting an overall average of 11%.

When Merchandise Costs are subtracted from Merchandise Sales, the result is the Merchandise Gross Profit. The trend of this metric since 2013 is illustrated in the graph below (expressed as a percentage of Merchandise Sales).

Costco has been quite successful in maintaining a gross profit margin of around 11% on its total Merchandise Sales: over the past 11 years, the average gross profit margin was 10.95%. In FY2024, Costco’s gross profit margin stood at 10.92%.

Since 2013, Costco’s gross profit has grown at a CAGR of 8.67%, roughly in line with the growth rate of its Merchandise Sales. If Costco maintains its gross profit margin target, future increases in its absolute gross profit will be driven by revenue growth.

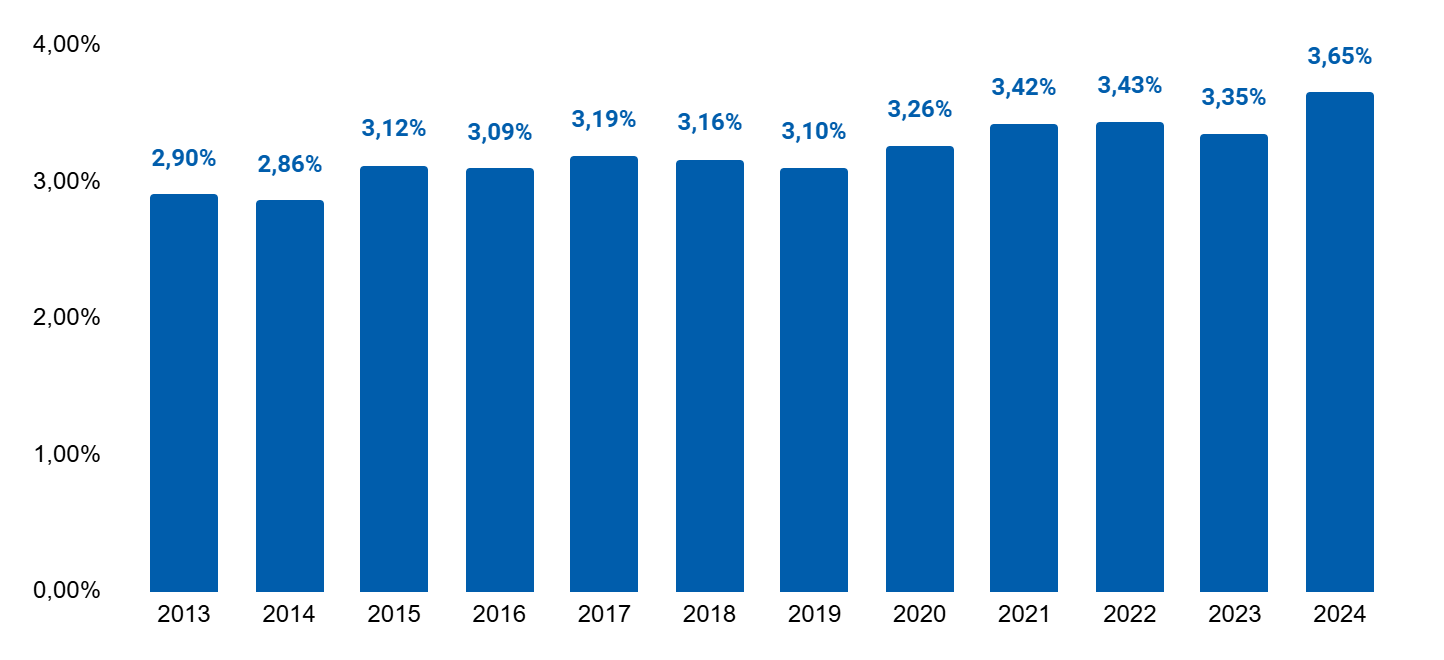

Operating Income

From 2013 to 2024, Costco’s operating income grew at a compound annual growth rate of 10.64%. This exceeds the CAGR of Costco’s revenue (8.36%) and gross profit (8.67%) increases. The primary reason for this is lower incremental overhead costs. These costs are not included in the cost of goods sold (used to calculate gross profit), allowing Costco to retain these cost savings (or benefits derived from overhead costs rising more slowly than revenue growth). This figure also incorporates the increased revenue from Costco’s Membership Fees.

