A Deep Dive Analysis into the Nomad Investment Partnership

Exploring the Wisdom of Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria in Long-Term Value Creation

Executive Summary

This article explores the investment philosophy and evolution of Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria, the founders of Nomad Investment Partnership, highlighting key principles that drove their exceptional returns from 2001 to 2013. Initially rooted in a rigorous contrarian value approach, Nomad sought companies trading at significant discounts to their intrinsic value, often in overlooked or distressed markets. However, their journey quickly evolved beyond traditional value investing.

A pivotal shift occurred with the recognition of "super high-quality thinkers"—businesses characterized by deep, enduring competitive advantages (moats), discipline in capital allocation, and the strategic sharing of scale economies with customers. This "Scale Economies Shared" model, exemplified by their cornerstone investment in Costco Wholesale, became a hallmark of their strategy, prioritizing long-term customer benefit over short-term profitability. This deep understanding of customer-centricity and the underlying culture that fosters it proved critical to identifying compounding machines.

Nomad's approach to portfolio management also evolved, moving from a broadly diversified portfolio to one of high conviction and concentration, particularly in companies like Amazon, where the long-term destination of the business far outweighed valuation considerations. Critically, Sleep and Zakaria emphasized the paramount importance of a long-term mindset, urging investors to disregard short-term market noise and benchmark distractions. They viewed volatility not as risk, but as an opportunity, and candidly discussed their own errors of omission, particularly selling compounders too early, which profoundly shaped their subsequent investment decisions.

Ultimately, Sleep and Zakaria concluded Nomad to pursue philanthropic endeavors. Their legacy offers invaluable lessons on patience, psychological discipline, and the profound power of investing in exceptional businesses with durable moats and a commitment to customer value.

I wish you an insightful journey through the full story of the Nomad Investment Partnership.

Chapter 1 | The Genesis

There are, perhaps, few things finer than the pleasure of finding out something new. Discovery is one of the joys of life and, in our opinion, is one of the real thrills of the investment process.

— Nick Sleep

The Encounter

Nicholas David Mark Sleep (United Kingdom, 1968) and Qais "Zak" Zakaria (Iraq, 1969) first met in the late 20th century, both independently seeking investment opportunities within the Asian markets. At the time, Sleep worked at Marathon Asset Management in London, having joined in 1995 after serving as an investment analyst at Sun Life of Canada. Zakaria, a sell-side analyst at Deutsche Bank specializing in Asian equities, encountered Sleep when both were in their late twenties. Amidst the post-dot-com bubble market chaos, Zakaria departed Deutsche Bank to join Marathon Asset Management—a decision that laid the foundation for their eventual launch of the Nomad Investment Partnership.

Warren Buffett's Influence

In May 2000, Sleep and Zakaria's joint trip to Omaha for Berkshire Hathaway's annual shareholder meeting proved pivotal. This experience inspired Sleep's subsequent plans, quickly embraced by Zakaria, to establish their own fund. Their objective was to build upon Warren Buffett's core investment principles, consciously distinguishing themselves from what they termed "the sin and folly" and the "short-term crowd" pervasive in the financial sector.

Guiding Principles

Driven by an unwavering moral standard and a commitment to quality of life—inspired by the ethos in Robert Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974)—their mission was unequivocally clear: to execute their fiduciary responsibilities with the highest possible quality. For over thirteen years, they meticulously honed this approach, transforming the extensive review of annual reports and countless company visits into a finely tuned art.

Richer, Wiser, Happier

In his 2021 book, Richer, Wiser, Happier: How the World's Greatest Investors Win in Markets and Life, William Green dedicates Chapter Six to Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria. Green introduces "Nick & Zak’s Excellent Adventure" and their Nomad Investment Partnership by stating, "A radically unconventional investment partnership reveals that the richest rewards go to those who resist the lure of instant gratification." This profound long-term mindset was instrumental to Nomad's eventual remarkable successes.

Exceptional Performance

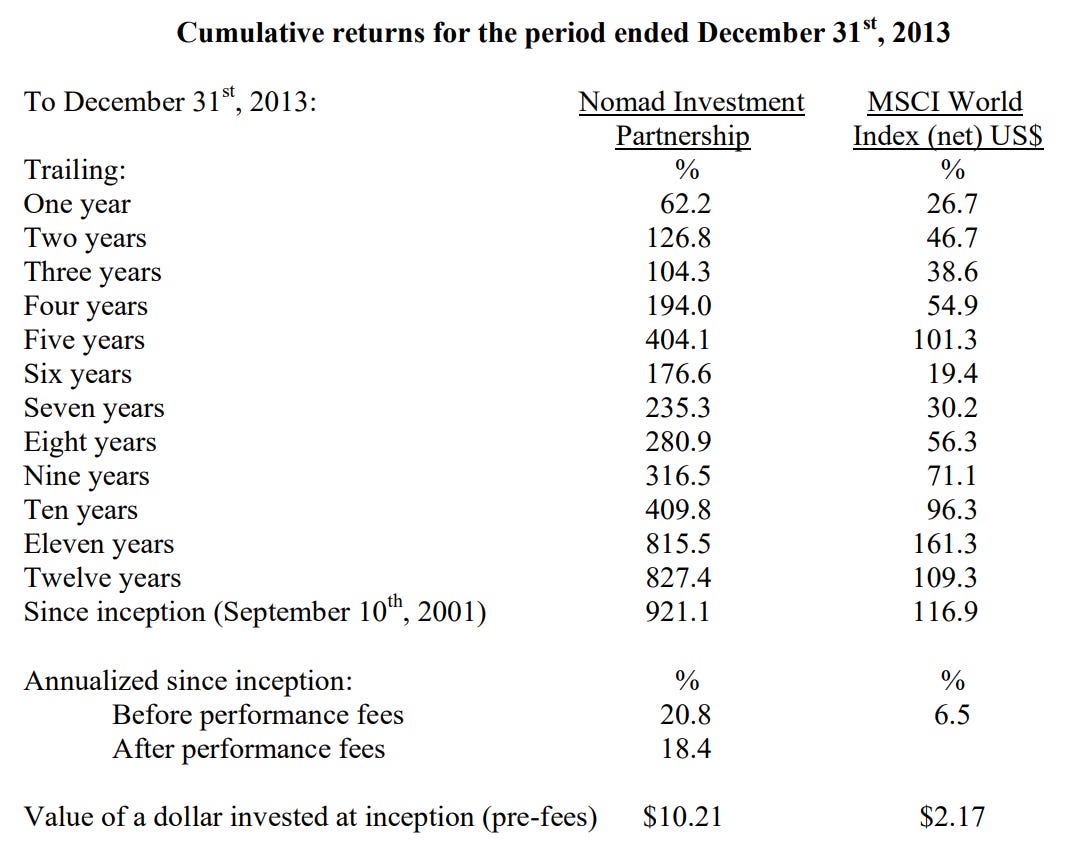

The Nomad Investment Partnership, launched on September 10, 2001, under the aegis of Marathon Asset Management, delivered exceptional returns. Over their thirteen-year tenure as nomads, Sleep and Zakaria achieved a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 20.8% from September 2001 through December 2013. In contrast, the MSCI World Index recorded a CAGR of 6.5% over the same period.

In absolute terms, Nomad generated a 921.1% return, while the MSCI World Index yielded a total return of 116.9%. To illustrate, an initial $100,000 invested in the MSCI World Index would have grown to $216,900, whereas the same investment with Nomad would have expanded to $1,021,100. Even factoring in several percentage points of inflation over this period, Sleep and Zakaria delivered extraordinary growth in purchasing power for their partners.

