Welcome to this deep dive into Netflix, Inc., a company that has fundamentally changed how we consume video entertainment. This analysis goes beyond the screen to explore Netflix's journey from a DVD-by-mail service to a global streaming powerhouse. What lessons can we learn from its origin? Furthermore, we’ll break down its financial health, competitive advantages, corporate culture, and future prospects. My goal is to provide a comprehensive look at the business, offering insights into what makes Netflix a prime example of a quality company to follow into the future.

Foreword

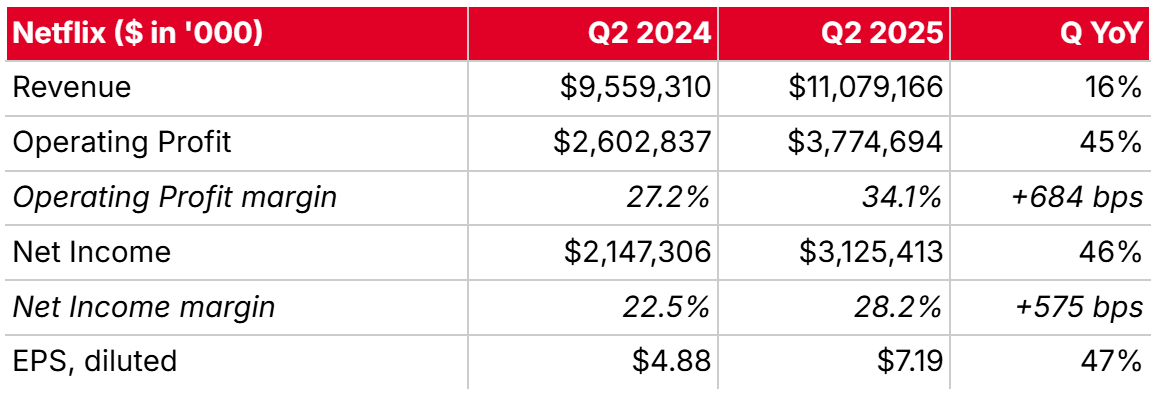

For many, Netflix will need no introduction. The company estimates that it has a global reach of over 700 million people (Netflix, 2025). This number is based on its paying subscribers, which totaled 301.6 million worldwide at the end of 2024. Literally worldwide, as the number of countries where Netflix has launched its platform exceeds 190 (Netflix, 2024).

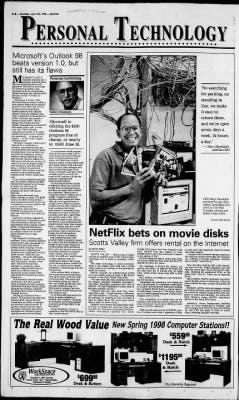

Since the launch of NetFlix.com in 1998, the company has built a rich history full of lessons to draw from. In the 27 years since its founding, Netflix has consistently outsmarted its competition and overcome numerous challenges.

Netflix has dared to take risks by leading with its innovations, without knowing exactly what the future would look like. This was made possible by the people at the company, who have always prioritized the interests of the company, with a mission to make Netflix a success with the best team possible. How the company has done this exactly is explored in this deep dive.

With the transition to streaming that began in 2007, Netflix is now far more than just an internet platform: it is a creator of content that influences our world.

“When our series and films become cultural moments, you can feel it across music, books, fashion, travel and more.”

— Netflix (2025)

In this deep dive, I have compiled the lessons I learned while researching Netflix’s history. I also guide you through the dynamics of the current market in which Netflix operates. Gradually, we work toward the central question: can Netflix continue its success in the future by consistently winning over its customers?

TUDUM — Welcome to the world of Netflix.

I wish you an insightful read,

Eelze Pieters

Augustus 20, 2025

Chapter 1 | The Story of Netflix

Netflix (then called Kibble, Inc.) was founded on August 29, 1997, by Marc Bernays Randolph (1958) and Wilmot Reed Hastings Jr. (1960) in Scotts Valley, California, United States (Netflix, 2022).

To understand how Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings met, we need to go back to the early 1990s, when Hastings, together with Raymond Peck and Mark Box, founded the company Pure Software (Wikipedia, 2025). Hastings co-founded this company at the age of 31, after having worked for several years at Adaptive Technology (Wikipedia, 2025).

Pure Software

Pure Software specialized in designing tools for software error detection. In an interview with USA Today (2006) Hastings stated that he had urged the Board of Directors to replace him with a “real” CEO. Hastings recalled: “I tried to fire myself—twice. I was losing confidence.” The Board of Directors, however, rejected this request, prompting Hastings to remain as CEO, learning the role of CEO on the job.

On August 2, 1995, Pure Software went public, registering a 75% gain on its first day of trading, benefiting from the strong momentum surrounding technology IPOs at the time (Reuters, 1995).

In 1996, Pure Software merged with Atria Software in what Hastings described as “a merger of stars” (TechMonitor, 1996). The deal was valued at over $900 million. Atria Software was valued at approximately 23 times its 1995 revenue of $40 million, while Pure Software had generated $44 million in revenue that same year (The New York Times, 1996). Reed Hastings remained as CEO.

The Meeting

After merging into Pure Atria Corporation, the new company pursued several acquisitions, including the startup Integrity QA, a developer of automated software testing products founded by Marc Randolph along with Steve Kahn and Bob Warfield. Following the acquisition of Integrity QA, Hastings and Randolph found that they were a good match professionally, leading to Randolph being appointed VP of Corporate Marketing.

During their time at Pure Atria, Randolph and Hastings frequently traveled together from Santa Cruz, where they lived, to Silicon Valley. These shared drives provided them the opportunity to discuss various business ideas.

Reed has been working overtime finalizing a huge merger that will put us both out of a job, and once the dust settles from that, I’m planning to start my own company. Every day in the car, I pitch ideas to Reed. I’m trying to convince him to come on board as an advisor or investor, and I can tell he’s intrigued. He’s not shy about giving me feedback. He knows a good thing when he sees it. He also knows a bad thing when he hears it.

— Marc Randolph (2019)

The quote above is from Marc Randolph’s book on the early years of Netflix, That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea (2019).

The huge merger Randolph refers to in the quote was between Pure Atria Corporation and Rational Software. In this deal, Pure Atria was valued at $890 million (The New York Times, 1997), making Hastings a “high-eight-figure guy” overnight. On February 21, 2003, Rational Software was acquired by IBM for approximately $2.1 billion (IBM, 2003), integrating Reed Hastings’ first startup into a major technology corporation.

Only six months separated the acquisition of Integrity QA and the merger between Pure Atria Corporation and Rational Software. According to Randolph (2019), encouraged to further develop Pure Atria’s marketing department, he would have nothing to do in the following four months. This period provided the opportunity to develop new business ideas.

Inspired by Amazon

Inspired by Jeff Bezos and his then-startup Amazon, Randolph pitched countless business ideas to Hastings during their car rides to Silicon Valley. These ideas ranged from customized baseball bats to personalized shampoo by mail. Marc Randolph would later describe that a good idea is often preceded by thousands of bad ones.

During this time, Hastings was busy with the merger with Rational Software and simultaneously making plans to return to Stanford to pursue his passion for education. Despite this, Randolph sensed that he could attract Hastings as an investor if he came up with a compelling business idea.

A valuable entrepreneurial lesson is demonstrated by Randolph's desire to retain the people he had gathered around him during his time at Borland International and Visioneer. Randolph stated, "When you find people as capable, smart, and easy to work with as Christina and Te, you need to keep them around" (2019). Together with them, Randolph began researching and brainstorming on the whiteboards at Pure Atria.

Ultimately, on a car ride to the office, the topic of video tapes came up—Randolph had watched a worn-out copy of Aladdin the night before to get his 3-year-old daughter to sleep, and Hastings had recently paid a $40 late-return fee at Blockbuster for the movie Apollo 13. Randolph, Christina, and Te then proceeded to develop this idea further.

That will never work

At the time, Blockbuster had a ubiquitous presence with over 4,500 stores across the United States. With this in mind, the team would face other obstacles. For example, the high cost of two-way shipping for a bulky VHS tape—to send it to the customer and then have it returned. This was a point of discussion even at Randolph's home with his wife, Lorraine, who laughingly said, "That will never work."

In the summer of 1997, 10 months before launch, they continued brainstorming this idea after Hastings mentioned another high late fee he had received. DVDs, then a brand-new technology in the early stages of customer adoption in the U.S.—prior to 1997, DVDs were only available in Japan—were introduced into their brainstorming sessions.

To test if a DVD could be shipped by mail, Randolph and Hastings bought a CD, which had a similar physical design, and a pink "Happy Birthday" envelope, to send in the CD. Their test was a success: the CD arrived intact. However, this was largely due to luck; the first DVDs they would ship in the early days of Netflix would cause many processing problems or even break (Brainz Magazine, 2022).

Around the same time, during his Stanford period, Reed would act as an angel investor. They estimated that it would require $2 million to bring the idea to life, launch the company, and provide enough runway until the next funding round. With 70% of the shares going to Reed Hastings (who contributed the $2 million) and 30% to Marc Randolph (who contributed his time), Kibble Inc. was founded on August 29, 1997.

Many preparations took place before the launch. The team (then Randolph, Christina, and Te) was strengthened with a CTO, the Frenchman Eric Meyer, and together they further developed the business plan. In July 1997, nine months before launch, Randolph met Mitch Lowe, who owned the video store chain Video Droid with 10 locations. Lowe was also building an underlying software infrastructure for video stores and was the President of the Video Software Dealers Association. Ultimately, Lowe was persuaded by Randolph to join the team in the fall of 1997 and would make a significant contribution to shaping Netflix's inventory in its early days, as well as spotting early movie hits, the so-called "blockbusters."

In the fall of 1997, eight months before the launch, Hastings instructed Randolph to bring in other investors. This wasn't for the capital itself, but it forced them to get additional perspectives on the business idea. By reducing his own $2 million commitment to $1.9 million, Hastings created the challenge of securing the remaining $100,000 from other investors.

One of the first candidates of Randolph and Hastings was Alexandre Balkanski, a major player in DVDs and video technology at the time. While Randolph noted that almost no one in Silicon Valley said "no" outright back then, Balkanski was blunt. According to Randolph, he said, "This is shit" halfway through the pitch. His criticism was remarkably prescient: DVDs, he argued, would only be an interim phase in the transition to downloading movies.

Balkanski questioned why he should invest in a company that might not provide any value in five years. It was a fair criticism, although the actual timeline for Netflix would prove to be much longer. This was because film studios were heavily leveraging the success of DVDs as a tool for end-user ownership, rather than a temporary service where ownership would lie with video rental stores as intermediaries, as was the case in the 1980s. The DVD era also allowed Netflix to build the necessary brand equity with customers for its eventual transition to streaming.

Despite the setback with Balkanski, Randolph didn't give up. He scheduled meetings with other potential investors, including Steve Kahn, Randolph's former boss at Borland International. Kahn, also one of the co-founders of Integrity QA and a friend and mentor to Randolph, would invest $25,000. He later admitted to Randolph that he thought at the time, "Well, that’s $25,000 I’ll never see again."

Randolph even secured an investment from his own mother to complete the funding goal.

In the following months, the team expanded, shipping envelopes were designed, and they began the monumental project of building a website and database from the ground up—a significant undertaking in 1997. The project, however, still had no name, which was a necessary step for setting up the business, bank accounts, and email addresses.

Kibble —> NetFlix

Kibble, Inc. was born on August 27, 1997, named after, of all things, dog food. The team soon realized the name wasn't a good fit, so they held a brainstorming session a few months after founding. They created a shortlist of names like TakeTwo and CinemaCenter, from which NetFlix ultimately emerged as the winner.

In the period leading up to the launch on April 14, 1998, (Netflix, 2022) the number of DVDs available from producers increased to around 800 titles. This allowed Netflix to offer a complete selection of all available titles at the time, something video rental stores weren't doing. Most of their customers at the time had a Video Home System (VHS) for videotapes, not a DVD player. At the same time, the question remained whether DVDs would ultimately catch on. "We weren't even sure if we'd identified the right problems," said Marc Randolph (2019).

On the morning of April 14, 1998, in Scotts Valley, NetFlix went live with an assortment of 926 titles and just two servers. Shortly after, a bell connected to the order system kept ringing with every new order, until the two servers eventually crashed. There was simply too much traffic. It was a clear sign, and they expanded their server count by eight that same day. On its first day, despite the crashes, Netflix received 137 orders (Marc Randolph, 2019).

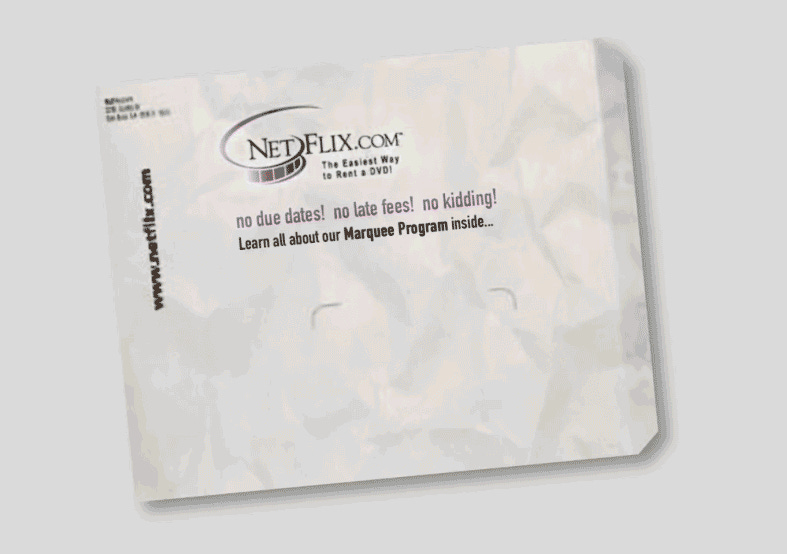

The process was simple. Customers would choose a DVD on the website, enter their address and credit card information, and a member of the Netflix team would then find the corresponding DVD with the order. Thereafter, the DVD was put into a sleeve, sealed with a promo sheet, and given a shipping label before it was ready to be sent.

Shipping would take two to three days, after which customers had seven days to watch their movie as many times as they wanted. Afterward, the customer could send the DVD back by mail; Netflix pre-paid for the return postage.

In the months that followed, Netflix continued to expand. They acquired more servers, collected data to improve customer service, and sealed a promotional deal with Toshiba and later with Sony. By June 1998, just two months after launching, they had generated $94,000 in revenue. Of this, a striking $93,000 came from DVD sales, and only a paltry $1,000 from DVD rentals. At the time, customers paid $25 to buy a DVD and $4 to rent one. While a sale earned six times as much as a rental, Marc Randolph (2019) noted, "...you can only sell a DVD one time. You can rent it hundreds of times."