The graph above displays Costco’s operating profit margin (Operating Income / Total Revenue). This margin rose from 2.90% in FY2013 to 3.65% in FY2024.

Net Income

Costco’s net income grew at a CAGR of 12.39% since 2013, with its net profit margin increasing from 1.94% in FY2013 to 2.90% in FY2024. The trend of this net profit margin is illustrated in the graph below.

In addition to Costco’s operational economies of scale, an interest component also contributes to its Net Profit CAGR. In FY2013, Costco recorded net interest expenses (interest income minus interest expenses) of $2 million. By FY2024, this had shifted to a positive surplus of $455 million.

Shares Outstanding & EPS Development

The number of Costco’s outstanding shares has remained relatively stable over the past 11 years. In FY2013, Costco had 440.5 million shares outstanding, which increased to 444.8 million in FY2024. This reflects a CAGR of 0.09%, rendering its impact on the difference between Costco’s Net Income and Earnings Per Share (EPS) negligible.

Consequently, Costco’s EPS growth, at a CAGR of 12.28%, closely aligns with its net income growth of 12.39% CAGR.

The graph below illustrates the trend of Costco’s diluted EPS over the period from FY2013 to FY2024.

Below is a graph showing the year-over-year change in Costco’s diluted EPS.

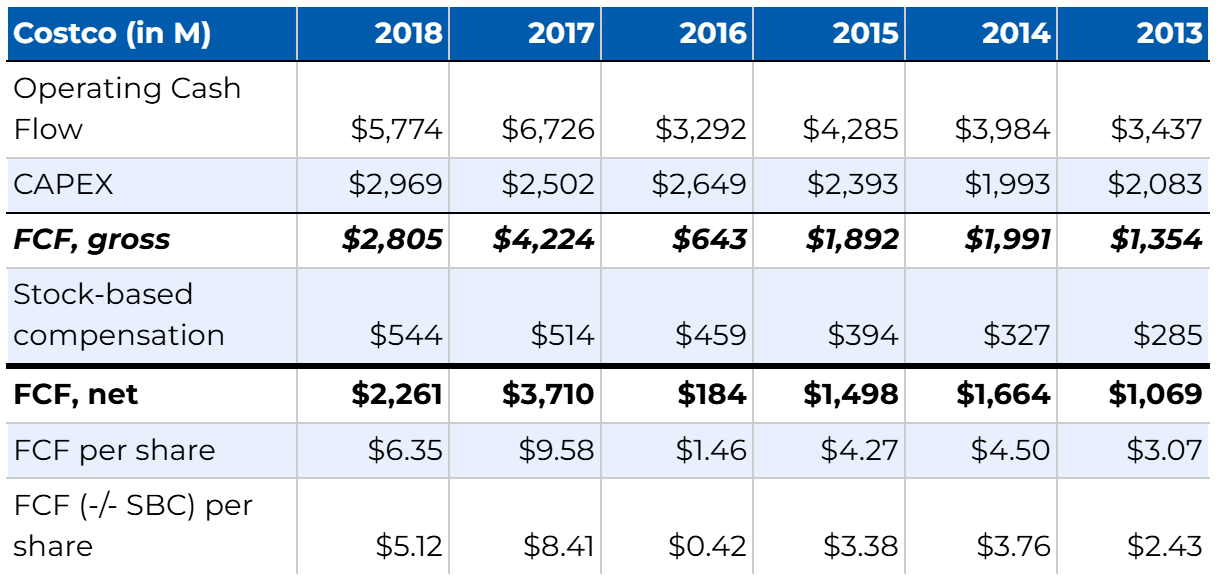

Costco’s Cash Flows — OCF, FCF & SBC

Costco’s cash flow from operating activities increased from $3,437 million in FY2013 to $11,339 million in FY2024, representing a compound annual growth rate of 11.46%.