Absolute Return Fund

In their inaugural letter covering the final months of 2001, Sleep emphasized that Nomad operated as an absolute return fund. While acknowledging that the performance of an index, specifically the MSCI World Index, was included for contextualizing their own returns, he noted its "short term as it is" relevance. They also articulated an expectation to "handsomely" outperform the index over time, yet clarified this would merely be a byproduct of their primary "absolute return orientation."

Global Nomads

During its formative years, Sleep and Zakaria traversed the globe in pursuit of superior investment opportunities. By the close of 2001, Nomad's portfolio comprised 18 investments across 16 distinct sectors. Geographically, the allocation was diversified across Southeast Asia (32.8%), North America (23.6%), Europe (12.7%), and other emerging markets (2.9%).

A critical aspect of their investment process was valuation. Companies were required to trade at approximately half of Sleep and Zakaria's calculated intrinsic value. This valuation discipline, coupled with a strong emphasis on management quality and capital allocation decisions, provided Nomad with a material advantage. Sleep noted the rarity of finding all three components—undervaluation, strong management, and sound capital allocation—in a single investment. Their distinctiveness was further amplified by adopting a genuinely long-term investment horizon, differentiating them from most other funds.

Nomad’s orientation is genuinely long term, [...] we are looking for businesses trading at around half of their real business value, companies run by owner-oriented management and employing capital allocation strategies consistent with long term shareholder wealth creation.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2001)

Portfolio Companies

What types of companies populated Nomad's early portfolio? In their first letter (2001), Sleep and Zakaria detailed two positions: International Speedway (United States), which operated twelve race circuits at the time, and Matichon (Thailand), then Thailand's second-largest newspaper. A brief exposition of the latter follows below.

Matichon

As of December 31, 2001, Matichon constituted a 3.2% weighting within Nomad's portfolio. In my view, such foreign investment propositions warrant a high degree of caution. Firstly, one might contend that superior qualitative investment opportunities could exist elsewhere, necessitating consideration of opportunity costs. Secondly, due to limited local market knowledge, which one might not effectively or efficiently acquire, opportunity costs related to time investment are also a factor. Thirdly, the inability to speak the local language precludes direct assessment of the company's output and content quality. As Peter Lynch famously advised, "Invest in what you know." This principle, for many, would not extend to a Thai publisher.

Nevertheless, Sleep and Zakaria allocated partnership capital to this Thai publisher, perceiving value where others did not. Although they could not read the newspapers themselves, they relied on trusted Thai acquaintances for editorial content assessment. The company was also seen as distinct from its market-leading competitor, characterized as more "old Thailand," thus appealing to a younger demographic. This was evident in rising circulation figures post the 1997 Asian crisis.

Matichon's share price had fallen from TB300 in 1994 to TB50 by early January 2002. Despite a 33% decline in revenue since 1996, cash flow had increased by 40%, and the company traded at a 9% dividend yield, anticipating further cyclical recovery.

While seemingly a classic value play at first glance, qualitative aspects also played a significant role, according to Sleep. The company was family-run, maintained a strong focus on its core business, and prioritized long-term survivorship by consciously keeping its newspaper prices low.

The firm is family run and has avoided the pitfalls of straying into new media or gambling on new titles. Instead, the firm has focused on raising longer term readership and margins. In an effort to promote circulation the cover price has been kept low [...].

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2001)

Unbeknownst at the time that this would become a hallmark of Nomad, the final statement laid the groundwork for one of their core principles: investing in companies willing to accept lower short-term profits to enhance their long-term longevity.

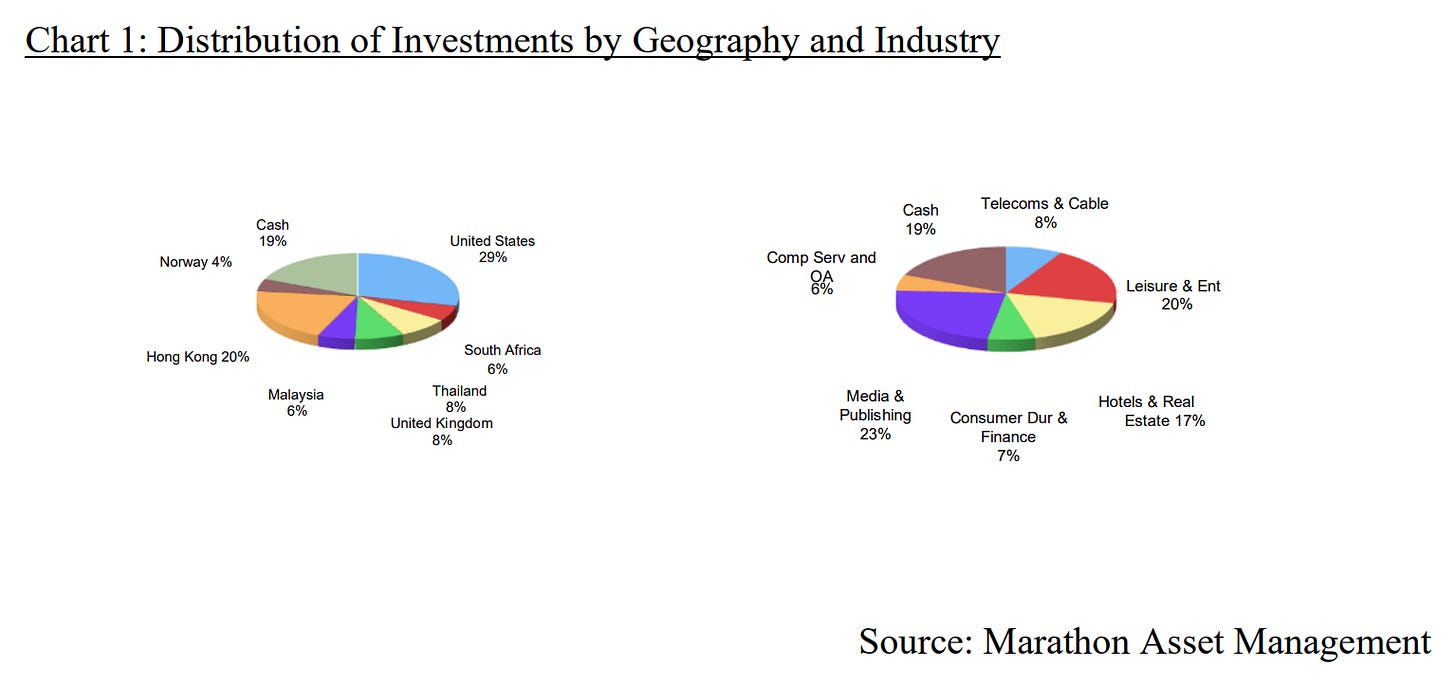

Nomad's letters consistently featured detailed insights into select portfolio positions, elucidating the investment thesis behind them. The Interim Report of 2002 further included the diagrams below, providing an overview of Nomad's early portfolio composition.

In addition to these geographical and industry breakdowns, Nomad also categorized its holdings thematically. As of June 30, 2002, approximately 37% of Nomad's portfolio comprised "quality, difficult to copy, franchise operations." This category included businesses such as newspapers, television stations, racetracks, consumer brands, and casinos. Furthermore, 27% of the invested capital was allocated to "discounted asset-based businesses," encompassing real estate, hotels, and conglomerates where fixed assets or cash balances represented a significant portion of the appraised value. Finally, 17% of the capital was deployed in companies Sleep and Zakaria believed were in temporary distress, characterized by declining revenues and profits.