This strong focus on DVD rentals was, of course, based on the large market for VHS rentals, with Blockbuster as the dominant player (in 1998, Blockbuster's revenue was $3.9 billion). With a future in sight where companies like Amazon and Walmart—and basically every physical store in America—could sell DVDs, they had to move quickly to improve their DVD rentals. This would become the path Netflix would pursue.

In the summer of 1998, after meeting with Jeff Bezos, founder and then-CEO of Amazon, to explore potential collaborations, Reed Hastings, who was still only peripherally involved with Netflix, realized the company's significant potential. According to Randolph (2019), Hastings said, "This business has real potential. I think we could make more on this than on the Pure Atria deal." After the meeting with Bezos, Randolph understood that they could never win the battle in DVD sales. A change in the company's strategy was needed.

In addition to the emerging competition, the business model was confusing for customers. Did Netflix sell or rent DVDs? The company was at a literal crossroads, with just 3% of its revenue coming from rentals. Ultimately, they decided not to sell their company to Bezos, who was interested. However, Netflix would later strike a deal with Amazon to direct customers who wanted to buy a DVD to Amazon, which in turn advertised Netflix on its homepage.

Despite securing an additional $250,000 in capital from Rick Schell, a former colleague of Marc Randolph's from Borland, Netflix's $2 million war chest was running low. Thanks to Hastings' strong reputation, Netflix was able to attract a new investor, Institutional Venture Partners (IVP), which provided $6 million in the summer of 1998. IVP would hold 4.6 million shares at the time of Netflix's planned IPO in April 2000 (SEC Info, 2000). However, it was all hands on deck for Netflix in the fall of 1998.

In mid-September 1998, Hastings had an unavoidable conversation with Randolph: he would be joining Netflix full-time as CEO.

“We have to move fast and almost flawlessly. The competition will be direct and strong.” [...] “So I think the best possible outcome would be if I joined the company full-time and we ran it together. Me as CEO, you as president.”

— Marc Randolph (2019)

This was a significant blow for Randolph. After all, it was his idea to start Netflix, his dream, and his company. "I sat there not speaking, just slowly nodding. That’s what happens when a piano falls out of the sky on your head," he recalled (2019).

The fact remained that Hastings and the other investors, holding the majority of the shares, had control over Netflix, which at the time employed 40 people. Ultimately, Randolph took the news well, stating, "...if the company was going to succeed, I needed to honestly confront my own limitations."

When your dream becomes a reality, it doesn’t just belong to you. It belongs to the people who helped you—your family, your friends, your coworkers. It belongs to the world.

— Marc Randolph (2019)

In the spring of 1999, Netflix moved to Los Gatos, where Randolph and Hastings continued to grow the company. Hastings took the lead on back-end programming and finance, while Randolph handled front-end matters such as marketing, analytics, PR, and public visibility. They brought in Barry McCarthy, an experienced finance director, as CFO, and Tom Dillon as head of operations, who would also help take Netflix to the next level (Variety, 1999). This spring marked the beginning of Netflix's next phase.

The deal Netflix had made with Amazon—to send DVD sales traffic to Amazon in exchange for Amazon sending rental traffic to Netflix—had failed. Netflix got the short end of the stick. Without the revenue from sales, the company had to pivot.

They came up with a new initiative that combined several ideas into a single plan: a $15.99 per month subscription for unlimited DVD rentals with no late fees, a one-month free trial, and four initial DVDs. This proved to be a masterstroke.

In February 2000, the à la carte rental service, which allowed customers to rent individual DVDs without a subscription, was discontinued. The company's sole focus shifted to the subscription service, which by then cost $19.99 per month. Netflix also launched Cinematch, an algorithm that made recommendations based on user reviews and other factors, such as DVD availability in Netfix’s inventory. That year, Netflix's revenue grew by 617% to $35.9 million, up from $5 million in 1999 (Netflix, 2002).

Despite this growth, the cash burn continued to accelerate. In the spring of 2000, with over 350 employees, Netflix needed to raise $50 million in a Series E funding round. In 2000, the company had a negative free cash flow of $47.7 million, roughly split between a negative operating cash flow and investments. The latter included $23.9 million for the “Acquisitions of DVD library” (Netflix, 2002).

Ted Sarandos, Netflix's current Co-CEO, was also hired around this time to lead content acquisition.

On the eve of the dot-com bubble burst, Netflix was making preparations for its IPO. However, due to the turmoil in the markets, the IPO did not happen that year. Thanks to the leadership of Reed Hastings—who had successfully taken Pure Software public and later merged it with Atria and later Rational—Netflix was able to survive.

In April 2000, Technology Crossover Ventures (TCV) invested $40 million in Netflix. By the time of the IPO, TCV would be the company’s largest shareholder.

Bernard Arnault, founder and CEO of the luxury conglomerate LVMH, also invested $30 million in Netflix through his investment vehicle, Europ@web (Variety, 1999; Wired, 1999; Sec Info, 2000). In 2000, Europ@web held a 14.3% stake in Netflix.

Netflix vs. Blockbuster

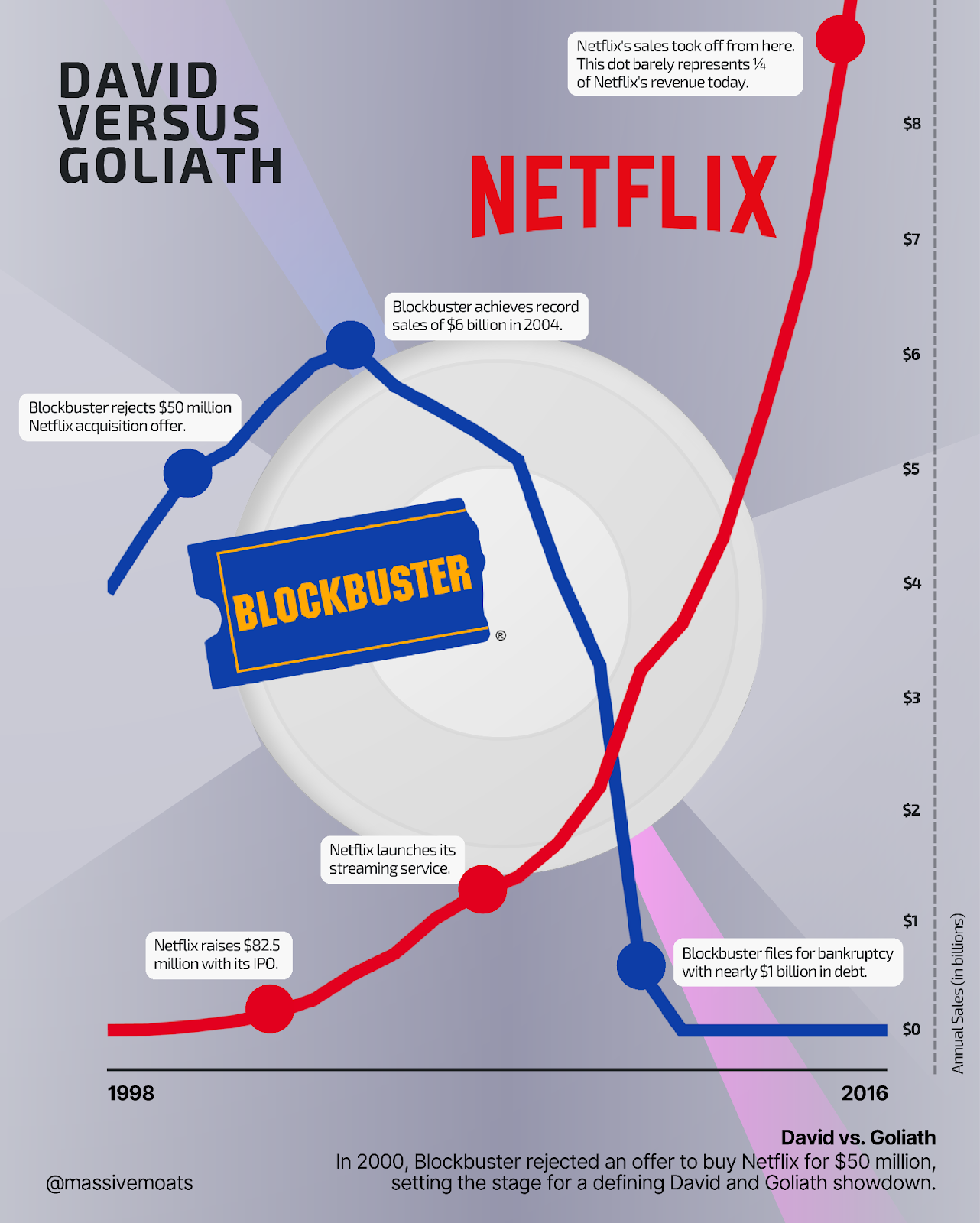

The real battle with Blockbuster began after the turn of the century. Until then, Netflix and Blockbuster were essentially playing different games: Netflix was focused on the internet and DVDs, while Blockbuster was concentrated on physical stores and VHS tapes, only later expanding into DVDs. In 1999, Blockbuster’s revenue was approximately $4.5 billion, while Netflix’s was a mere $5 million.

“They were Goliath. We were David.” (Randolph, 2019)

By the fall of 2000, Netflix was in urgent need of new capital. With institutional investors tightening their purse strings on technology companies, Netflix sought salvation elsewhere: from what would become its greatest competitor, Blockbuster.

The obvious strategic alternative for us was Blockbuster. Which is why, just a few weeks later, you’d have found me, Reed, and our CFO Barry McCarthy sitting at a giant conference table on the 37th floor of the Blockbuster headquarters in Dallas, getting ready to pitch Blockbuster.

— Marc Randolph (LinkedIn, 2023)

Netflix offered to sell itself to Blockbuster for $50 million. Blockbuster refused, setting the stage for a titanic struggle between the two companies. One was a titan with nearly 8,000 stores worldwide in 2001 (Blockbuster, 2005), and the other was a startup with a high cash burn.

Netflix was on its own and had to take decisive action to ensure its future survival.

Step 1 was to lay off 40% of the company's employees in September 2000. Netflix moved forward with only the best remaining staff, or "superstar players," as Randolph called them (2019).

Step 2 was to make the company's operations more efficient. To offer next-day delivery—a service strongly correlated with customer retention—across the entire United States, they opened around 60 Netflix Hubs. These small locations received DVDs and re-labeled them on the same day for shipment to the next subscriber. Since the vast majority of DVDs in circulation would be re-ordered within one or two days by another customer in the region, Netflix didn't have to build large storage warehouses. These hubs would later evolve into ultra-high-tech distribution centers capable of processing 1.8 million DVDs per day (Saylor Academy, 2012). These distribution centers were powered by advanced machines with high-precision scanners developed by the German company Dr. Schenk to detect physical imperfections (The Verge, 2023).

Step 3 was to raise additional capital to fuel growth. Netflix offered various promotions, including a one-month free trial subscription. This was well-received by American consumers but came with high upfront customer acquisition costs.

In 2001, the company raised $12.8 million through the issuance of subordinated notes payable and detachable warrants. The notes carried a 10% interest rate (Netflix, 2002).

The IPO

On May 23, 2002, more than two years later than initially planned, Netflix finally went public. The company raised $82.5 million by issuing 5.5 million shares at $15 per share (Netflix, 2002). Its 2002 annual report lists $88 million in "Proceeds from issuance of common stock," which indicates additional shares were sold (Netflix, 2002). Before the IPO, Reed Hastings held a 20.1% stake and Marc Randolph held 5.5%. The largest owners at the time of the IPO were venture capitalists, with Technology Crossover Ventures (TCV) being the biggest, holding 43.6% of the shares prior to the offering (Netflix Form S-1, 2002).

Randolph departed from Netflix in 2002, feeling the company had grown too large. His passion lay with startups and the unique challenges of solving the hundreds of problems that arise as these companies strive for growth. He sold his shares during the IPO because he did not want the majority of his wealth tied to a single company. Randolph continued to pursue his passion for startups by becoming an early-stage investor, mentor, and coach for young companies and their founders, a role he still maintains as of 2025 (Marc Randolph, 2025).

The Netflix vs. Blockbuster Saga Continues

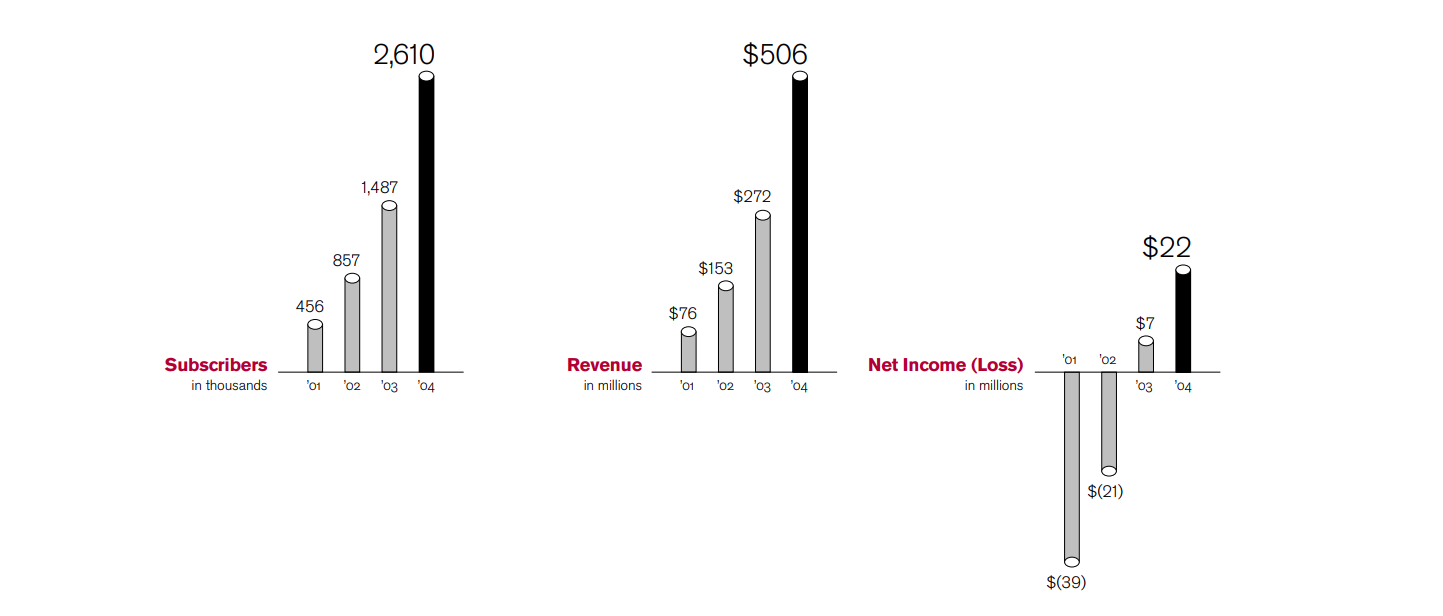

In 2004, far behind Netflix's technological advancements, Blockbuster finally introduced its own in-store subscription program and launched "Blockbuster Online." But it was too late. By then, Netflix had already amassed 2.6 million subscribers, a DVD library of 35,000 titles, and a distribution network capable of processing over 4 million DVDs per week.