Meanwhile, Costco’s capital expenditures (CAPEX) grew at a CAGR of 7.70%, rising from $2,083 million in FY2013 to $4,710 million in FY2024.

Due to these CAPEX investments growing at a slower rate than operating cash flow, Costco’s (gross) free cash flow (FCF) increased from $1,354 million in FY2013 to $6,629 million in FY2024—a CAGR of 15.53%.

Costco’s stock-based compensation (SBC) rose from $285 million in FY2013 to $818 million in FY2024, reflecting a CAGR of 10.06%.

Because Costco’s SBC grew more slowly than its gross FCF in recent years, the company’s net FCF increased at an even faster pace: with a CAGR of 16.64%, net FCF climbed from $1,069 million in FY2013 to $5,811 million in FY2024. Over this period, Costco’s market capitalization grew at a CAGR of 20.70%.

Costco’s FCF (OCF -/- CAPEX) per share increased at a CAGR of 15.43%, rising from $3.07 per share in FY2013 to $14.90 per share in FY2024. The trend of Costco’s FCF per share over the years is illustrated below.

Costco’s Balance Sheet

As of September 1, 2024, Costco Wholesale reported total assets of $69.8 billion. This is balanced by $46.2 billion in liabilities and $23.6 billion in equity.

Of Costco’s $69.8 billion in assets, $29 billion is attributed to Property & Equipment. In its FY2024 annual report, Costco disclosed that out of its 890 warehouses, 703 are fully owned by the company (including both land and buildings). For 134 warehouses, the land is leased while the buildings are owned by Costco, and for the remaining 53 warehouses, both the land and buildings are leased.

The balance sheet below highlights Costco’s current assets and short-term liabilities. Costco’s Cash & Cash Equivalents (C&CE), totaling $9.9 billion, and its Merchandise Inventories, valued at $18.6 billion, constitute a significant portion of its current assets.

As evident in the short-term liabilities section, the amount of Costco’s Merchandise Inventories closely aligns with its Accounts Payable. This balance sheet item totals $19.4 billion, roughly equivalent to Costco’s inventory value.

This demonstrates that Costco finances its inventory levels through its trade creditors, as previously explained.

Ultimately, this inventory level—averaging approximately $18 billion—supports Costco’s revenue, which amounted to $249.6 billion in Merchandise Sales in FY2024.

As of now, Costco boasts a market capitalization of $475 billion. This represents a multiple of 6.7 times the company’s total assets.

Displayed below are Costco’s financial KPIs over the past 11 years.

Data Costco Wholesale — Profit & Loss Statement

Data Costco Wholesale — Cash Flow Statement

Data Costco Wholesale — Ratios

Sources: Costco Annual Reports 2013-2024.

Chapter 5 | Culture & Management

Customer Satisfaction

At Costco, the customer—alongside compliance with the law, care for employees, and respect for suppliers—takes center stage, as outlined in the company’s Code of Ethics, which is published on its website (Costco, 2025):

Obey the law

Take care of our members

Take care of our employees

Respect our suppliers

Risk-Free 100% Satisfaction Guarantee

Costco demonstrates this commitment through its exceptionally generous return policy, allowing nearly all products to be returned at any time.

Additionally, the company refunds the difference if a product purchased goes on sale within the following 30 calendar days. Costco also provides an extra two years of warranty beyond the manufacturer’s warranty on products such as televisions, projectors, computers, and various major appliances.

Moreover, Costco strives to assist its members directly with solutions to issues, without redirecting them to other locations or deferring assistance to a later time.

Members also have the option to cancel their membership immediately if they are dissatisfied. If a member does not use their membership for an entire year, Costco refunds the upfront membership fee paid.

Naturally, Costco prefers to see all its members actively shopping, but even with the small group of members who ultimately make no purchases during their membership year, the company still benefits. This is because Costco receives the membership fee as FCF at the start of the membership year, positively impacting its working capital. This cash can then be allocated to inventory or short-term bonds, generating merchandise or interest returns.

Source: Costco Customer Service.