“[...] our results have been achieved the old-fashioned way, through buying securities in reasonable businesses at discounted prices.”

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2002)

The Error of Omission in Value Investing

The emphasis on valuation was often quantified as a percentage by Sleep and Zakaria, expressing the current market value of an individual company—or the entire portfolio—as a percentage of their estimated intrinsic value. By the end of June 2002, Sleep reported this figure to be 51% of the estimated fair value of Nomad’s portfolio. However, what Sleep and Zakaria initially overlooked was that a company could continue to generate substantial additional intrinsic value even after reaching their perceived 100% threshold.

Our aim is to make investments at prices we consider to be fifty cents on the dollar of what a typical firm is worth.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2003)

A clear illustration of this insight emerged from their value play in the British company Stagecoach, which by late 2002 had become Nomad's largest portfolio position. Stagecoach, the United Kingdom's largest bus operator, also held international operations. The anticipated catalyst for their investment was the expected divestiture of non-core business units. Nomad estimated Stagecoach's intrinsic value at approximately 60 pence per share, leading Sleep and Zakaria to acquire shares in November 2002 at a market price of 14 pence. By the close of 2003, these shares had appreciated six-fold. Yet, Sleep and Zakaria would later reflect on this as their most significant error: they sold the shares far too early.

By the end of 2002, Nomad's portfolio contained 25 companies spread across 8 countries. By mid-2004, this number had increased to over 30 companies, with individual position weightings ranging from 0.3% to 7% of the total portfolio. The large differences in the weightings of their holdings were a result of their strong commitment to price discipline: "A consequence of price discipline is that one cannot be certain of the size of the investment opportunity in advance." (Nomad Investment Partnership, 2004).

At Nomad we have as broad an investment mandate as possible, which has allowed us to make investments as diverse as the preferred shares of a US technology business (Lucent), the common equity of a Scandinavian newspaper business (Schibsted), unlisted UK equity (Weetabix), a small capitalisation Thai newspaper (Matichon), a South African casino (Kersaf), a Hong Kong mobile phone operator (Smartone) and even a large US discount retailer (Costco). This breadth of scope is why we named the Partnership “Nomad”.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2003)

Investable Universe

At Nomad's inception, Sleep and Zakaria truly embodied the term nomads in the broadest sense, reflected in their expansive view of financial markets. Beyond equity investments, they also attempted to acquire bonds in their early years that they deemed traded at a significant discount to par value. However, this endeavor was ultimately unsuccessful, as one of the target companies aggressively repurchased its own bonds from the market.

Sleep articulated that he did not view this as an issue but rather lauded the action. He believed it created value for the company's shareholders—among whom Nomad was counted—by demonstrating management's composure during turbulent times.

It is important to note that Nomad strictly confined itself to the domains of equities and bonds. A remark from Sleep explicitly clarifies this stance:

If we ever write to you asking for permission to invest in any of the above [leverage, shorting, contracts for difference, options, synthetic structures] sell your shares. And call us to sell ours. Nomad is not a hedge fund, it is an Investment Partnership, and the results below have been achieved without the investment Viagras that have become so popular with the get-rich-quick-crowd. The results have been earned the old-fashioned way, through contrarian stock picking.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2003)

Weetabix Limited

In the first half of 2003, Nomad secured permission to invest in unlisted companies. This was with the express intent of acquiring a stake in Weetabix Limited, a prominent UK manufacturer of breakfast cereals and bars. Weetabix shares were traded on Ofex, which initially placed them outside Nomad's established investment parameters.

Despite Weetabix's 22% market share—which one may deem low and, due to its non-monopolistic character in a commodity-like industry, might not compose the power of a competitive advantage—Sleep and Zakaria identified significant value in the company. They highlighted, among other factors, the heavy investment in its brand names through advertising and marketing, which the then-chairman referred to as an "investment in the future"—a fundamental aspect of effective marketing. This contrasted sharply with some of Weetabix's competitors, who, according to Sleep, were focused on cost reduction to meet short-term Wall Street earnings expectations. Consequently, Weetabix's share of voice (its proportion of market-wide marketing expenditure) exceeded its actual market share.

Value creation is often most sustainable when it is built slowly, and notably last year Weetabix became the largest selling breakfast cereal, overtaking Corn Flakes seventy years after the company’s foundation.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2003)

Sleep also noted that the company maintained a 50% overcapacity in its factories to maintain production standards and delivery reliability.

Nomad acquired Weetabix shares at approximately £20 in the first half of 2003. By the end of that year, Weetabix received a takeover bid of £53.75 per share from the private equity firm HM Capital (then operating as Hicks, Muse, Tate & Furst Incorporated).

Despite the celebratory mood among many of Nomad's partners, Sleep and Zakaria did not share the same enthusiasm: they believed the takeover bid did not align with the company's intrinsic value. More on that particular aspect will be discussed later.

Chapter 2 | Super High-Quality Thinkers

In 2004, Sleep first articulated the concept of "super high-quality thinkers": companies that consistently outmaneuver their competitors and rigorously allocate capital to reinforce their competitive advantages.

In the office we keep a list of companies assembled under the title “super high-quality thinkers”. This is not an easy club to join, and the list currently runs to fifteen businesses. [...] They have chosen to out-think their competition and allocate capital over many years with discipline to reinforce their firm’s competitive advantage. [...] This list is a group of wonderful, honestly run compounding machines. We call this the “terminal portfolio”. This is where we want to go.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

Sleep then addressed why Nomad's current portfolio did not align with this list of super high-quality thinkers. The reason was clear: price was the primary impediment.

In paying up for excellent businesses today, investors are already paying for many years growth to come, in the hope that, as the saying goes, “time is the friend of a good business”. [...] Those that chase high prices today, leave less gunpowder for the future. In effect, they value future opportunities close to nil. So, opportunity cost is partly behind our decision as well.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

However, Sleep noted that such high-quality businesses could, in fact, also trade at more attractive valuations during periods of irrational pricing, such as market corrections or macroeconomic crises:

Today, we have made two investments in wonderful compounding machines, and only one of those is meaningfully represented in the portfolio (Costco Wholesale). What is the probability that say, over the next ten years, a good portion of these “super high-quality thinkers” will be priced at 50c? Our betting is that the odds are reasonable. Even though prices are generally high, the trick is to do the work today, so that we are ready.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

This underscores that while Sleep and Zakaria desired to incorporate these high-quality companies into Nomad's portfolio, they would only do so when the valuation was appropriate.

Recognizing their lack of control over the daily market prices of these shares, they focused on what they could control: conducting thorough research on these companies, even if their current valuations were deemed too high. This proactive approach ensured they were well-prepared to act swiftly when a suitable opportunity would arise.

I resonate with many aspects of this strategy. For example, earlier this year, I conducted an in-depth analysis of Costco Wholesale, despite its seemingly robust valuation. Acknowledging this, I still chose to invest significant time in a comprehensive study. This process yielded numerous valuable insights, positioning me to act decisively should Costco’s valuation become attractive once more.

Moats & Destinations

The term "moat" first appeared in Nomad's letters at the close of 2004:

Costco has some of these attributes [offering size, offering longevity, offering FCF]. The range of products is as wide as any retailer, and by-passing savings back it is building a formidable moat.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

The qualitative aspects referenced above—pertaining to a company's longevity rather than solely focusing on the delta between current and implied valuation—fall squarely within the domain of moat investing. These may not be the immediate criteria traditional value investors typically prioritize. In my view, this marks a shift in Sleep and Zakaria's focus, or at least in the insights we can derive from their correspondence.