To compete with Netflix, Blockbuster lowered the price of its online subscription to $14.99 in December 2004. Netflix responded by cutting its own rate, which it had initially raised from $19.95 to $21.99 that summer, down to $17.99—an 18% price reduction. In early 2005, Blockbuster also eliminated late fees for its in-store rentals (Netflix, 2004).

Netflix had anticipated a price war, hinting at further price cuts in its 2004 annual report: "...we may have to lower our prices and increase our marketing expenses in response to the aggressive competition from Blockbuster" (Netflix, 2004). In Q2 2005, Netflix launched a lower-priced subscription tier.

Despite the aggressive competition, Netflix members proved to be highly loyal. By the end of 2005, the company reported its lowest churn rate to date, at 4.0%. It also added 60% new subscribers, bringing its total to over 4 million. That year, Blockbuster's revenue declined for the first time. 2006 was another strong year for Netflix, with over 51% member growth, while Blockbuster’s revenue continued to fall.

Even with the launch of its "Total Access" program, Blockbuster couldn't reverse the trend. With the rise of activist investor Carl Icahn, Blockbuster's decline accelerated. The company was simply too slow to adopt streaming technology. Despite having the best market position, Blockbuster lost the battle because it failed to adapt to changing technological developments.

At its peak at the end of 2004, Blockbuster had approximately 84,300 employees worldwide, with about 58,500 in the U.S., and a total of 9,094 stores (company-operated + franchises), over 5,800 of which were in the U.S. (Blockbuster, 2004).

Streaming

In 2007, Netflix began its streaming service, and in 2012, it launched its first Netflix Original, Lilyhammer (IMDb: 7.9).

The transition to streaming would ultimately spell the end for DVDs. On September 29, 2023, the last DVDs were shipped, marking the conclusion of 25 years of DVD rentals and physical distribution for Netflix. Over that quarter-century, the company shipped over 5.2 billion DVDs to a cumulative 40 million subscribers (Netflix, 2023). In the final year of the service, DVD rentals accounted for just 0.2% of Netflix's total revenue ($82 million out of $33.7 billion).

The information in the preceding compilation, covering the period around Netflix's launch and the years that followed, has been distilled from the online sources mentioned and the following resources:

Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America's Eyeballs by Gina Keating (2013)

That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea by Marc Randolph (2019)

The two Netflix podcasts recorded by Ben Gilbert and David Rosenthal for Acquired:

Netflix (Part 1), Season 3, Episode 8 (Acquired, 2018)

Netflix (Part 2), Season 3, Episode 9 (Acquired, 2018)

The Wikipedia pages for Pure Software (2025), Netflix (2025), Marc Randolph (2025), and Reed Hastings (2025) are also recommended for further reading.

Chapter 2 | Strategy & Business Model

“We are here to entertain the world, one fan at a time.”

— Netflix (2025)

Strategy

At its core, Netflix's vision has remained unchanged since its early days in 1998: the company still strives to enrich its customers (now subscribers) with video content. However, the method by which Netflix achieves this in 2025 has certainly evolved.

We strive to continuously improve our members' experience by offering compelling content that delights them and attracts new members.

— Netflix (2024)

The company has successfully transitioned into the world of streaming and is now increasingly focused on producing its own original content. In doing so, Netflix isn't just positioning itself as a "content producer," but as the creator of new franchises—including games and merchandise—and, in turn, the owner of a content library built on its own intellectual property (IP).

By developing its own IP, Netflix is further committed to building a global entertainment business with its own creations. The focus remains on the customer experience and how to enhance it. To effectively meet customer needs and optimize its approach to the Total Addressable Market (TAM), the company offers consumers access to its video content through various subscription tiers.

Business Model

Netflix acquires, licenses*, and produces video content (i.e., films, series, and games) to offer to its members on a platform with unlimited access.

*) Licensing is the acquisition of rights from third parties to broadcast their content for a specific period in exchange for a fixed fee (Netflix, 2024).

Netflix's primary source of revenue is the monthly subscription fees paid by its members. Additionally, Netflix receives advertising revenue from companies.

Members, ARM & Geography

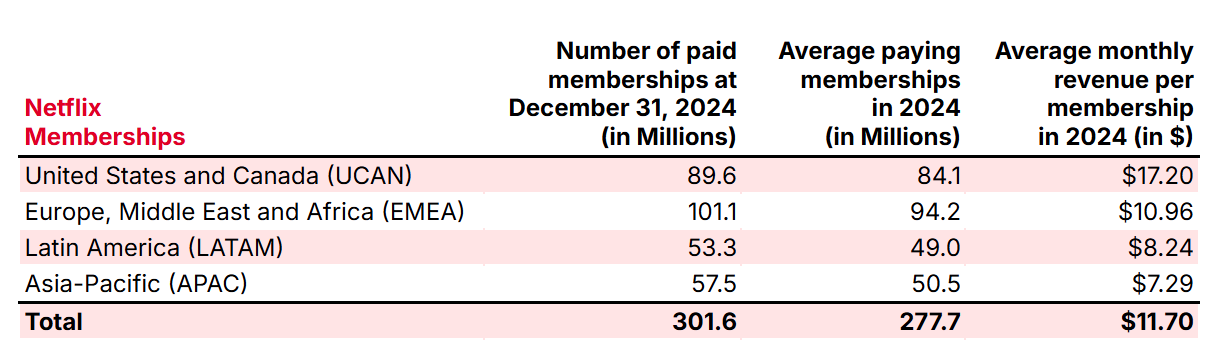

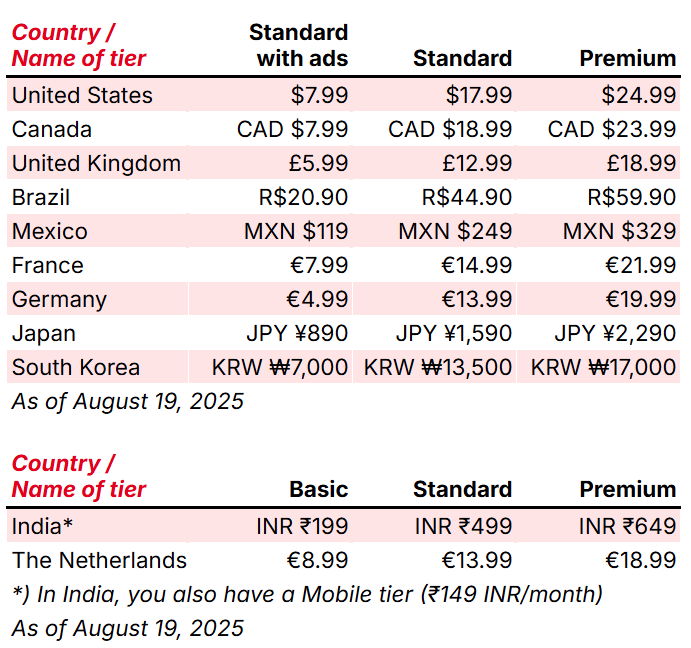

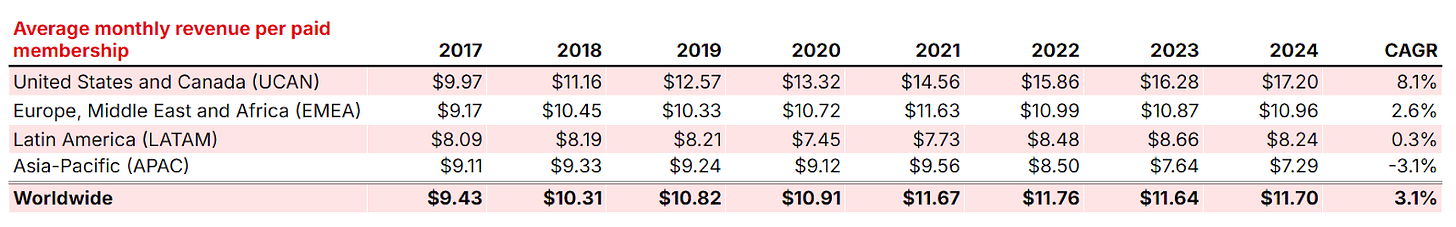

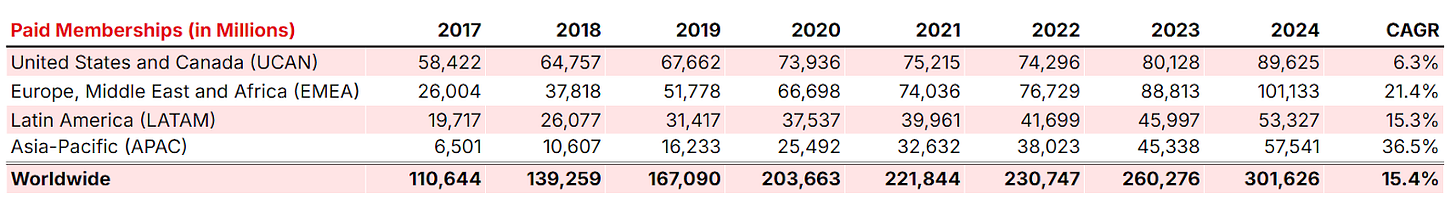

As of December 31, 2024, Netflix had 301.6 million paying subscribers worldwide. In 2024, these subscribers generated an average of $11.70 per month in U.S. dollars (this is a weighted average across its markets: United States & Canada, $17.20; Europe, Middle East and Africa, $10.96; Latin America, $8.24; and Asia-Pacific, $7.29) (Netflix, 2024).

With the publication of its 2024 annual results, Netflix provided its final update on its paid memberships and the average monthly revenue per member (ARM). This followed the company's April 2024 announcement that it would no longer report these metrics.

Below is an overview with Netflix's last available data (as of December 31, 2024).

In 2024, Netflix's average monthly revenue per paid membership (ARM) was $11.70. This figure was $11.64 in 2023 and $11.76 in 2022. The evolution of this ARM is detailed further in the Finance chapter.

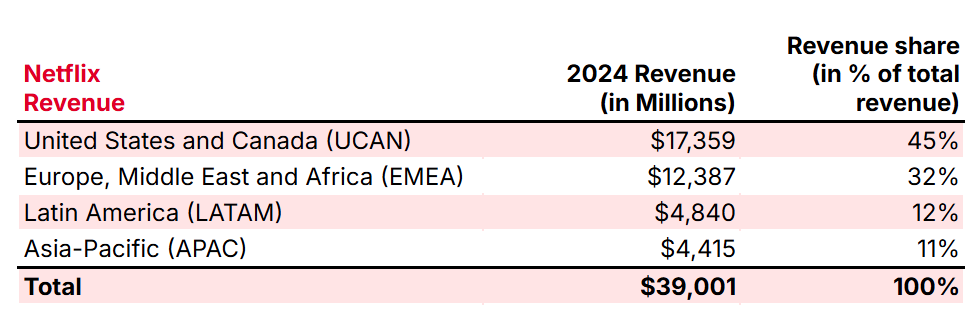

Netflix generates the majority of its revenue primarily from the United States and Canada (UCAN) and Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (EMEA). In 2024, these two regions combined accounted for 77% of the company's total revenue, as shown in the table below.

At the beginning of this year, the company reported that subscribers spend an average of 2 hours per day on the Netflix platform (2025). In July, the company announced that its members watched over 95 billion hours of content in the first half of 2025, which represents a 1% year-over-year increase (Netflix, 2025).

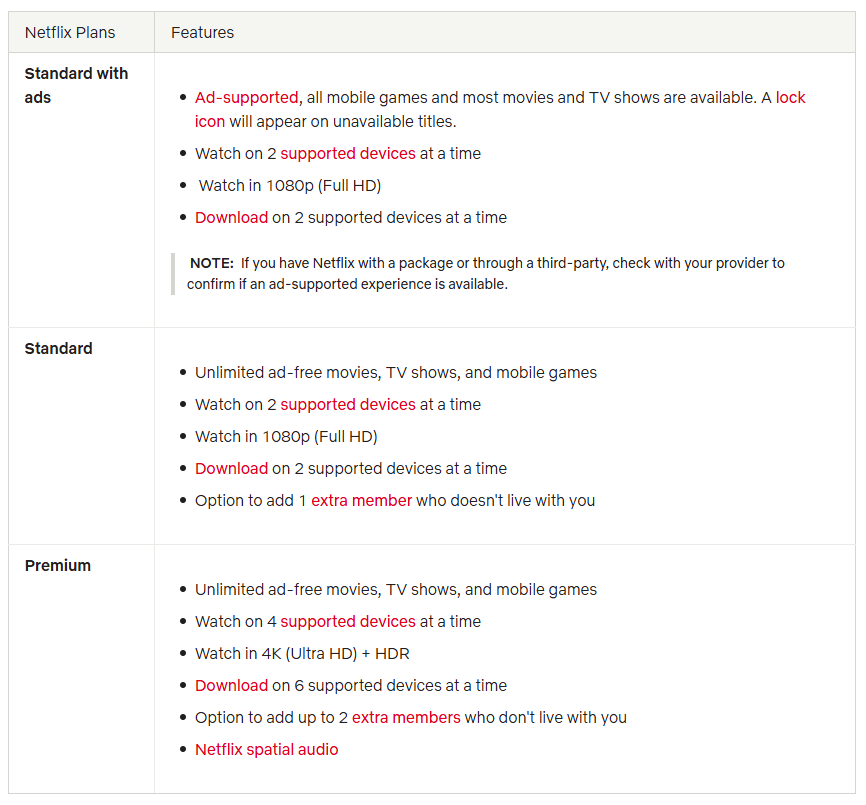

Subscription Plans

With a Netflix subscription, members gain access to the content on the company's platform. Consumers can choose from three main subscription tiers: Standard, Premium, and, as of late 2022, an ad-supported option.

Standard

The Standard-plan is the classic ad-free plan. It offers Full HD quality and allows for simultaneous viewing on two screens. Offline downloads are included.

Premium

The Premium-plan provides the highest video quality (4K Ultra HD) and allows for simultaneous viewing on up to four screens. It also includes offline downloads and is ad-free.