Employee Satisfaction

In FY2024, Costco achieved a retention rate of 93% among its employees (for those employed with Costco for over one year in the U.S. and Canada). This figure was 90% in both FY2023 and FY2022, significantly exceeding the industry average. Costco aims to maintain at least 50% of its workforce as full-time employees.

On Glassdoor (2025), Costco Wholesale earned an overall rating of 3.9 out of 5.0 based on 18,885 reviews, with 74% of reviewers indicating they would recommend working at Costco to a friend. In comparison, Walmart scored 3.4 out of 5.0 (140,160 reviews) with a 55% recommendation rate; Sam’s Club scored 3.3 out of 5.0 (13,253 reviews) with 52%; and BJ’s Wholesale Club scored 3.0 out of 5.0 (3,690 reviews) with 40%.

Thus, Costco receives both a higher overall rating and a higher recommendation percentage from its employees compared to its U.S. competitors.

Costco is widely recognized as an exemplary employer in the retail sector, particularly in terms of compensation and healthcare benefits.

Costco strives to provide our employees with competitive wages and excellent benefits. In July 2024, we increased the starting wage to at least $19.50 for all entry-level positions in the U.S. and Canada. We also increased the top of wage scales by $1 per hour, and increased all other steps of the wage scales by $0.50 per hour, bringing our average hourly rate at the end of 2024 for hourly employees in the U.S. to approximately $31 per hour. — Costco Wholesale (Annual Report FY2024)

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025), the average hourly wage in the retail trade sector was $24.98 in January 2025. Costco’s average hourly wage exceeds this industry average by more than 24%.

As a management team, we continue to be incredibly proud of our 333,000 employees worldwide and the culture that they foster. The consistency of our financial results is a reflection of the commitment of our entire team to member service and the Costco experience. Most of these employees are led by our fantastic warehouse managers, who we view as executives in our company. Succession planning continues to be a key focal point for us, as we're continually working on identifying the future leaders of our company. In FY2024, we promoted 95 new warehouse managers. 85% of those promoted, started at Costco as an hourly employee. This promotes from within the culture, and the long-term career it helps to build, is core to who we are as a company, community member, and retailer. — Ron Vachris (Q4 2024 Earnings Call)

In FY2024, 85% of promoted warehouse managers at Costco began their careers in entry-level, floor-level positions. This is a remarkable statistic, as it not only reflects the years of experience these employees bring from their prior roles but also highlights a company culture that rewards strong performance. Furthermore, it underscores the employee satisfaction of these individuals, as they choose to remain with Costco for an extended period.

A similar trend is evident among Costco’s executive-level management.

Costco’s Management

Since its founding in 1983, Costco has had only three CEOs (two of whom served over a 40-year span):

Jim Sinegal (1983-2011)

Craig Jelinek (2012-2023)

Ron Vachris (2024-present)

Both Jim Sinegal and Craig Jelinek remained with Costco as advisors following their tenures as CEO.

Ron Vachris, who became CEO on January 1, 2024, started his career at age 18 in 1982 with Price Club as a forklift driver. Over the ensuing years, he steadily advanced, taking on various roles, including assistant manager and manager of individual warehouses.

From 2010, Vachris served as Senior Vice President and General Manager of the Northwest Region. He then held the position of Executive Vice President of Merchandising from 2016 to 2022, before assuming the role of Chief Operating Officer (COO) in the two years leading up to his appointment as CEO.

Sources: Costco Wholesale, Crunchbase.

Ron Vachris’s base salary is $1.08 million. In addition, he received stock awards valued at $10.6 million over the past year. Combined with other miscellaneous compensation, his total remuneration in FY2024 amounted to $12.2 million. The stock awards cannot be sold immediately; they are subject to a vesting period of 3–5 years, with portions released annually for potential sale.

Our compensation programs are designed to motivate our executives and employees and enable them to participate in the growth of our business. The Company believes it has been very successful in attracting and retaining quality employees, generally achieving low turnover in our executive, staff and warehouse management ranks. In addition, in the judgment of the Compensation Committee, the programs have contributed to the financial and competitive success of the Company. Accordingly, the Committee believes it is desirable to continue these programs. — Costco Wholesale (2024)

This structure incentivizes executives and managers to focus on long-term performance, as the majority of their share-based compensation—which constitutes the bulk of their total compensation—depends on the long-term progression of the company, reflected in its stock price. Over the long term, this is underpinned by the development of intrinsic value per share.