The answer lies in analyzing not the effects and outputs of a business, but, digging down to the underlying reality of the company, the engine of its success. That is, one must see an investment not as a static balance sheet but as an evolving, compounding machine.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

This evolution in thinking is particularly evident in Sleep's description of how he and Zakaria dedicated significant time to contemplating how companies interact with their environment and the implications for their future viability.

We spend a considerable portion of our waking hours thinking about how company behaviour can make the future more predictable and lower the risk of investment. Costco’s obsession with sharing scale benefits with the customer makes that company’s future much more predictable and less risky than the average business and that is why it is our largest holding. Our smaller holdings are less predictable but in certain circumstances could do much better as investments. We are just not sure that they will as their “cone of uncertainty” has a much greater radius than at Costco.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2005)

Here, Sleep indicates that Costco's future predictability and lower risk, compared to an average business, justified its largest weighting in Nomad's portfolio. In the 2005 Annual Letter, Sleep succinctly summarized this point:

Understanding the value of a company involves assessing the likely outcomes given management behaviour and competitive forces and weighing the probable outcomes in a valuation.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2005)

Costco was initially acquired by Sleep and Zakaria in 2002 due to its then-low valuation (~50c on the $1). According to Sleep, this undervaluation stemmed from a lack of investor understanding regarding Costco management's strategy. This interpretation aligns with Sleep's subsequent statements (e.g., "We consider ourselves contrarian, value-based investors. Ordinarily what we are buying is hated and reasonable value.").

However, the delta between market value and implied intrinsic value represents only a limited vacuum within which returns can be generated. Extending one's investment horizon beyond these confines reveals that sustainable returns are derived from a company's underlying value creation far into the future. When management is committed to sustaining this long-term engine, the period for value creation significantly expands.

This naturally leads to the question of what qualitative aspects contribute to this long-term value creation. It was a question Sleep himself posed:

“What characteristics could one bestow on a company that would make it the most valuable in the world?”

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

This question will be the central theme of the next chapter.

Chapter 3 | Quality Attributes

“What characteristics could one bestow on a company that would make it the most valuable in the world?”

Sleep posed this question in the 2004 Annual Letter, and his response centered on the following elements:

Operating a huge market place (offering size): the capacity to operate within a substantial addressable market.

High barriers to entry (offering longevity): the presence of significant deterrents that prevent new competitors from easily entering the market.

Very low levels of capital employed (offering FCF): the ability to generate substantial free cash flow with very low levels of invested capital.

In 2007, Sleep elaborated on these themes, outlining additional principles crucial for successful business scaling:

A company must be able to self finance its growth.

In markets with numerous alternatives, the return on capital must be sustainably high.

A company's barriers to entry—its moat—should strengthen as the business grows (e.g., revenue growth leading to a stronger moat).

Sleep added that he and Zakaria preferred to invest in companies with fundamentally simple structures, avoiding those that would necessitate extensive restructuring for further growth. He emphasized, "[...] it is complexity that is one of the main reasons firms fail as they try to grow."

[...] when this basic building block [simplicity of operations] is combined with the scale efficiencies shared model (which increases the moat as the firm grows), customer centric orientation of the firm’s founder, as well as his healthy disdain for Wall Street, this combination makes us think that we may have a mouse that can turn into an elephant.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

Founder-Led Enterprises

Unbeknownst to them initially, a significant portion of Nomad's portfolio companies were either founder-led or guided by first-generation management. Sleep hinted at a correlation between the desired quality of a company's people (e.g., management and culture) and whether it was founder-led:

[...] we suspect that Nomad portfolio turnover will be particularly low going forward: we are quite happy with what we are currently sitting on. One reason for this is that the fund is overwhelmingly (over eighty-five percent) invested in firms run by their founders or first-generation management. Just as interesting is that Zak and I did not plan for this! We have ended up with a portfolio of owner-managed businesses as a byproduct of our assessment of the quality of the people involved. In other words, these managers earned their way into the portfolio.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

In 2008, amidst the tumultuous credit crisis, Sleep highlighted that 55% of Nomad's portfolio companies were either repurchasing their own shares or had significant insider buying by management.

Almost ninety percent of the portfolio is invested in firms run by founders or the largest shareholder, and their average investment in the firms they run is just over twenty percent of the shares outstanding. Fifty-five percent of portfolio companies are either repurchasing shares or have had meaningful insider buying.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2008)

Compounding Machines

Fundamentally, and assuming a responsible level of debt, companies should consistently reinvest when presented with promising investment opportunities. This holds true even during periods of macroeconomic headwinds, often referred to as "crises" today.

Sleep addressed this in Nomad's 2006 Annual Letter, in response to the fund's underperformance relative to the MSCI World Index that year:

[...] our companies, by and large, are reinvesting heavily in their businesses at a time when the market, taking its cue from the private equity buyers, have rewarded firms with high levels of current free cash flow.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2006)

This pattern was evident, for example, with Amazon in 2022, when its operating cash flows were significantly pressured by increasing capital expenditures (CapEx), resulting in a depressed stock price.

In the same 2006 Annual Letter, Sleep offered a commentary on Amazon that, despite predating the 2022 scenario by fifteen years, reveals striking similarities:

Last year the company [Amazon] reported free cash flow of just over U$500m, indeed it has been around this number for the last few years. What is important is that the U$500m is after all investment spending on growth initiatives such as capital spending, but also research and development, shipping subsidy, marketing and advertising and price givebacks. The firm has been investing in these items today to grow the business in the future so that free cash flow in years to come will be meaningfully greater than it would be otherwise.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2006)

Sleep also included a pertinent quote from Jeff Bezos in this context, which is reproduced below:

Math-based decisions command wide agreement, whereas judgment-based decisions are rightly debated and often controversial, at least until put into practice and demonstrated. Any institution unwilling to endure controversy must limit itself to decisions of the first type. In our view, doing so would not only limit controversy – it would also significantly limit innovation and long-term value creation.

— Jeff Bezos (Amazon Shareholder Letter, 2005)

Following this quote from Bezos's 2005 Amazon Shareholder Letter, Sleep underscored that Bezos would run an exceptional investment fund due to his long-term focus and his willingness to forgo control over the timing of payback periods. Sleep added:

[...] the ever widening of the moat surrounding Amazon largely determines whether our investment will be a success.

This essentially mirrors the approach we advocate within massive moats, prioritizing moats built on customer value creation. When a company's added value (potentially relative to competitors) increases, its moat fundamentally strengthens. This occurred with Amazon in 2005 through further price reductions, which augmented consumer surplus and extended Amazon's prospective runway for continued operations. Here, secular growth and a widening moat converge as the main ingredients of its compounding.

In the deep dive below, I have compiled my research on Amazon.

Culture

The insights discussed previously have an even more fundamental origin: corporate culture. A company's culture significantly shapes the input that drives critical outcomes, such as enhancing consumer surplus through price reductions. Therefore, corporate culture is paramount for long-term success. As Sleep articulated:

[...] culture plays a part in the continuity of a successful price giveback strategy and factors such as culture, because they are hard to quantify, often go undervalued by investors [...].

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2009)

This bond (or not!) between customers and companies is one of the most important factors in determining long-term business success. Recognising this can be very helpful to the long-term investor.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2011)

Consequently, culture stands as a profoundly important qualitative attribute within companies. More on this will be explored later through the example of Costco Wholesale.

Chapter 4 | Long-Term Mindset

Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria established Nomad with a deeply embedded long-term vision from its very inception, a philosophy clearly articulated in their early letters.