Standard with Ads

On November 3, 2022, Netflix launched its new "Basic with Ads" tier (Netflix, 2022). It started in its home market, the U.S., at a price of $6.99 per month. In January 2025, Netflix increased this rate to $7.99 per month (Forbes, 2025), a 14.3% increase. In the Eurozone, the price for this plan currently ranges from €4.99 to €7.99 per month (Netflix, 2025).

According to an internal survey (Netflix, 2024), 39% of Netflix's ad-supported subscribers do not have another ad-supported streaming service. This, according to Netflix, makes the platform an ideal proposition for attracting advertisers.

In the ad-supported subscription, a number of ads are shown per hour. Netflix aims to place these ads at natural breaks for the best user experience (Netflix, 2025). The company also integrates advertising during live events. According to Netflix's 2024 report, revenue from sources other than membership fees has not been a material component of total revenue in recent years (Netflix, 2024).

Subscription Tier Differences

The table below details the pricing for the three subscription tiers in 11 of Netflix's largest markets.

In India and the Netherlands, the cheapest tier is called "Basic." Currently, no advertisements are shown for these countries. In Netflix's other major markets, the name of the "Basic with Ads" plan has been changed to "Standard with ads."

As the table shows, Netflix carefully sets the prices and relative value of its different subscription tiers. In addition to the presence or absence of ads, there are other key differences between the plans. The table below explains these differences using the U.S. market as an example.

Broadly, the differences between Netflix Plans relate to:

The presence or absence of ads

The number of devices that can stream simultaneously

The number of devices for downloads

The maximum viewing resolution

Currently, there is no significant difference in content offered across the various subscription tiers. While Netflix notes that a small number of films and series are unavailable on ad-supported tiers due to licensing restrictions, subscribers on a "Standard with ads" plan generally have access to Netflix's full content library.

Will Netflix stick with these current differences, or will it also start to deliberately differentiate its content offering across subscription tiers in the future?

This question was posed during the Q2 2025 Earnings Call by Michael Morris of Guggenheim: "Is there a path to additional tiers of service based on types of content available? Or will Netflix always make all content available at the ad-free/ad-supported price points?" he asked (Netflix, 2025). Greg Peters, Netflix's Co-CEO, responded that he has learned to never say "never" and that Netflix remains open to evolving its consumer-facing model.

On May 14, 2025, Netflix (2025) announced that its ad-supported plan has over 94 million monthly active users and attracts more 18- to 34-year-olds than any other U.S. broadcast or cable network. Netflix also shared that subscribers of the ad-supported membership in the U.S. are highly engaged, spending an average of 41 hours per month on the platform.

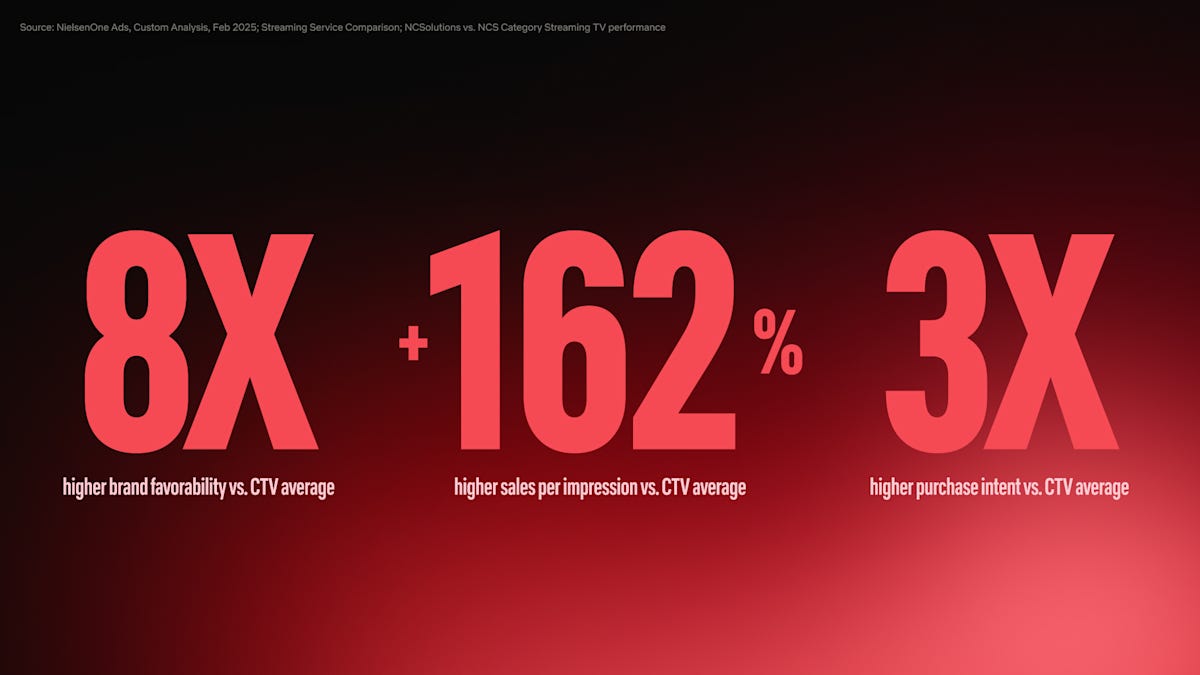

Netflix has also developed its own Ads Suite, offering more than 100 interests across 17 categories that companies can use to effectively reach Netflix subscribers with their ads (Netflix, 2025).

Netflix Originals

A key component of Netflix's business model has become its own content production, known as Netflix Originals. In addition to buying and licensing content, the company produces its own material, also in collaboration with partners. In the latter case, Netflix is the exclusive distributor and brands the content as a Netflix series. As of December 31, 2024, Netflix's balance sheet showed $20 billion in self-produced content, which represents over 60% of the company's total capitalized content assets. More on this can be found in the Finance chapter.

Netflix Originals content has proven popular with viewers. On IMDb, where users can rate films and series, the following titles have received very high scores: Our Planet II (9.2), Arcane (9.0), Dark (8.7), Black Mirror (8.7), Narcos (8.7), House of Cards (8.6), The Crown (8.6), Stranger Things (8.6), The Last Kingdom (8.5), The Queen’s Gambit (8.5), Ozark (8.4), Adolescence (8.2), La Casa de Papel (8.2), and Squid Game (8.0) (scores from IMDb, 2025).

Older titles also remain popular. In July 2025, Netflix reported that nearly half of the viewing hours for Netflix Originals came from titles that were launched in 2023 or earlier (Netflix, 2025). This, in my opinion, is a growing strength for Netflix: the ability to build its intellectual property (IP) with a broad assortment of exclusive content.

On December 28, 2022, Netflix announced its intention to build a studio campus for nearly $1 billion in New Jersey, the birthplace of film. The opening is scheduled for 2028 (Netflix, 2025).

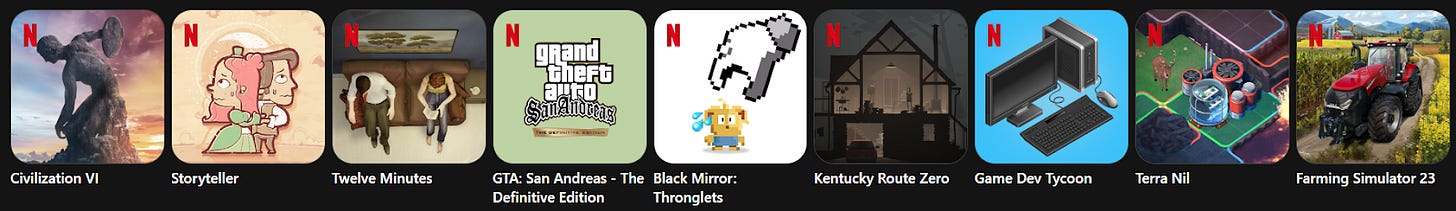

Games

In addition to films, series, and live events, Netflix is also focusing on games. In July 2024, Alain Tascan was appointed head of the company's gaming division (Netflix, 2024). He brings experience as the Executive VP of Game Development at Epic Games, where he oversaw the production of titles like Fortnite and Rocket League.

The current scale of Netflix's gaming operation is still small. During the Q2 2025 Earnings Call, Greg Peters, co-CEO of Netflix, stated: “We've seen those positive effects, albeit in a small way relative to the size of our overall business when it comes to members playing games on the service. We already have those positive proof points. And we're going to ramp our investment in this area, which is currently quite small compared to our overall content investment.”

Netflix Houses

With Netflix Houses, the company plans to enter the physical entertainment space, primarily as a showcase for its brand and franchises. At these locations, visitors will be able to immerse themselves in the world of their favorite Netflix franchises, such as Squid Game, where they can play the famous games from the series.

The first two locations are scheduled to open at the end of this year in Philadelphia and Dallas. A third location is planned for Las Vegas in 2027 (Netflix, 2025).

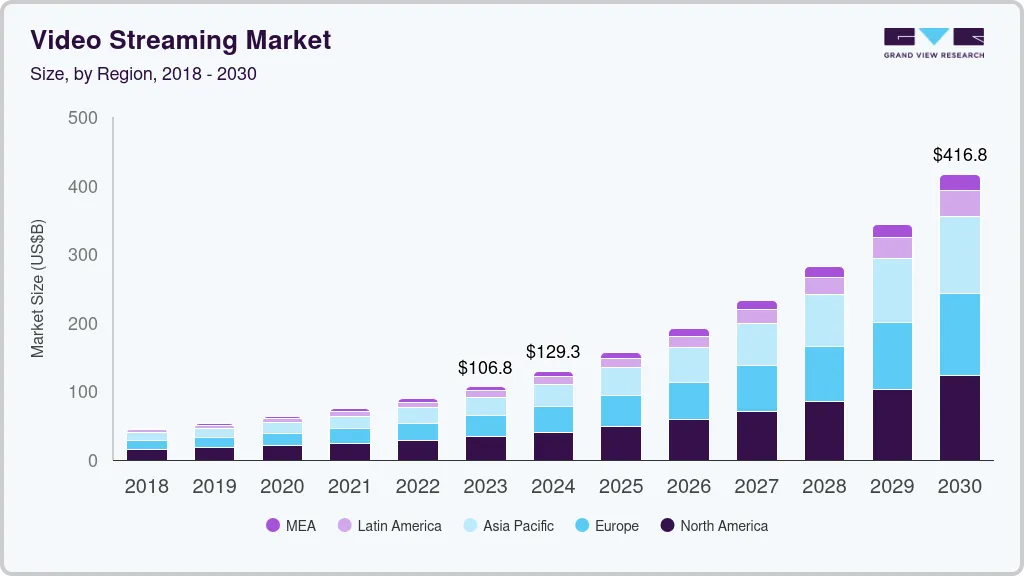

Chapter 3 | Market & Competition

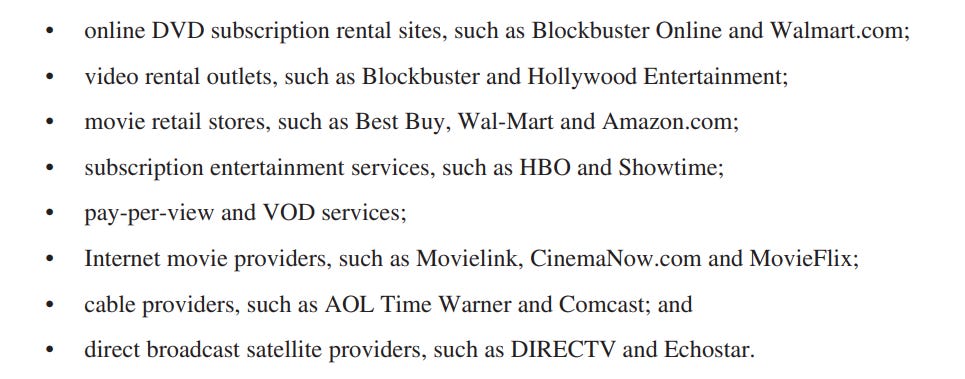

Where consumers once primarily listened to the radio or rented a VHS from Blockbuster, the market for consumer leisure has changed significantly over the past few decades. Whether it's time spent on televisions, smartphones, computers, or outdoor activities, Netflix is essentially competing with the entire consumer leisure market. This variety of competition is not foreign to Netflix; even in its early days, it managed to contend with many vested parties:

In the market of direct competition, Netflix nowadays refers to companies with a similar business model (entertainment video providers, streaming entertainment providers), but also to other video providers (such as linear television) and to user-generated content and social media (Netflix, 2024).

Netflix aims to differentiate itself by focusing on a combination of technology and content offerings.

While consumers may maintain simultaneous relationships with multiple entertainment sources, we strive for consumers to choose us in their moments of free time. We have often referred to this choice as our objective of "winning moments of truth." In attempting to win these moments of truth with our members, we seek to continually improve our service, including both our technology and our content offerings.

— Netflix (2024)

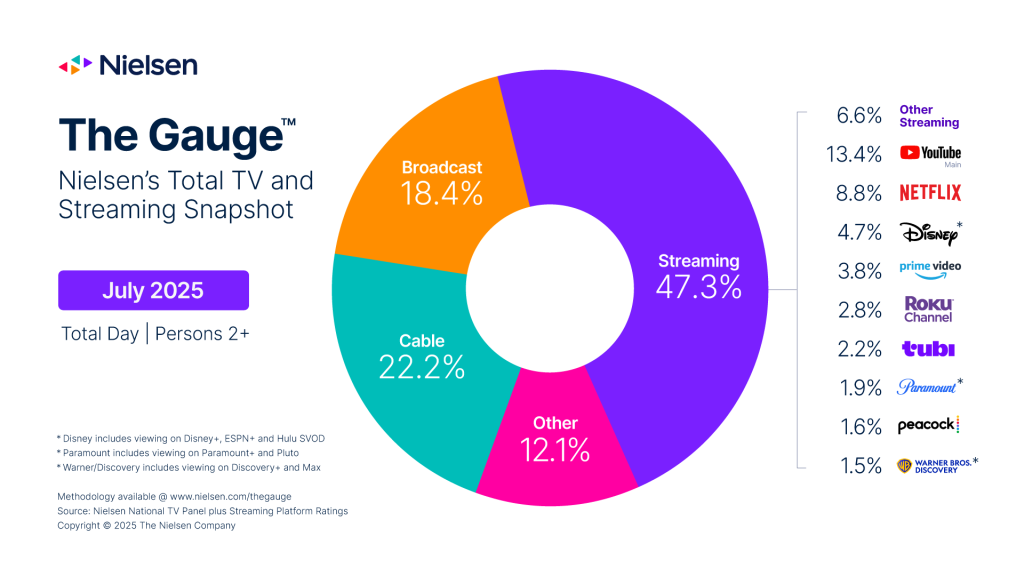

TV Time (Cable, Broadcast + Streaming)

The primary market Netflix competes in is consumer screen time spent on TVs and similar devices. Traditionally, this was dominated by cable networks and broadcast TV providers. In recent years, this market has shifted toward streaming, according to Nielsen, which tracks TV viewing in the United States.