Costco’s CFO, Gary Millerchip, succeeded Richard Galanti (CFO since 1985) in March 2024, marking the first transition in the financial leadership role in 39 years. Prior to joining Costco, Millerchip served as CFO of Kroger starting in 2019, where he worked for a total of 15 years. Before that, he held positions in the banking sector.

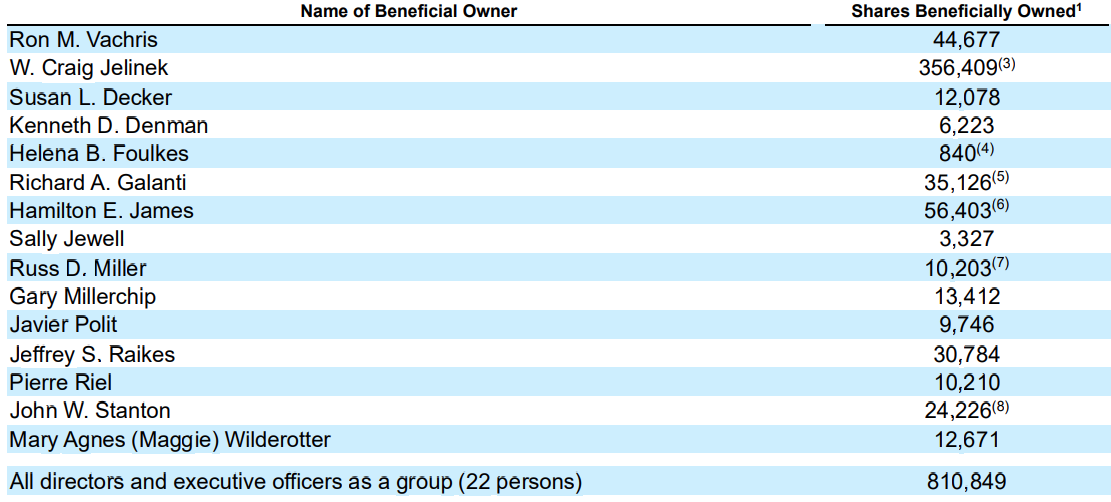

Skin in the game

The table below details the shareholdings of Costco’s board of directors. As shown, Mr. Jelinek, who served as CEO from 2012 to 2023, has built and maintained a substantial position in $COST over the years, allowing him to continue reaping the rewards of his past efforts.

I consider Costco’s stock-based compensation to be appropriate in both its nature and scale. In FY2024, SBC amounted to $818 million, representing 12.3% of the company’s gross FCF of $6,629 million and 0.3% of its revenue of $254,453 million.

A Tribute to Charlie Munger

Charlie Munger (1924–2023) played a pivotal role in furthering the success of Costco Wholesale. He joined the company’s board of directors in 1997, serving in a non-executive, advisory capacity for 24 years until 2021.

Initially, Warren Buffett was approached to fill a board seat, but after declining, he referred Costco to Charlie Munger.

Munger frequently expressed his admiration for Costco. Below are a few quotes in his memory and as a tribute to his dedication to the company:

I love everything about Costco. I'm a total addict, and I'm never going to sell a share.

I admired the place so much that I violated my rules [against sitting on outside boards]. It's hard to think of people who've done more in my lifetime to change the world of retailing for good, for added human happiness to the customer.

I’m no good at exits. I don’t like even looking for exits. I’m looking for holds. Think of the pleasure I’ve got from watching Costco march ahead. Such an utter meritocracy and it does so well, why would I trade that experience for a series of transactions? I’d be less rich not more after taxes. The second place is a much less satisfactory life than rooting for people I like and admire. So I say find Costco’s, not good exits.

Nothing to add, Charlie.

Ultimately, in my view, investing is about putting capital into companies that add value to society and then holding onto them for as long as possible. It’s about joining the company and its stakeholders on their compounding journey—a pursuit that brings a sense of fulfillment and joy.