One of Nomad’s key advantages will be the aggregate patience of its investor base. [...] If Nomad is to have a competitive advantage over our peers this will come from the capital allocation skills of your manager (if any) and the patience of our investor base. Only by looking further out than the short-term crowd can we expect to beat them. It is for this reason we named Nomad an Investment Partnership and not a fund. The relationship we seek is quite different.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2002)

In the near term our results are as likely to be bad as good, but we are confident that in the long run they will prove satisfactory.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2002)

For instance, in their Interim Letter of 2002, just nine months after Nomad's founding, they referenced a 1960 letter from Warren Buffett. In it, Buffett discussed the expectations investors should hold regarding their investments and the associated financial performance.

Buffett contended that even with the prospect of superior returns, investors should not anticipate a relatively constant outperformance of the market average. Instead, he deemed it probable that any alpha would manifest through better-than-average performance in stable or declining markets, and average to potentially worse-than-average performance in rising markets (Warren Buffett, 1960).

Pay No Attention

They also referenced Fred Schwed's (2005) Where Are the Customers’ Yachts?, which argues against paying undue attention to extreme market fluctuations and suggests that rational investors might miss certain segments of a bear or bull market. Sleep added that many investors are "professionally required to pay attention."

In my view, Sleep skillfully synthesizes various elements I've also frequently discussed in the past: the incentive fund managers face—both in terms of status and compensation—to maintain the impression of continuous engagement with market developments. In my opinion, true differentiation comes from disregarding the short term and focusing precious time on long-term trends.

Furthermore, Sleep contextualizes Schwed's words within stock price reactions when companies temporarily exhibit lower profitability due to investments in long-term value creation. His message is unequivocal: disregard short-term reactions to quarterly earnings when a company deliberately invests in its future, even if it impacts short-term profits.

For long-term investors, their short-term expectations for stock price movements are therefore irrelevant.

[...] we do not have the faintest idea what share prices will do in the short term — nor do we think it is important for the long-term investor.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2003)

A stoical disposition to short-term results is both the right way to think (never mark emotions to market) but it also prepares one for results that may be reasonable but are unlikely to be an extrapolation of the last two years.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2003)

In their 2008 letter, Sleep indicated that he and Zakaria pursued a "road map" where the original purchase price would ultimately become inconsequential if the growth in underlying value propelled the acquisition to become one of the greatest investments of all time.

A long-term horizon is also one of the most critical variables for enabling thought in terms of value creation mechanisms based on shared scale efficiencies; i.e., Scale Economies Shared.

Chapter 5 | Scale Economies Shared

As enterprises grow, their profitability generally increases. This is not solely due to an absolute rise in profits from higher revenue, but also from an expanding profit margin, as fixed costs tend to increase at a relatively slower rate than revenue.

Depending on the shape of their growth trajectory, companies can increasingly leverage their expanding scale. These benefits are commonly referred to as scale economies. While companies can choose to retain these scale economies, they also have the option to (partially) pass them on to their customers.

The practice of sharing these scale economies is exceptionally powerful, precisely because few companies adopt this approach. In 2004, Sleep elaborated on this in the context of Costco Wholesale:

In the office we have a white board on which we have listed the (very few) investment models that work and that we can understand. Costco is the best example we can find of one of them: scale efficiencies shared. Most companies pursue scale efficiencies, but few share them. It’s the sharing that makes the model so powerful. But in the center of the model is a paradox: the company grows through giving more back. We often ask companies what they would do with windfall profits, and most spend it on something or other, or return the cash to shareholders. Almost no one replies give it back to customers – how would that go down with Wall Street? That is why competing with Costco is so hard to do. The firm is not interested in today’s static assessment of performance. It is managing the business as if to raise the probability of long-term success.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

Costco Wholesale

Costco was first mentioned by Sleep in 2002, where he reviewed the retailer's fiscal year 2001 results. In that year, the company generated $35 billion in revenue. For fiscal year 2024, revenue exceeded $254 billion, reflecting a 9% CAGR over this 23-year period.

The quality attributes Nomad ascribed to Costco related to the company's increasing scale economies and its remarkably simple yet honest business model:

This is a very simple and honest consumer proposition in the sense that the membership fee buys the customer's loyalty (and is almost all profit) and Costco in exchange sells goods whilst just covering operating costs. In addition, by sticking to a standard mark-up savings achieved through purchasing or scale are returned to the customer in the form of lower prices, which in turn encourages growth and extends scale advantages.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2002)

This business model remains exceptionally successful 23 years later. At the time, Nomad explicitly focused on Costco's Total Addressable Market (TAM). In 2002, Sleep noted that Costco operated 284 locations in the United States and 14 in the United Kingdom. Nomad estimated potential growth to 1,000 stores in the U.S. and 200 in the U.K.—though Sleep added, "planning regulations may not allow for this." Sleep further stated:

At U$30 the firm is valued as a cash cow, with higher levels of profitability (as capacity utilisation increases) and modest levels of growth justifying a valuation over U$50 per share. Costco is as perfect a growth stock as we have analysed and is available in the stock market at a close to half price.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2002)

(As of January 1, 2025, Costco operates 617 stores in the United States and 29 in the United Kingdom.)

In the deep dive below, I have compiled my research on Costco Wholesale.

A Deep Dive Analysis into Costco Wholesale Corporation

Costco Wholesale's strategy can be summarized as follows: offering a quality assortment of products at the lowest possible price to its members—who pay an annual membership fee—while operating cost-efficiently and aiming for high inventory turnover. The company minimizes its profit margin on merchandise to create the highest possibl…

In the 2008 Annual Letter, Sleep posited that companies sharing their increasing scale economies with customers can thrive even during challenging economic times:

Scale economics works well in bad economic times as well as good.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2008)

Nomad’s firms are, on average, so cost advantaged compared to many of their competitors that the worse it gets for the economy, the better it gets for our firms from a competitive position.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2011)

Building strong customer loyalty plays a crucial role here. Value creation for these enterprises primarily occurs at the business level through volume growth. In Costco's case, retaining existing members is vital, as membership fees contribute significantly to the company's value creation, and by extension, to its shareholders.

Scale economics shared incentivises customer reciprocation, and customer reciprocation is a super-factor in business performance.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2008)

The whispered voice of price givebacks is economically fruitful but only if the customer reciprocates in the form of more spending, even in the face of more promotional approaches by competitors.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2009)

By June 30, 2009, over half of Nomad's portfolio consisted of companies within the "scale economies shared" theme.

In 2010, Sleep recounted their visit with Jim Sinegal, then CEO of Costco. While walking the aisles, Sinegal handed Sleep and Zakaria a memo penned by Sol Price, the founder of Fed-Mart. The memo read:

Although we are all interested in margin, it must never be done at the expense of our philosophy. Margin must be obtained by better buying, emphasis on selling the kind of goods we want to sell, operating efficiencies, lower markdowns, greater turnover, etc. Increasing the retail prices and justifying it on the basis that we are still “competitive” could lead to a rude awakening as it has with so many. Let us concentrate on how cheap we can bring things to the people, rather than how much the traffic will bear, and when the race is over Fed-Mart will be there.

— Sol Price

Sleep described Sol Price's memo as "The best summary of the business case for scale economics shared we have come across." In his elaboration following this memo, Sleep alluded to what I believe is one of the most critical qualitative characteristics of companies: their internal culture—the DNA.