Last May, streaming reached a historic high, surpassing the combined share of broadcast and cable for the first time (Nielsen, 2025). When Nielsen first began publishing its monthly The Gauge report in May 2021, Cable held a 39% market share and Broadcast had 25%. At that time, streaming's share was 26% (Nielsen, 2021).

Over the past four years, streaming's share has grown to 47.3%. Within the streaming segment, YouTube appears to become a clear winner, with its market share increasing from 6% in May 2021 to 13.4% as of July 2025 (Nielsen, 2025). According to Nielsen, Netflix's share has grown from approximately 6% in May 2021 to 8.8% in July 2025.

The trend is clear: Streaming is gaining an increasingly larger share of consumer TV viewing time. Below is an overview of the biggest players in the streaming world.

YouTube

With YouTube, Alphabet (formerly Google) operates a platform where consumers, businesses, and professional content creators can upload video material that is then freely available for other users to watch. The platform is free to use, and its business model is centered on advertising. A portion of YouTube's ad revenue goes to the video creators.

It's also possible to watch ad-free with a subscription (YouTube Premium). This subscription also offers the ability to download videos for offline playback, as well as continued playback when you lock your screen or switch to another app on your smartphone. According to the company, there are more than 125 million YouTube Premium members (YouTube, (2025).

The Walt Disney Company

As of June 28, 2025, Disney+ had 127.8 million paying subscribers. On the same date, Hulu, which is also under the Walt Disney umbrella, had 55.5 million members. For the quarter ending on that date, Disney earned an average of $8.09 per paying subscriber in the U.S. and Canada, and $7.67 internationally (The Walt Disney Company, 2025).

HBO Max (Warner Bros. Discovery)

As of June 30, 2025, the number of paying subscribers for discovery+ and (HBO) Max was 125.7 million. The ARPU (Average Revenue Per User) was $11.16 in the U.S. and Canada and $3.85 in its international markets (Warner Bros. Discovery, 2025).

Amazon Prime Video

Amazon's Prime subscription extends beyond just video content on Prime Video. Prime subscribers also receive benefits like free and fast shipping on Amazon orders, exclusive deals, Prime Gaming, and Amazon Photos (Amazon, 2025).

In 2021, Amazon acquired the film studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) for $8.45 billion (Amazon, 2021). This acquisition gave Amazon access to a catalog of over 4,000 films and 17,000 TV episodes (Amazon, 2021), including series like The Handmaid’s Tale (8.3/10, IMDb), Fargo (8.8/10, IMDb), and Vikings (8.5/10, IMDb). Following the acquisition, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was renamed Amazon MGM Studios.

Netflix

Netflix's most recent subscriber figures date from December 31, 2024, at 301.6 million. In 2024, these subscribers provided an average ARM of $11.70. This makes Netflix, by far, the largest streamer among its direct competitors in terms of paying subscribers.

More on Netflix's financials can be found in the Finance chapter.

In the Risks & Opportunities chapter, I will provide my perspective on the aforementioned competitors and potential developments surrounding artificial intelligence and the risks it poses to Netflix.

Chapter 4 | Financials

In this chapter, we will delve into Netflix's financials using its balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows. We will also examine the company's capital allocation. We begin with a look at the company's financial health and its degree of value creation for shareholders.

4.1 | Financial Health & Value Creation

I assess Netflix to be a financially healthy company. As of June 30, 2025, Netflix had a cash, cash equivalents, and short-term investments balance of $8.4 billion versus a debt position of $14.4 billion (both unaudited). This brings Netflix's total net debt position to approximately $6 billion. For comparison, this net debt position was $9.7 billion as of December 31, 2019.

In my view, a controlled amount of long-term debt is a sign of good management, provided, of course, that the return generated on this capital is higher than the cost of that debt.

Netflix's long-term debt consists of outstanding bonds (Senior Notes) maturing from November 2026 to August 2054, with a weighted average interest rate of approximately 4.8%. This is the input for the debt component in Netflix's weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

In 2024, Netflix achieved a return on invested capital (ROIC) of approximately 24% (2023: approx. 17%), which is exclusive of a correction for its excess cash and short-term investments. If we were to correct for this excess cash, cash equivalents, and short-term investments, the percentage would be around 30% (2023: approx. 21%).

From this, we can conclude that the company’s ROIC improved last year compared to 2023. This indicates that Netflix's return on incremental invested capital (ROIIC) is also very positive. In other words, the change in Netflix’s NOPAT (Net Operating Profit After Tax) was greater than the increase in its invested capital.

Therefore, we can conclude that Netflix is creating value for its shareholders on its raised debt—which has a weighted average cost of approximately 4.8%—with a delta of over 20 percentage points. In theory, Netflix could quickly pay down its $6 billion net debt position: the company's free cash flow (FCF) for 2024 was $6.9 billion (2023: $6.9 billion). In conclusion, I rate Netflix's financial position as healthy.

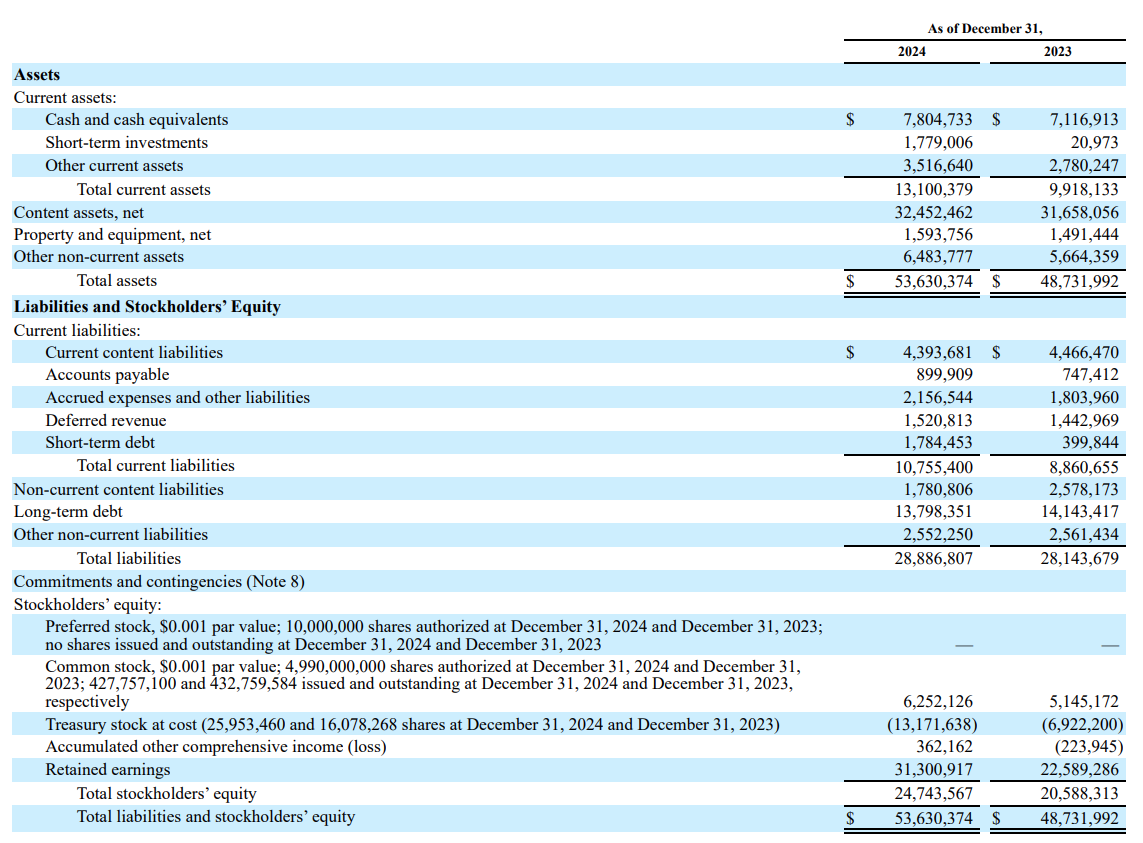

4.2 | Balance Sheet

The balance sheet of Netflix as of December 31, 2024, is shown below.

Assets

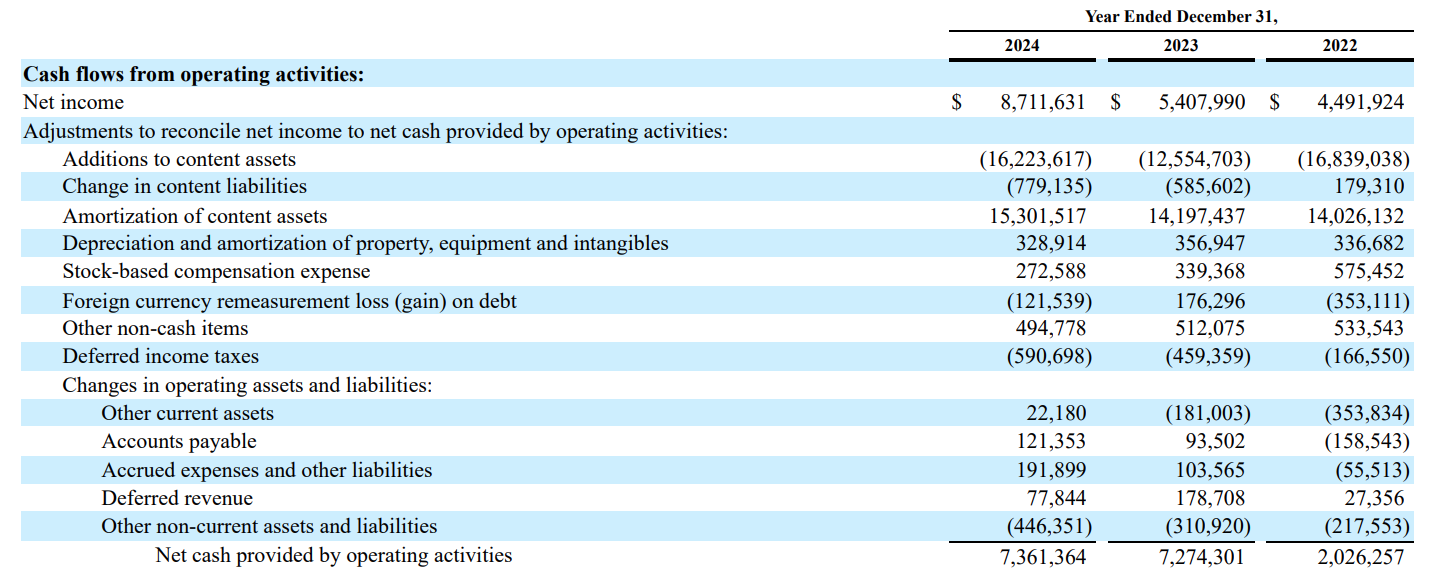

In addition to the C&CE and short-term investments already discussed ($8.4 billion as of June 30, 2025; $9.6 billion as of December 31, 2024), Netflix’s content library is a significant component of its balance sheet.

These content assets are intangible assets. Netflix capitalizes the costs to acquire, license, or produce this content on its balance sheet and then amortizes them over a period of time.

As of June 30, 2025, the company had $32.1 billion in Content assets, net. This amount is roughly consistent with the figure from the end of 2024 ($32.5 billion). The 2024 statement of cash flows shows that $16.2 billion was capitalized that year (Additions to content assets), while $15.3 billion was amortized (Amortization of content assets).

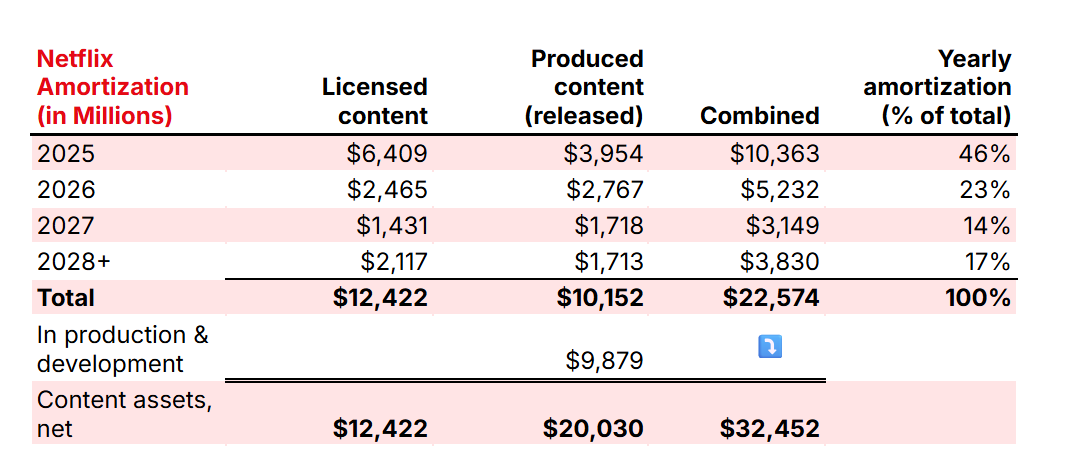

Netflix's 2024 annual report provides more detail on the composition of these content assets. The $32.5 billion balance can be broken down as follows (balances as of December 31, 2024) (Netflix, 2024):

$12.4 billion in Licensed content, net;

$20.0 billion in Produced content, net.

Licensed content, net represents the net balance of capitalized content licensed from third parties. Produced content, net refers to the net balance of content produced by Netflix or by partners on behalf of the company.

Produced content, net can be further segmented into:

$10.2 billion for content that has already been released on the platform (Released, less amortization)

$9.3 billion for content still in production (In production)

$0.6 billion for content in the development and pre-production stages (In development and pre-production)

Netflix amortizes its content assets using an accelerated method, which means that the capitalized balance of a content asset on the balance sheet will be higher in the first year than in the final year of amortization. Netflix uses this method because it expects more viewing activity during the initial release period. The company notes that films are amortized faster than series (Netflix, 2024).

On average, more than 90% of licensed or produced content is amortized within four years of its first month of availability on Netflix’s platform (2024). The amortization schedule's progression depends on historical and expected viewing patterns. After four years, the majority of Netflix's self-produced content will have disappeared from the balance sheet, even though it remains available to subscribers. It may be gone from an accounting standpoint, but it is still part of the IP library.

This accelerated amortization method is also visible in Netflix's expected amortization schedules. Based on the comments in the most recent annual report (Netflix, 2024), I have constructed the table below.

As you can see in the table, Netflix expected to amortize 46% of the content asset balance on its balance sheet as of December 31, 2024, in 2025. This shows Netflix's accelerated amortization method, with 23% expected amortization in 2026 and 14% in 2027. The remaining portion is expected to be amortized in 2028 and beyond.