Chapter 6 | Risks

The transition from the previous paragraph is abrupt, but it’s worth noting that Costco, too, faces risks that we must examine to arrive at a well-balanced final assessment.

Costco is a company reliant on the future spending behavior of consumers. Shifts in this behavior toward other players could harm Costco, even if these shifts occur at an almost imperceptible pace.

Such developments would become apparent if Costco consistently reports growth figures lower than those of its direct competitors and the broader retail sector, which would suggest a loss of market share.

The retail business is highly competitive. We compete for members, employees, sites, products and services and in other important respects with a wide range of local, regional and national wholesalers and retailers, both in the United States and in foreign countries, including other warehouse-club operators, supermarkets, supercenters, online retailers, gasoline stations, hard discounters, department and specialty stores and operators selling a single category or narrow range of merchandise. — Costco Wholesale (2024)

One risk, which I consider highly unlikely but potentially devastating in impact, lies in the loss of its goodwill, customer satisfaction, and loyalty. These elements currently represent a significant strength for Costco, built over a long period. Losing them could prove catastrophic, as Costco’s business model is fundamentally rooted in these attributes.

I also see risks related to the company’s IT strategy. If artificial intelligence (AI) fulfills its promises, and competing retailers have already integrated AI applications into their business processes—passing the resulting benefits on to their members—while Costco fails to do so, I believe there’s a substantial chance that some of Costco’s members could shift to lower-cost alternatives. Costco acknowledges these risks itself:

The evolution of retailing in online and mobile channels has improved the ability of customers to comparison shop, which has enhanced competition. Some competitors have greater financial resources and technology capabilities, including the faster adoption of artificial intelligence, better access to merchandise, and greater market penetration than we do. Our inability to respond effectively to competitive pressures, changes in the retail markets or customer expectations could result in lost market share and negatively affect our financial results. — Costco Wholesale (2024)

For instance, Costco competes with Amazon across numerous product categories. If Amazon successfully further adopts AI in its distribution processes, reducing its cost base and passing those savings on to customers, this poses a risk to Costco. In such a scenario, Costco might need to raise its product prices more quickly or reduce them more slowly in the future due to the absence of similar cost savings.

Additionally, Costco highlights in its annual report its heavy revenue concentration in the United States and Canada—which together account for 86% of net sales and 85% of operating income—as well as risks related to distribution issues and supplier dependency. I view these as minimal risks over the long term, given the progress of the U.S. and Canada as Western nations, their economic development, and future outlook.

The company also mentions generic risks such as developments in the (international) economy, climate, and legal and regulatory changes.

Furthermore, should consumer eating habits undergo a lasting shift, I expect Costco’s management to respond promptly. By keeping its members at the forefront, I consider it highly likely that the company will navigate such changes successfully.

Chapter 7 | Moat Analysis

What sets Costco apart from its competitors? What constitutes Costco’s Moat?

Throughout my research, as I’ve aimed to illustrate properly in this deep dive, Costco stands out for its exceptional customer and employee satisfaction and loyalty. The foundations of this lie in Costco’s high-quality customer service, driven by its 330,000 employees worldwide (with a 93% retention rate in the U.S. and Canada for employees with 1+ years of service)—whom Costco strives to compensate fairly for their efforts—as well as the company’s daily commitment to improving efficiency, cutting costs, and securing procurement advantages, the vast majority of which are passed on to its members. These members, in turn, exhibit a retention rate of 92.9% in the U.S. and Canada and 90.5% globally.

This fosters a significant goodwill factor, with members trusting Costco’s pricing due to its long-established track record. Deviating from its stated gross profit margin targets, compromising its high-quality customer service, or altering other defining aspects that have shaped and strengthened Costco over decades could severely undermine consumer trust. Yet, this also underscores Costco’s strength.

Costco’s balance sheet totals approximately $70 billion. If you were to give a group of astute entrepreneurs the same $70 billion, I believe they would face considerable difficulty replicating Costco. Brand recognition, goodwill, and loyalty cannot be directly (and profitably) reproduced with money alone. Time is a critical variable in this equation.