Forty-three years later, almost to the day, and Costco is the most valuable retailer of its type in the world. Cultures that care about the little things all the time are very hard to create and, in the opinion of Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, almost impossible to create if not put in place at the firm’s genesis.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2010)

This strongly reminds me of the Dutch retailer Action, in which the British private equity firm 3i Group is a major shareholder. At Action, cost awareness is deeply embedded in the company’s DNA. Consider, for example, the maximum amount employees are allowed to claim for hotel stays, or the strict, intangible boundaries applied during procurement negotiations. This corporate culture enables Action to maintain sales prices that are significantly lower than those of its competitors: based on price comparisons across 1,500 to 2,000 SKUs, competitor prices were 58% to 95% higher in the fourth quarter of 2024.

In the deep dive below, I have compiled my research on 3i Group.

Without a strong corporate culture, the probability of sustainably delivering exceptional performance is very low. Thus, a company's culture serves as a continuous input variable for the moat it can build over the long term.

[...] one reason he [Jeff Bezos] prefers Amazon to be a large company with small margins is that if he shares the efficiency benefits that come with growth with his customers, he turns size, frequently an anchor on business performance, into an asset. In other words, the moat surrounding the firm deepens as the firm grows.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2011)

Robustness Ratio

In the 2005 Interim Letter, Sleep revealed that he and Zakaria employed the Robustness Ratio as a framework to assess the magnitude of a company's moat. This ratio compares the consumer benefit (the value saved by customers) against the company's own profit; the portion available to shareholders after employee compensation. Sleep cited a consumer benefit of $5 for every $1 of profit retained by Costco.

At Costco we think the customer saving is around five dollars, compared to shopping at most supermarkets, for every dollar retained by the company. [...] Look around you. How many companies save five dollars for their customers for every one dollar they keep? While the standard Wall Street view is that such a picture is retailing’s equivalent of collectivism, in our view it represents an excitingly wide and unassailable moat.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2005)

Sleep clarified that this ratio is not a magical formula for moat measurement but serves as a valuable indicator for identifying moat-possessing companies and their long-term longevity:

Where robustness comes into its own is in identifying companies, such as Costco, which may be under-earning when compared to their potential. This generates super long-term investment opportunities for those willing to look beyond reported earnings.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2005)

The core principle here is finding the optimal balance for all stakeholders. For instance, young companies early in their lifecycle might choose to prioritize additional value creation for their customers by accepting lower short-term profits. The proportion between consumer benefit and the company's own value creation can then achieve a more sustainable equilibrium at a later stage.

Ultimately, Sleep contended, the objective for companies is to extend their lifespan, despite the pervasive temptations of short-term gratification. Given the myriad incentives in financial markets, coupled with the short-term-oriented primal instincts in our own DNA, true "scale economies shared" businesses remain a rare phenomenon.

Scale Economies Shared by Nomad

Sleep and Zakaria also applied this very concept within their own firm by implementing a variable management fee. While this fee remained constant in absolute terms, it declined as a percentage as assets under management (AUM) increased. In my view, this exemplifies the high moral and qualitative standards Sleep and Zakaria espoused.

As the Partnership grows in size the management fee will decline as a percentage of assets and, that way, all investors share in the natural scale economics of the operation.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2006)

Chapter 6 | Portfolio Management

For advanced investors, determining portfolio concentration represents one of the most critical aspects of portfolio management. This involves addressing questions such as the optimal number of holdings for an ideal risk-return profile, as well as establishing individual position weightings.

A clear shift in Sleep and Zakaria’s approach to portfolio concentration is visible over the years. In Nomad's nascent period, the portfolio was significantly less concentrated than in its later active years. A brief timeline of Nomad’s portfolio development follows below. (For an overview of Nomad's early years, please refer to Chapter 1.)

2004

By late June 2004, Nomad's portfolio comprised over 30 investments, each weighted between 0.3% and 7% of the total, with a cash position of 16%. In their 2004 Interim Letter, Sleep articulated their considerations regarding portfolio allocation:

In our opinion, the massive overdiversification that is commonplace in the industry has more to do with marketing, making the clients feel comfortable, and the smoothing of results than it does with investment excellence.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

2005

As of December 31, 2005, Nomad's portfolio consisted of approximately 24 equities. The top 10 positions accounted for roughly 70% of the total. Notably, 6 of Nomad's portfolio companies received takeover bids in the preceding 18 months, indicating the undervaluation implied by Sleep and Zakaria. In other words, other corporations and private equity firms also recognized this undervaluation.

2006

By December 31, 2006, the 5 largest holdings collectively constituted 50% of the total portfolio, while the top 10 represented 75%. Sleep remarked:

The polarity of the portfolio, with several large, simple, high conviction holdings, and a tail of more complicated and less certain ideas (but which may have more upside) is likely to be a feature of Nomad for some time.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2006)

For the year 2006, Sleep continued to express the value of Nomad's holdings based on their estimated intrinsic value, which then stood at the upper end of 60 cents on the dollar.

2007

As of June 30, 2007, the 10 largest holdings represented over 80% of the total portfolio. This year, Sleep also introduced the concept of inverting portfolio construction. Instead of starting from a 0% initial weighting and gradually building a position to a few percentage points based on conviction, he proposed beginning from a hypothetical 100% weighting.

Sleep conceded that, in hindsight, Nomad’s initial weighting in Amazon was too low. Ultimately, the returns investors achieve are significantly determined by the chosen weightings and the proportional allocation to the best performing businesses within the portfolio.

2009

By June 30, 2009, Nomad had approximately 75% of its portfolio invested in growth companies, with one single company accounting for 30% of the total. Over 50% was in "scale economies shared" businesses, and just under 10% in "super high-quality thinkers." The remaining 30% was equally divided between "discounts-to-replacement-cost-with-pricing-power" and "hated-agencies." Nomad then held 20 investments, with the top 10 positions representing approximately 80% of the portfolio: "Today we have a portfolio of exceptional, iconoclastic businesses that we could own for many years." (2009).

2011

As of December 31, 2011, Nomad's portfolio consisted of 10 companies. Amazon's contribution to Nomad's success was substantial; at one point, Amazon grew to approximately 40% of Nomad's total invested capital, driven by a tenfold increase in the company's market capitalization since 2005.

2014+

Following the termination of the partnership, Zakaria reportedly acquired around 6 companies for his personal portfolio. Amazon ultimately became his largest position, and represented approximately 70% of his total assets.

In his book Richer, Wiser, Happier (2021), William Green notes that Zakaria has, at the time, never sold any Amazon shares from his personal portfolio. The value of his other positions was almost entirely allocated to Costco, Berkshire Hathaway, and the online retailer Boohoo.com, according to Green.

Sleep reportedly concentrated almost his entire wealth in 3 companies: Amazon, Costco, and Berkshire Hathaway. In 2018, he eventually sold half of his Amazon stake (which also represented approximately 70% of the total at that time). When Green spoke with Sleep again in 2020, Sleep indicated that he had reinvested the millions in proceeds into a fourth position: ASOS, a British online retailer. Following his purchase, the stock initially doubled rapidly. However, examining ASOS's share price performance since 2021 reveals a decline of over 90%—hopefully, Sleep anticipated the changing business case in a timely manner.

(The data cited in the "2014+" paragraph above are based on information presented in William Green's book Richer, Wiser, Happier: How the World's Greatest Investors Win in Markets and Life (2021)).

Chapter 7 | Psychology & Emotions

The preceding chapters have distilled key lessons from Sleep and Zakaria's investment evolution—from initial value plays to a qualitative, buy-and-hold approach—covering fundamental company attributes, long-term thinking, concepts like scale economies shared and the robustness ratio, and portfolio management and concentration.

This chapter delves into the crucial lessons learned regarding the emotional dimension of investing, focusing on behavioral and psychological aspects. This domain is arguably as vital as the financial considerations.