Netflix's own productions make up over 60% of its capitalized content assets, with licensed content accounting for 40%.

The chart below shows the annual content investment costs.

Investments Netflix makes in content production must be made upfront (creating pressure on its FCF), which will later contribute to Netflix's cost of revenue in the form of amortization. Content investments are necessary to ensure that compelling content is available for its members in the future. As Netflix states: "We expect to continue to significantly invest in global content, particularly in original content, which will impact our liquidity" (Netflix, 2024).

Additionally, Netflix's balance sheet as of December 31, 2024, includes $1.6 billion in Property and equipment, net. This balance primarily relates to real estate and leasehold improvements. Furthermore, a gross amount of $446 million is attributed to Information technology. This figure is relatively low for a global company that operates on a technology-driven infrastructure.

This low technological footprint on its own balance sheet is a result of the company building its digital infrastructure on Amazon Web Services (AWS) servers. Netflix closed its last in-house data center in 2016, completing a migration to the cloud that began in 2008 (Netflix, 2016). Netflix uses AWS for a significant portion of its computing. This is also highlighted as a risk in the Risk Factors section in its annual report:

Currently, we run the vast majority of our computing on AWS. Given this, along with the fact that we cannot easily switch our AWS operations to another cloud provider, any commercial disputes related to, disruption of or interference with our use of AWS would impact our operations and our business would be adversely impacted.

— Netflix (2024)

Netflix also addresses the inherent tension with Amazon's retail arm, which it essentially competes with:

While the retail side of Amazon competes with us, we do not believe that Amazon will use the AWS operation in such a manner as to gain competitive advantage against our service, although if it were to do so it could harm our business.

— Netflix (2024)

My perspective on these risks is detailed in the Risks & Opportunities chapter.

In addition to AWS, Netflix's Open Connect also plays a crucial role in delivering video content to its subscribers (Netflix, 2019).

As of June 30, 2025, the total balance of Content assets, net was $32.1 billion, accounting for approximately 60% of Netflix's total assets. Together with C&CE and short-term investments, this represents 76% of Netflix's total assets.

Liabilities & Stockholders’ Equity

The liabilities side of Netflix's balance sheet is also straightforward. It includes $14.5 billion in long-term debt and $25 billion in shareholder's equity, which together make up 74% of Netflix's total liabilities and stockholders’ equity (Netflix, 2025).

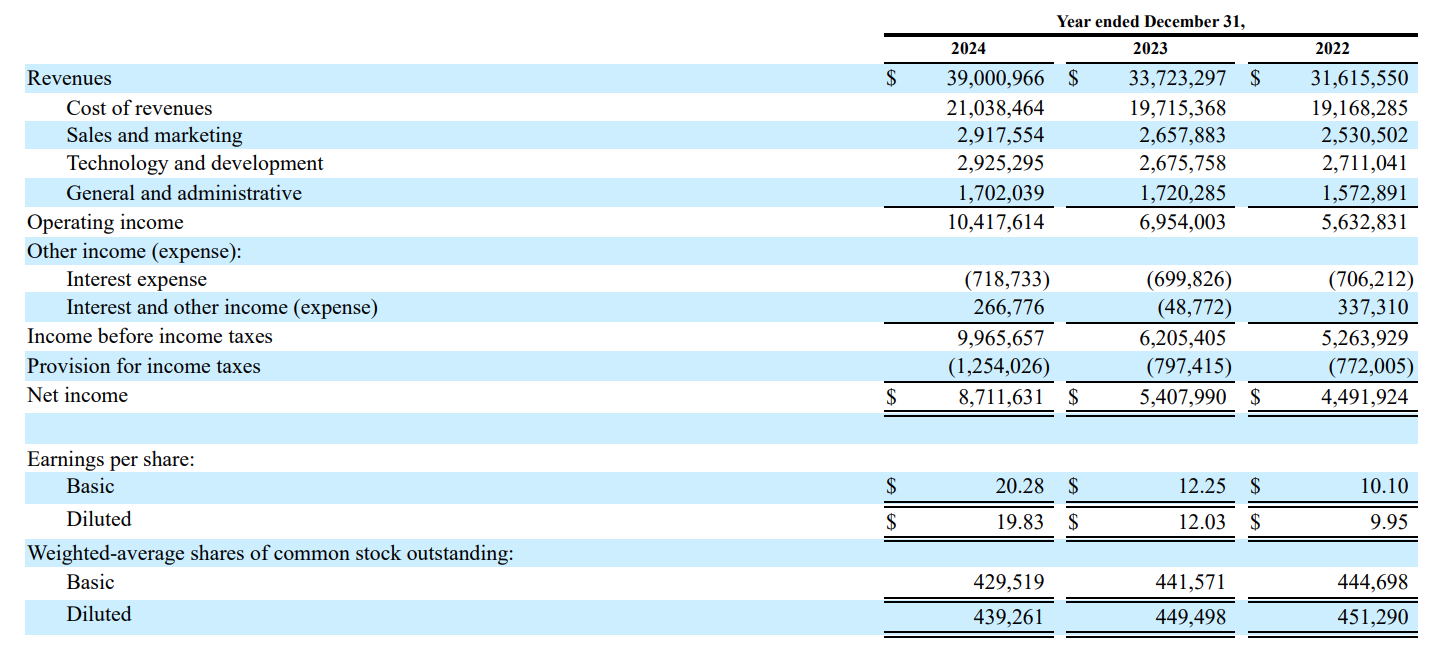

4.3 | Income Statement

Below is Netflix's income statement for the last three fiscal years. The following section will discuss the elements of this income statement.

Revenue

Starting with DVD sales and rentals, then moving to DVD subscriptions, and now in 2025, fully focused on streaming services, Netflix's revenue has a rich history.

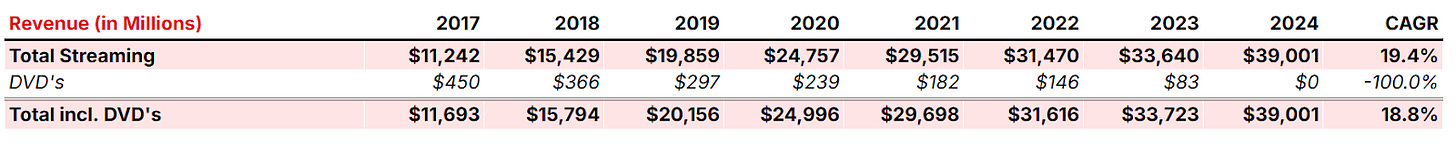

Up to fiscal year 2023, Netflix still reported revenue from DVDs, as its DVD.com service was active until September 29, 2023. On that date, Netflix shipped its final DVD (Netflix, 2023). Given the transition to streaming, this was a logical step for Netflix. The decline in demand for physical DVDs was evident in the preceding years. The table below provides an overview of revenue from streaming versus DVDs since 2017.

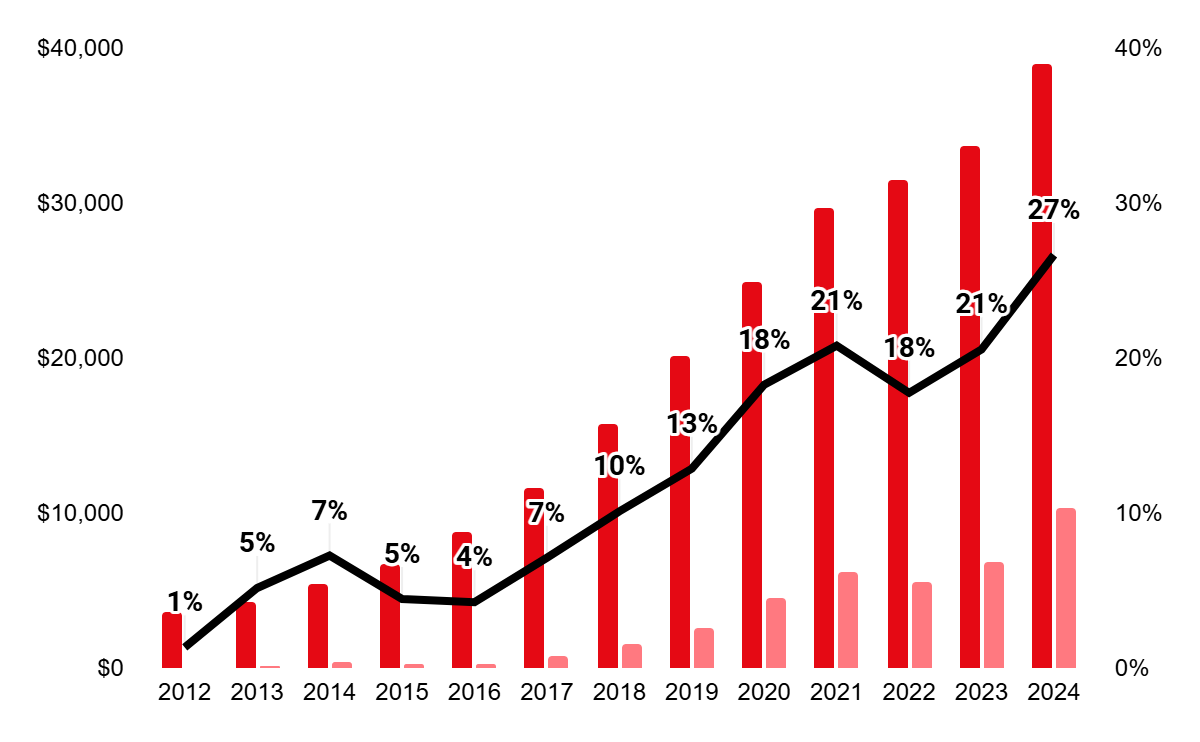

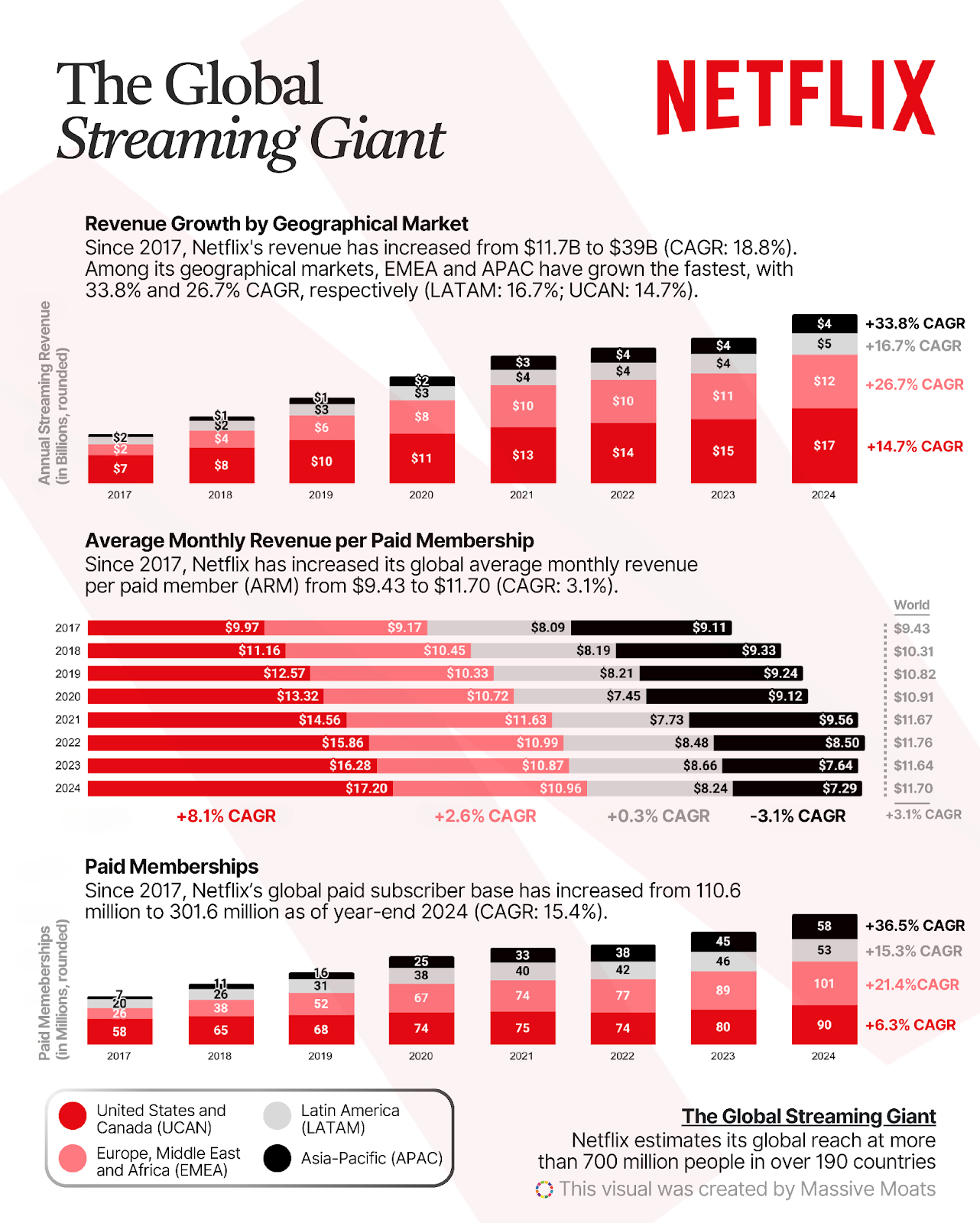

Since 2017, Netflix's total revenue has grown at an 18.8% CAGR, from $11.7 billion to $39 billion. Excluding DVDs, streaming revenue grew at a 19.4% CAGR.