Although switching costs for consumers would not be high in the case of an exact Costco replica (a membership can be canceled easily), Costco’s intellectual property (IP) is robust, rooted in the factors mentioned above. This makes it challenging for a new competitor to fully replicate Costco in existing markets.

To succeed, a competitor would need to offer not just a marginal increase in consumer surplus but a substantially greater one. This is not feasible profitably on a small scale, as Costco’s business model already passes on significant benefits and operates with razor-thin merchandise margins enabled by its existing scale.

This positions Costco’s large size as a barrier to competition. While direct competition is not entirely precluded, it is significantly hindered. Although Costco, aside from its Kirkland Signature brand, is not a proprietary brand, it still derives advantages from its IP. Rather than using this for pricing power, Costco leverages it to continually enhance consumer surplus for its members, amplifying additional economies of scale: Scale Economies Shared.

Because consumers trust Costco’s underlying pricing variables, the company does possess pricing power in the sense that it can pass on future increases in procurement costs—inevitable with inflation—directly to its customers on a one-to-one basis. In the end, it is about maintaining consumer surplus relative to competitors.

As an investor, you seek to invest in companies that, beyond benefiting from revenue growth driven by secular trends, are inflation-proof and can sustain profit margins through a well-established moat.

Costco embodies all these qualities: revenue growth from expansion (more on this in the next chapter), a moat derived from economies of scale, and resilience against inflation.

The latter is evident in the fact that for every $10 in increased procurement costs, Costco passes on approximately $11.10 to its members in the form of higher prices (an ~11% markup), adding ~$1.10 to its own gross profit. This Scale Economies Shared dynamic thus also works in reverse, benefiting Costco during periods of product inflation and therefore making it an inflation proof company.

In summary, I would certainly consider including Costco in my portfolio when the price is right. Whether that is the case will be explored in the next chapter: Valuation.

Chapter 8 | Valuation

Is Costco currently attractively valued?

To address the question above, it’s helpful to first dissect Costco’s historical performance.

Since the end of FY2013, the number of Costco warehouses has grown at a CAGR of 3.15%. This reflects the growth from Costco’s physical expansion. Additionally, there is growth derived from Like-for-Like (LFL) sales increases. We can approximate this by examining Costco’s average revenue per warehouse.

The table above lists the average annual Merchandise Sales per cohort of Costco warehouses. As shown, these figures rise over time, with new locations also generating higher revenue in their first year (a trend partly driven by inflation).

I calculate Costco’s total LFL growth progression by dividing the total Merchandise Sales in a fiscal year by the average number of warehouses in that year. This yields the trend outlined below.

This metric increased from an average of $166 million in revenue per warehouse in FY2013 to $285 million per warehouse in FY2024, representing a CAGR of 5.05%.

Combined with the expansion growth of 3.15% CAGR, this constitutes the total growth rate of Costco’s Merchandise Sales (8.39%).

The graph below illustrates the year-over-year growth in LFL sales (blue) and expansion (red), as calculated using the methodology described above.

As you can observe, Costco’s Like-for-Like (LFL) growth has moderated following two exceptionally strong pandemic years (2021 and 2022), which were partly fueled by inflation. This results in a growth rate for Costco’s LFL growth of 5.05% CAGR since FY2013. For my valuation analysis, I round this figure to 5%.

Additionally, the company pursues a carefully planned expansion growth of 2–4% annually, yielding a CAGR of 3.15% for expansion since FY2013.

For FY2025, Costco has scheduled the addition of 26 new (net) warehouses, with 12 located outside the United States. Adding 26 to the existing 890 warehouses (as of the end of FY2024) implies an expansion growth rate of 2.92% year-over-year (YoY) in FY2025. For my valuation analysis, I assume a future expansion CAGR of 2.5%, reflecting confidence in Costco’s continued successful expansion beyond the U.S.

Together, this results in a projected CAGR of 7.5% for Costco’s future Merchandise Sales growth.

Costco’s Membership Fees have grown at a CAGR of 7.03% since 2013. This includes a fee increase introduced at the end of FY2024, the full impact of which will gradually reflect in Costco’s financials over time.