Acknowledging Errors

Merely nine months after its inception, Nomad executed its first sale: Monsanto was divested following an analytical error by Sleep and Zakaria. To transparently address this misstep, they dedicated a full passage in their 2002 Interim Report to their oversight: "That way you will be under no illusion about the fallibility of your manager."

This resonates deeply with me. In an environment where incentives often compel publicizing successes and concealing setbacks, I personally strive to regularly reflect and openly share my own mistakes. This is in the hope that the next generation of investors will be better prepared and more quickly identify the optimal path forward.

Navigating Adversity

Early in the partnership, Nomad faced a setback with a bankruptcy within one of its holdings: Conseco filed for bankruptcy in December 2002.

Investment mistakes are inevitable and indeed to some extent desirable, and we have no interest in hiding them from you (or in portfolio window dressing) — as they say, it is what it is.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2002)

During Nomad's active period as a partnership, the global credit crisis became a central challenge. Reflecting on the first half of 2008's results, Sleep remarked:

“Even though the partnership has lost money so far this year, Zak and I have almost no stress from investing.”

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2008)

And further:

We would counsel you to think about the inputs to investing rather than the outputs. It is in times like these that the hard psychological and analytical work is done and the partnership is filled with future capital gains: this is our input. The output will come in time. Those with a rational disposition may not find it too hard to feel good today.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2008)

Ultimately, investing is about enhancing our purchasing power over the long term. Transient volatility and disruption are an inherent part of this journey. Therefore, it is imperative that we maintain a long-term perspective during turbulent periods.

In 2008, the value of Nomad's holdings declined by 45.3% (MSCI World Index: -40.7%)—nearly a halving. Over the period from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2008, Nomad achieved a cumulative return of +0.4% (MSCI World Index: -2.5%).

How would we, as relatively new investors—having entered what appears to be an endless bull market that, when zoomed out, seems to move in a straight line upward—react if our invested capital were to halve, and five years of accumulated gains vanished instantly?

In such moments, everything hinges on a sound mindset and a robust emotional foundation. As preparation is better than cure, I believe we would be well-advised to train ourselves in emotional intelligence and knowledge to better withstand such scenarios: "I doubt that worrying is the solution to anything particularly: far better planning." (Sleep, 2008).

Whether business values rise faster than share prices, or share prices fall faster than business values, either way the effect is the same: a growing differential between the price of a business in the stock market and its real value. [...] It may not feel like it but, in many respects, these are the best of times for an investor.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2008)

Precisely these moments offer opportunities for those willing to adopt a long-term perspective. If the future destination of companies in our portfolios and on our watchlist remains unchanged, periods of market chaos are, in fact, windows of opportunity. These companies will maintain their strategic focus and make sound decisions even under challenging circumstances, including continuing to invest to enhance the value they provide to their customers.

It is an interesting subconscious psychological tendency that truths are often spoken with a whispered voice whilst shaky suppositions are shouted for all to hear. [...] it is curious that this quiet attitude extends, in its own way, to the companies in which we have entrusted your dollars: Amazon and Costco do not advertise (no shouting here); Berkshire Hathaway and Games Workshop do not provide earnings guidance (popular with baying fund managers and stockbrokers); Amazon, Costco, AirAsia, Carpetright, and parts of Berkshire give back margin to the customer, we would argue that is a pretty humble strategy too.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2009)

In 2008, the Nomad Partnership experienced only 2% net redemptions. This demonstrates that Nomad truly attracted the partners it deserved. Sleep aptly concluded his 2008 letter with the words, "Take heart and look to the horizon." Nothing to add.

Takeover Bid? No Celebration for the Long-Term Investor

Sleep and Zakaria received numerous congratulations from their partners when HM Capital launched a takeover bid of £53.75 per share for Weetabix. However, for the founders, there was no celebratory mood; they believed the offer did not align with the company's intrinsic value.

Whilst we have a profit on our investment in Weetabix, shareholders should be careful what they wish for. Before congratulations are in order, Partners need to weigh in their minds short-term profits against value forgone in the discounted offer price and the incentive provided by the success of seizure for potentially more of the same in the future.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2003)

Sleep described his attempts to contact Weetabix's chairman and investment bankers as "A cry in the dark," lamenting, "Our shareholding is too small to make a difference to the outcome."

Our view is that the discount that the shares trade at in the market is an asset to be harvested for the benefit of all shareholders through share repurchase. But human nature being as it is, insiders will be incented by the low valuation to buy the shares for themselves.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2003)

In 2005, Sleep even characterized a potential buyout of Costco as "theft," given the company's vulnerability due to its then-low valuation:

This is a huge source of risk for current shareholders since being taken out at a low-price amounts to theft.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2005)

Takeovers can indeed effectively steal long-term value creation from smaller shareholders when larger, often institutional, shareholders acquiesce to a takeover premium. In 2006, Sleep reflected on the Weetabix case, sharply criticizing many fund managers:

Many fund managers would rather sell your shares for a small takeover premium now (and market their short-term performance to new investors) whilst turning a blind eye to the doubling in the value of the sold business over the next few years. It’s a scandal.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2006)

Therefore, avoid viewing a quick takeover premium of several dozen percentage points as a success when you are a long-term investor in a company. While it may confirm that a company holds more value than other market participants recognize (in a market where, daily, as many people choose to sell a stock as are willing to buy it, as expressed in units transferred), it remains essential to measure success by long-term indicators (i.e., your annualized return over 5+ years).

Your Stocks Are Not Your Children

In 2004, Sleep articulated that stocks are not like children:

[...] stocks are not like children. The more stocks you own the less you care about each one individually. Attention paid to corporate governance, capital allocation, incentive compensation, accounting, and strategy has to be diluted as the number of stocks rises.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2004)

With this statement, Sleep suggests that the more stocks one owns, the less attention, on average, is paid to each individual holding—unlike with children. This is logical to a degree: the "benefit" of diversification is risk dispersion. However, this can also lead to a diversification of time, potentially fostering complacency in diligently monitoring companies, critically evaluating management's strategic decisions, and fully comprehending the future trajectory of these enterprises.

Don't Be Swayed by the Benchmark

Beyond rational and analytical considerations, emotional aspects also play a significant role in long-term investing. Many investors will perceive their returns over a given period (e.g., the past year) as a success if they outperform the benchmark. This is often also the prevailing view among other investors.

However, as Sleep wrote in Nomad's Partnership Interim Letter of 2005, we should adopt a more long-term perspective on this:

Following what everyone else is doing may be hard to resist, but it is also unlikely to be associated with good investment results. Zak and I concentrate on the price to value ratio of the Partnership and ignore its performance as much as is practical, and we would encourage you to do the same.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2005)

In other words: don't be rattled by the short-term results of others, and don't be distracted by benchmark performance. The focus should be on the long-term intrinsic value growth of the quality gems in your own portfolio; the share price will ultimately follow.

As ever, a stoic indifference to these short-term steps, both up and down, is the right way to think.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

Volatility

Many investors regard volatility as a primary measure of risk. However, Sleep and Zakaria, much like other notable investors such as Dev Kantesaria, hold a differing view. I, too, prefer to distance myself from volatility as a proxy of risk. Because, why should one allow the (ir)rational short-term behavior of other market participants to influence their perception of risk-adjusted returns? In my opinion, qualitative factors such as a company's culture and moat, combined with its current valuation, constitute the most crucial elements in defining an appropriate risk-return profile.