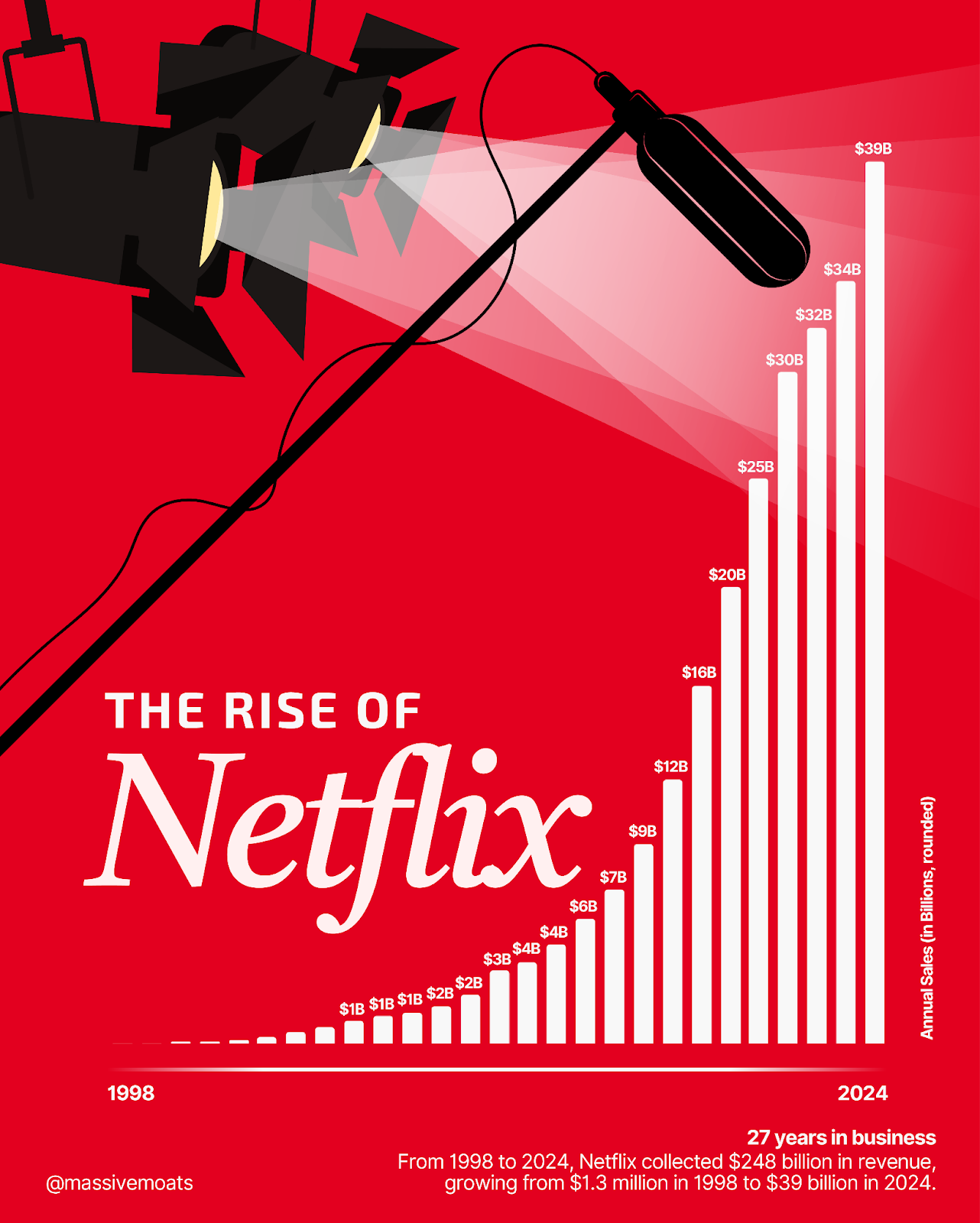

The chart below shows Netflix's revenue growth since its launch in 1998. Over the past 27 years, the company has generated a cumulative revenue of $248 billion.

Geographical Market Breakdown

Netflix distinguishes between the following four geographical markets:

United States and Canada (UCAN)

Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA)

Latin America (LATAM)

Asia-Pacific (APAC)

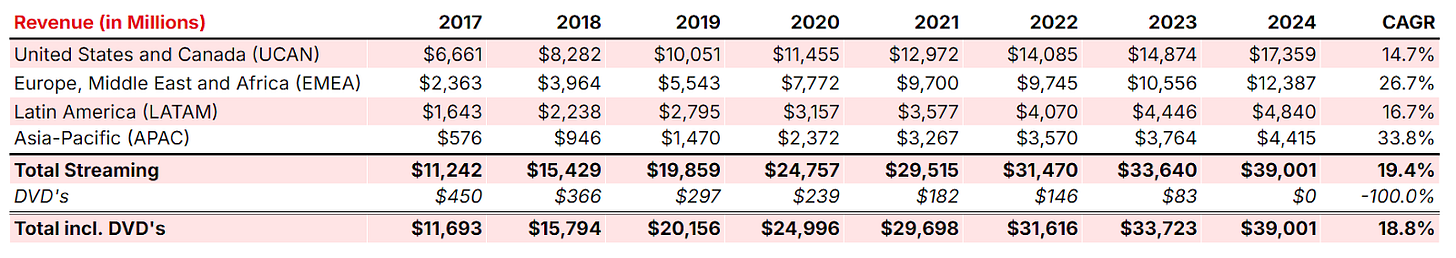

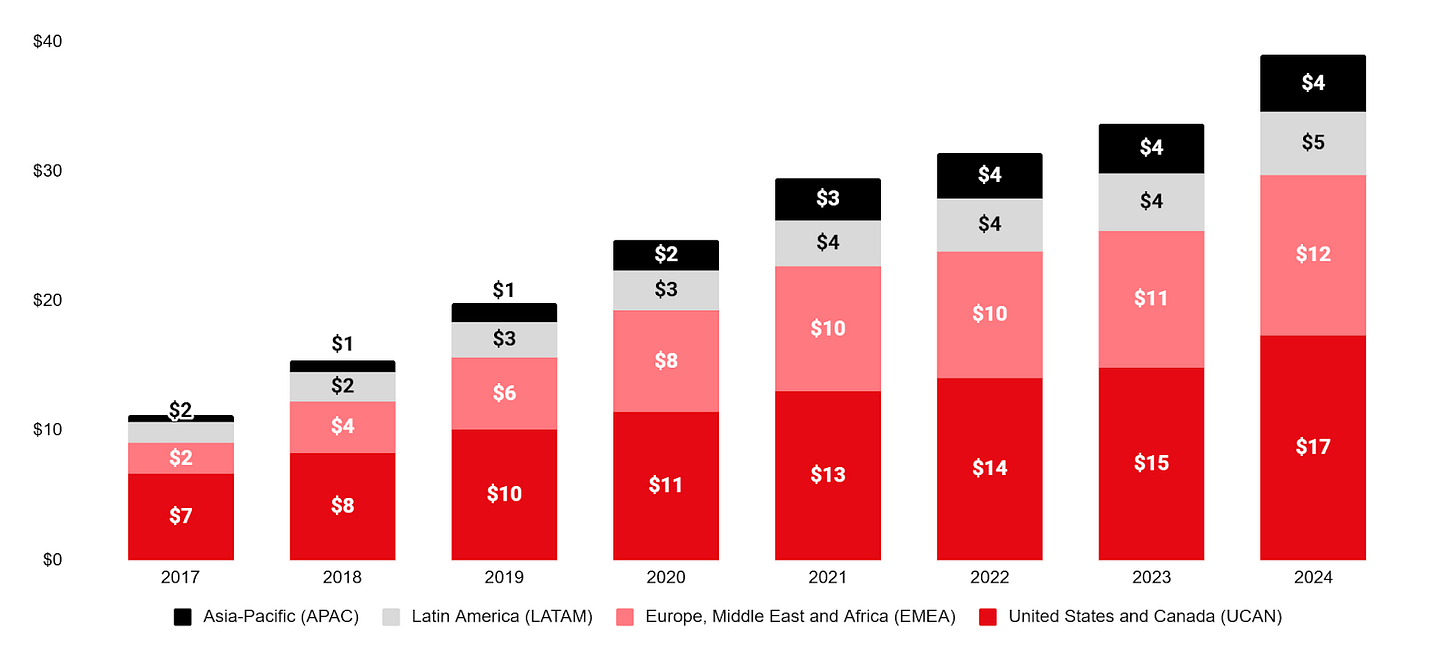

The table and chart below show Netflix's revenue growth by market since 2017.

Since 2017, Netflix has grown its revenue at an 18.8% CAGR, from $11.7 billion that year to $39 billion in 2024. Within its markets, APAC and EMEA showed the strongest growth, with a CAGR of 33.8% and 26.7%, respectively. In LATAM and UCAN, the annual sales growth was 16.7% and 14.7% CAGR, respectively. In absolute terms, UCAN is the largest market with $17 billion in 2024 revenue, followed by EMEA with $12 billion.

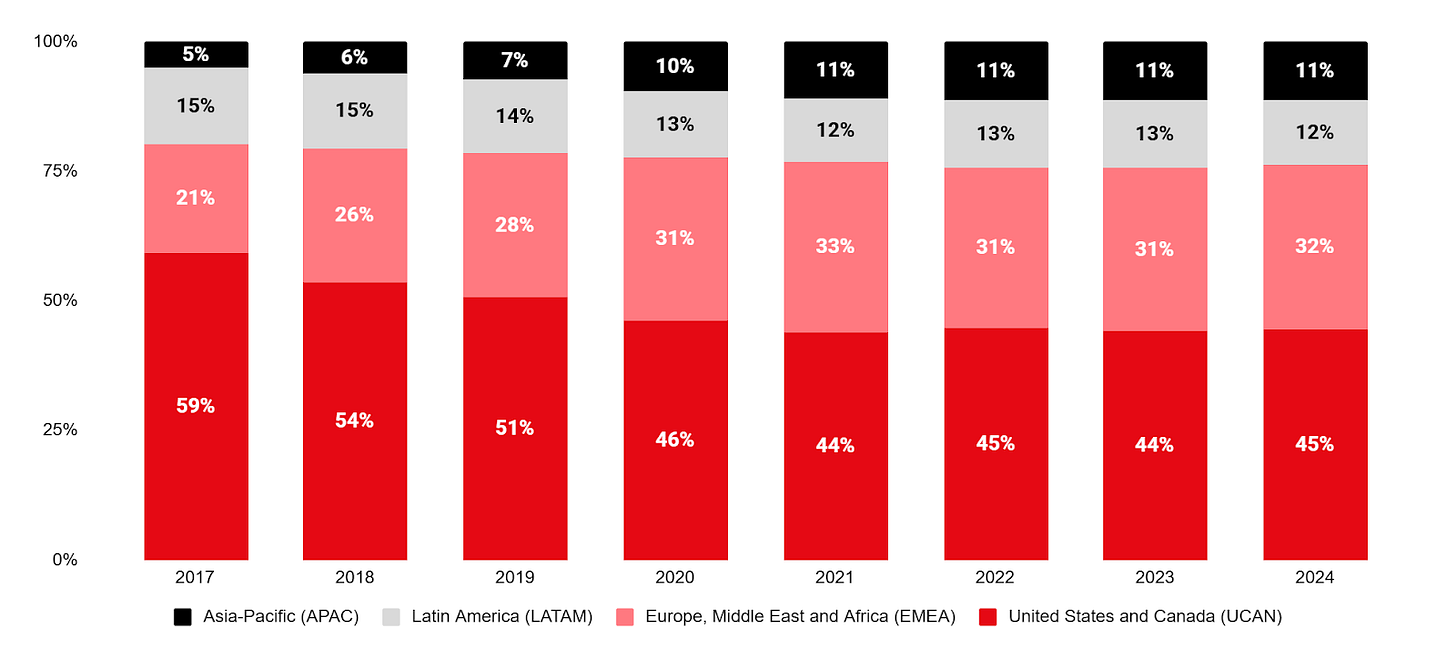

The chart below shows the development in the revenue weighting of each market as a percentage of the total.

The chart shows that UCAN's share decreased from approximately 59% in 2017 to roughly 45% in 2024. This 14-percentage-point decline was caused by the faster growth of EMEA, which increased its share by 11 percentage points to 32%. With its above-average growth, APAC also increased in size. LATAM's share shrank slightly.

Netflix's revenue growth is driven by two factors: price and volume. The following section explains these two elements.

Average Revenue Per Member

Let's start with the price component. A good metric for this is the average revenue Netflix receives per paying subscriber, which the company expresses monthly as Average Monthly Revenue per Paying Membership (ARM).

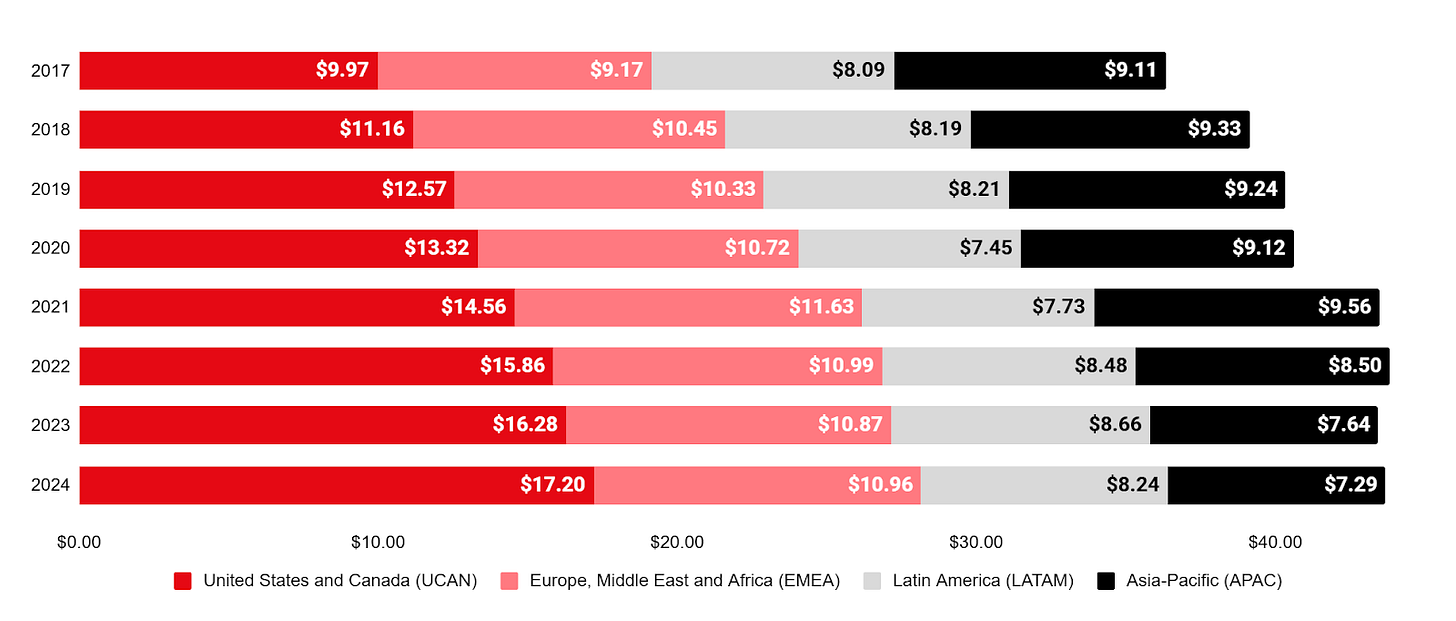

Globally, this ARM grew by an average of 3.1% CAGR, from $9.43 in 2017 to $11.70 in 2024. The diagram below shows the development of Netflix's ARM per market over the past few years.