For Membership Fees growth, I also adopt a 7.5% CAGR, implying an overall revenue growth rate of 7.5% CAGR for Costco.

Consequently, Costco’s revenue—and its gross profit, assuming it maintains its ~11% gross profit margin—will grow at a CAGR of 7.5%.

For FY2025, Costco anticipates capital expenditures of approximately $5 billion, a 6.2% increase from FY2024. Over the past 11 years, Costco’s CAPEX has risen at a CAGR of 7.7%, a rate mirrored by its selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses.

Costco’s financials reveal faster growth in operating income, net income, and free cash flows over the past decade, with CAGRs of 8.67%, 12.39%, and 15.53%, respectively, since FY2013.

For the future, however, I will use more conservative growth rates for these metrics, as Costco has already reaped significant benefits from its increased scale.

I believe Costco can achieve a FCF growth rate of 10% CAGR in the coming years. This is lower than the 15.53% CAGR recorded from FY2013 to FY2024 but, in my view, aligns with the company’s current size.

Currently, Costco trades at 72x its FY2024 FCF (82x when adjusted for stock-based compensation). According to FinanceCharts data, Costco’s current price-to-free-cash-flow (P/FCF) ratio appears notably high compared to historical valuations.

This is reflected in its stock performance as well. Over the past 12 months, Costco shareholders enjoyed a 46.1% shareholder return (excluding dividends), while its YoY FCF declined by 1.7%. This positions Costco at a very elevated P/FCF level, as also depicted in the FinanceCharts graph below.

Historically, peaks in Costco’s P/FCF ratio have moderated due to stabilization driven by higher FCF.

Now, we reach the point where we must assign a multiple to Costco’s fundamentals to arrive at a valuation. For a company as robust as Costco—with its moat and an implied FCF growth rate of 10% CAGR, with potential upside from further successful international expansion—I believe a multiple of 25x its SBC-adjusted cash flow from operating activities (OCF) is well justifiable. This translates to a multiple of approximately 39.7x Costco’s FCF (which, based on the graph above, aligns roughly with its historical average). This would imply an FCF yield of 2.52%, increasing annually by 10% relative to the buy-in level (e.g., n+1 = 2.77%, n+2 = 3.05%, etc.).

Applying this to an OCF minus SBC of $10.5 billion in FY2024 results in an implied market capitalization of approximately $263 billion—significantly below Costco’s current valuation of $475 billion.

Expressed per share, this yields a target price (TP), excluding any safety margins, of $591 per share. For context, this was Costco’s stock price at the end of 2023. Since then, the company’s market capitalization has surged by 77%, despite what I see as a lack of commensurate growth in intrinsic value (revenue increased by 5% and operating income by 14.4% since then).

Chapter 9 | Conclusion

I find Costco’s current valuation too steep to justify an investment at this time. At a price below $600 per share, an investor could expect an internal rate of return (IRR) of approximately 10%, assuming Costco’s implied multiples hold steady in the future. However, if these multiples were to experience shrinkage, that return would decrease by a few percentage points.

My required return for portfolio companies is 10%. Consequently, I will not be adding Costco to my portfolio at this stage. That said, it will remain on my watchlist. Should its stock price decline or its fundamentals exceed expectations (and sustain that performance), Costco could potentially join my portfolio at a later date.

Nevertheless, in my view, it remains one of the world’s strongest companies, exhibiting the various qualities I’ve detailed in this deep dive.

May we, as quality-focused investors, and as fellow human beings, learn from this wonderful company,

Eelze Pieters

February 17, 2025

Costco is a business that became the best in the world in its category. And it did it with an extreme meritocracy. And an extreme ethical duty. — Charlie Munger

Colophon

Published by

Massive Moats

Author

Eelze Pieters

Social Media

@massivemoats

Contact

T +31 (0)620278347

info@massivemoats.com

https://massivemoats.com

February, 2025

© 2025 Massive Moats

Disclaimer

The information above is provided for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, accounting and/or financial advice. You should consult directly with a professional if financial, accounting, tax or other expertise is required.