In 2007, Sleep commented on the weighting of Amazon and its potential volatility within Nomad's overall portfolio:

Be that as it may, one effect of having one sixth of the Partnership invested in a volatile stock, such as Amazon, is that our results will also be more variable over the short term. Please bear that in mind in future performance. The volatility does not bother Zak and me one jot.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

The Real Long-Term Risk

Sleep defines the real long-term risk of over-diversification, alongside, for instance, failing to conduct thorough research on all portfolio companies, as misanalyzing the ultimate destination of these businesses. Contemplating this destination is critical; when investors meticulously undertake this, it will be inextricably linked to their appropriate level of conviction.

Let’s invert for a moment: when we think of our investee companies, the firms which we would quite happily own with no word from them for years are those businesses in which we have the highest confidence of reaching a favourable destination: they are the firms we think we know will work.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

The subsequent task is to discount these envisioned business destinations back to today's necessary inputs. Without sustained correct effort (i.e., culture) and resource allocation (i.e., capital allocation), the probability of reaching that end destination diminishes.

Error of Omission (Continued)

In the 2007 Annual Letter, Sleep reflected on Nomad's premature sale of Stagecoach. These shares were acquired at 14 pence and sold at 90 pence. However, by early 2008, the stock traded at 250 pence—many multiples of the selling price. This error, or rather, a learning opportunity as Sleep framed it, was, in his view, caused by an overly strong anchoring to the original analysis at the time of purchase, instead of contemplating the company's future trajectory. The analytical process was too static; the initial assumptions were not updated in light of changing facts, according to Sleep:

This error was reinforced by misjudgments such as denial (the facts had changed) and ego (we can’t be wrong). There was also an over-reliance on price to value ratio type analysis, which can encourage a tighter range of outcomes than occurs in reality.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

By transforming their error of premature selling into a learning moment, Sleep and Zakaria developed the insight to hold onto truly high-quality compounders, including Amazon. A significant portion of Nomad's 2007 return (+21.2%) was attributable to lessons learned from mistakes made in 2003 and 2004 according to Sleep:

And that is just one year’s gain. If we have really learnt our lesson, then the gains will continue in future years too.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

[...] we have argued that the biggest error an investor can make is the sale of a Wal-Mart or a Microsoft in the early stages of the company’s growth. Mathematically this error is far greater than the equivalent sum invested in a firm that goes bankrupt.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

When we, as investors, remain open to learning from our own mistakes and deliberately view them as opportunities for growth, we create a personal feedback loop that fosters continuous development. Charlie Munger referred to this as becoming a "learning machine":

I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent, but they are learning machines.

— Charlie Munger

The continuous application of new, acquired lessons bore fruit for Sleep and Zakaria: Amazon made a significant contribution to the total absolute return Nomad achieved throughout its existence.

4 Common Errors

In Nomad's 2007 Annual Letter, Sleep shared his perspective on the following four common errors:

Denial: ("the reinvention of reality in the mind because the truth is too painful to bear")

Anchoring: ("a static, historic vision of a problem")

Drifting: ("how small, incremental changes in thinking build into a big mistake")

Condemning or Exalting: ("that disposition stops a lot of rational thought")

In our opinion, the biggest risk in investing is the risk of misanalysis. We seek to control this risk through the quality of our research, especially through applying what we have learnt. The quality of our research-based decisions overwhelmingly determines whether we will do well in the long run. But it has almost no influence over the timing of these results.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2007)

Chasing the new-new

Sometimes, what you are looking for is right under your nose, Sleep noted in 2007, in response to the tendency of many investors—under the guise of diversification or higher returns—to venture far afield in their search for new stocks.

We would propose that if knowledge is a source of value added, and few things can be known for sure, then it logically follows that owning more stocks does not lower risk but raises it!

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2009)

Control the 'Urge for Action'

As a novice investor gains a few years of experience, acquires substantial new knowledge, and hopefully learns from early mistakes, it becomes crucial to navigate towards calmer waters and embrace tranquility. Indeed, once you've built a solid portfolio of high-quality companies, the only way to disrupt their compounding process is to sell them.

Naturally, we must continue to monitor each company diligently. Undoubtedly, there will be instances where a sale is justified. Nevertheless, as we mature as investors, we must adopt a more inactive stance—at least outwardly, in terms of the number of transactions we execute.

The research continues but, as far as purchase or sale transactions in Nomad are concerned, we are inactive. Inactive except, perhaps, for the observation, seldom made, that the decision not to do something is still an active decision; it is just that the accountants don’t capture it. We have, broadly, the businesses we want in Nomad and see little advantage to fiddling.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2012)

Chapter 8 | The End

In 2014, Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria elected to liquidate their Nomad Investment Partnership. In a concluding postamble, the founders cited a confluence of factors influencing this significant decision, including increasing regulatory burdens, the imperative for continuous accountability to evolving stakeholders, and the sense that they had fully maximized their contribution to the investment process.

After all, we had what we needed, just a few superb businesses and we were unlikely to sell any of those to fund the purchase of another cigar butt, Philippine cement company, were we?

— Nick Sleep & Qais Zakaria (2021)

The time and resources liberated from the partnership were subsequently reallocated towards pursuing broader philanthropic objectives. This marked a new venture, as they described it: reinvesting resources for the benefit of others. Throughout Nomad's existence, Sleep and Zakaria generated approximately $2 billion for their partners, predominantly comprised of charitable organizations and educational endowments.

In their final Annual Letter, Sleep emphasized that the returns he and Zakaria achieved with Nomad were not their own creation; rather, they were entirely attributable to the value generation of the underlying companies in which they invested:

As time goes by, the performance that you receive, as partners in Nomad, is the capitalisation of the success of the firms in which we have invested (minus our fees!). To be precise, the wealth you receive as partners came from the relationship our companies’ employees (using the company as a conduit) have with their customers. It is this relationship that is the source of aggregate wealth created in capitalism. [...] All Zak and I have done is catch some better waves and try to ride them to the shore.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2013)

Letter to Warren Buffett

In 2014, Sleep and Zakaria penned a letter to Warren Buffett, expressing their gratitude upon the closure of their partnership. They wrote:

It appears to all the world that the performance that Nomad has enjoyed over the years was created by Zak and me. That is not the case. As time goes by, the performance that our clients have received is the capitalisation of the success of the firms in which we have invested. In other words, the real work is done by you and the good people at Berkshire. The purpose of this letter is to say a very big thank you, and let you know that you have made a real difference.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2014)

The End

As we eventually step away from our final professional roles or transition our built enterprises, and ultimately close our eyes for the last time, we hope to have contributed meaningful value to the world. Sleep and Zakaria, however, suggested that they themselves did not inherently add value through Nomad Investment Partners:

Even so, in aggregate, the fund management function, evened out over all shareholder experiences, does not add value per se: it only shuffles wealth created elsewhere.

— Nomad Investment Partnership (2013)

I respectfully disagree with this assertion. The wisdom shared by Sleep and Zakaria serves as a profound source of inspiration to set our sights far on the horizon and strive to do good in a world increasingly driven by short-term rewards.

Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria, thank you for the wisdom you have shared with the world, upon which we can now build further—in an endeavor to pass on these invaluable lessons to one another and to the generations yet to come.

With immense appreciation and respect,

Eelze Pieters

July 30, 2025

“[...] it is not the money you have, but the choices you make, that count.”

— Nick Sleep & Qais Zakaria

Disclaimer: NFA / E&OE. The information above is provided for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, accounting and/or financial advice. You should consult directly with a professional if financial, accounting, tax or other expertise is required.

So much efforts has gone into this article. Thank you

Extremely qualitative write up, thank you for the work