Over the period from 2017 to 2024, UCAN showed the largest increase in ARM with an 8.1% CAGR, rising from $9.97 to $17.20. For EMEA, this growth was more moderate at 2.6%, from $9.17 to $10.96. In LATAM, the average amount Netflix receives in dollars per paying subscriber has remained largely stable, with ARM rising from $8.09 to $8.24 (a 0.3% CAGR). For APAC, a decline is even visible in dollars, from $9.11 in 2017 to $7.29 in 2024 (a -3.1% CAGR).

With a 3.1% CAGR in price growth on a total revenue growth for Netflix of 18.8% (19.4% for streaming), this inherently means that the majority of this revenue growth was driven by the increase in Netflix's subscriber base.

Subscriber Growth

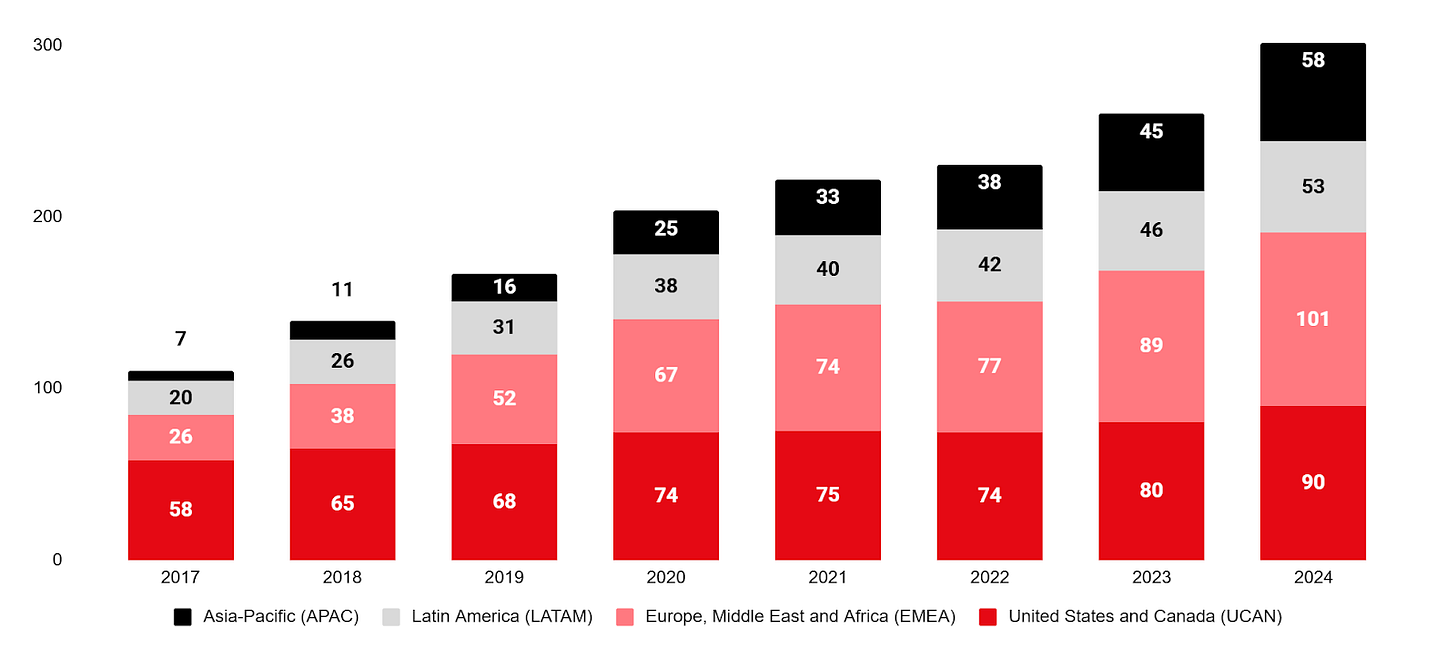

Since 2017, the number of Netflix paying members has grown at a 15.4% CAGR, from 110.6 million at the end of 2017 to 301.6 million at the end of 2024.

The chart below shows the development of the subscriber count per market.

The strongest growth in the number of paid members occurred in APAC, where the subscriber count increased from 7 million to 58 million (a 36.5% CAGR). In EMEA, the growth was a 21.4% CAGR, from 26 million to 101 million subscribers. This has made EMEA Netflix's largest market in terms of members, surpassing UCAN (from 58 million at the end of 2017 to 90 million at the end of 2024). The smallest market for Netflix is LATAM, which grew from 20 million to 53 million over the past seven years.

Below is an overview of the price and volume components per region.

Cost of Revenues

Netflix's Cost of Revenues primarily consists of the amortization of its content assets, as detailed in section 4.2 of this deep dive, Netflix’s Balance Sheet.

A clear decline is visible when we look at the percentage of these costs relative to Netflix's revenue. While this percentage was 62% in 2019 ($12.4 billion out of $20.2 billion), it decreased to 54% for fiscal year 2024 ($21.0 billion out of $39.0 billion). Despite the absolute increase from $12.4 billion to $21.0 billion, the percentage decreased because Netflix's revenue grew at a faster rate.

Since the Cost of Revenues is mainly comprised of amortization on content assets, we can infer Netflix's economies of scale: as its subscriber base grows, Netflix receives more capital to invest in producing and licensing content.

Increasing economies of scale work as follows: when companies expand their product or service offerings, it attracts new customers, who in turn contribute to the resources available for the company's future offerings. In Netflix's case, the expansion of its content has the added benefit of increasing the consumer surplus its subscribers experience, which creates opportunities for future price increases.

Overhead

In addition to the amortization costs on content assets, Netflix, like other companies, has costs related to Sales and marketing, Technology and development, and General and administrative. The development of these overhead costs is briefly explained below.

The percentage of Sales and marketing relative to Netflix's revenue has decreased from 13% in 2019 to 7% in the past fiscal year. Despite an increase in absolute terms ($2.7 billion in 2019 to $2.9 billion in 2024), this overhead category also demonstrates Netflix's economies of scale, as the percentage declines while revenue grows at a faster rate.

Technology and Development costs are primarily related to employee salaries in these departments, as well as expenses for Netflix's proprietary software and hardware. These costs have increased at roughly the same pace as Netflix's revenue (8% of revenue in both 2019 and 2024).

A decrease is visible in General and administrative costs, from 5% in 2019 to 4% in 2024.

Operating Income

Netflix's revenue has grown at a faster rate than the costs required to generate that revenue. Both the cost of revenue and most overhead costs have increased at a slower pace than Netflix's revenue. This has resulted in a significant increase in operating profit.

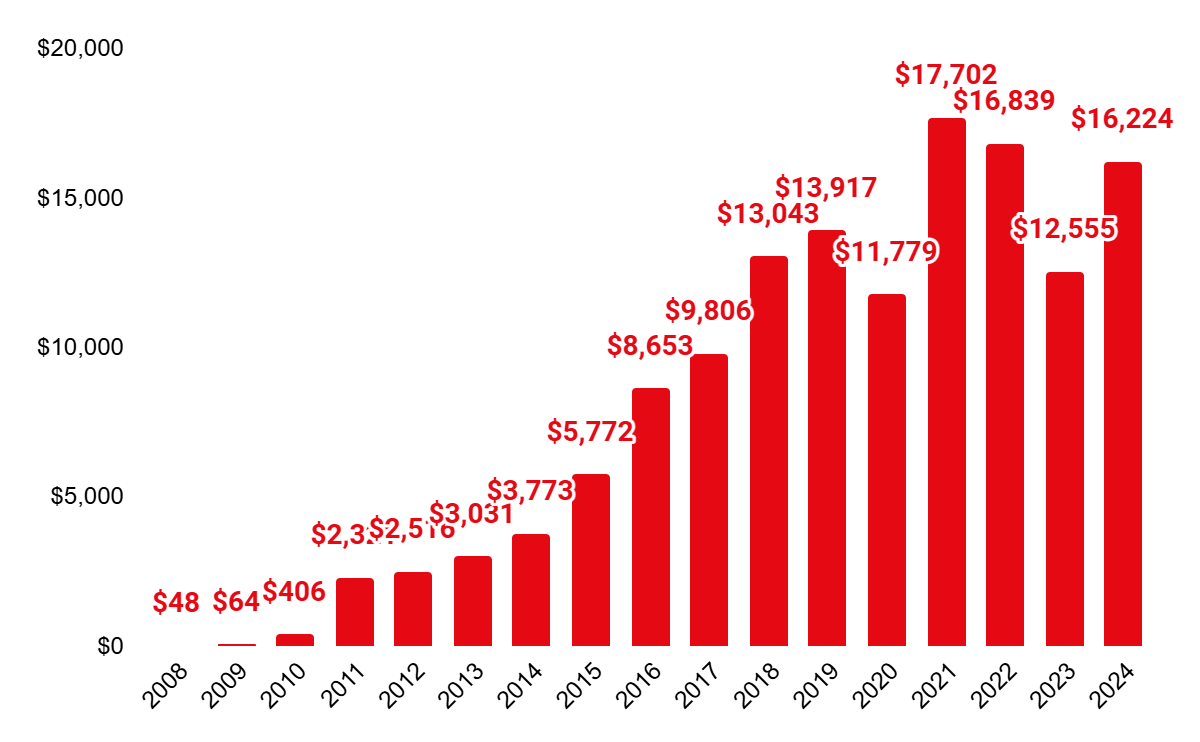

As early as 2003, Netflix was operationally profitable (EBIT), reporting an operating profit of $4 million on $270 million in revenue (its net profit was also positive for the first time that year). Since then, Netflix's revenue has grown to $39 billion in the last fiscal year, with an operating profit of $10.4 billion. The chart below shows the evolution of Netflix's revenue and operating profit since 2012 (in dark red and light red, respectively), including the operating profit margin (as a percentage of Netflix's revenue) in black.

The chart clearly shows the strong increase in Netflix's operating profit margin. With its transition to streaming, the company had to make substantial investments for its size, effectively rebuilding its operating margins after a period of 7% to 13% margins from 2006-2011.

Looking at the annual reports from 2009 onwards, we can see that Netflix invested heavily in its streaming content library (2009: $64 million; 2010: $406 million; 2011: $2.3 billion; 2012: $2.5 billion; 2013: $3 billion; 2014: $3.7 billion). The amortization of these investments followed with a slight delay, as content is amortized over a period of approximately four years.

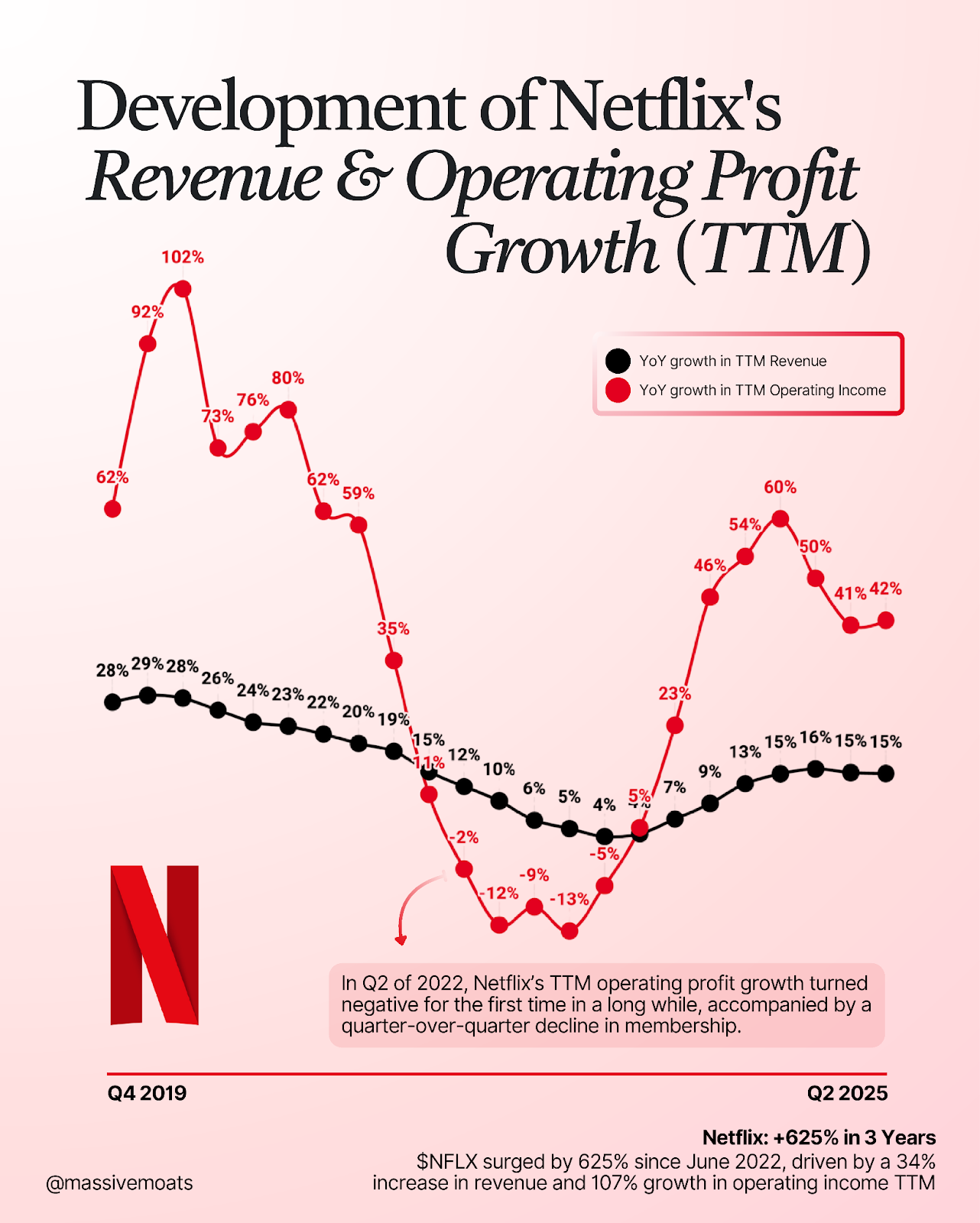

The visual below shows the year-over-year growth of Netflix's revenue and operating profit since 2019.

Although Netflix's TTM year-over-year revenue growth has never been negative during this period, the company's operating profit saw negative growth in the 2022-2023 period. Because the company had significantly increased its content investments in the preceding years ($17.7 billion in 2021 and $16.9 billion in 2022, compared to $11.8 billion in 2020), the cost of its revenue rose, not just in absolute terms but also as a percentage of revenue, which saw only minimal growth during that time. As a result, Netflix's operating profit showed a year-over-year contraction in the 2022-2023 period. This occurred while the company continued to invest in its future, despite a temporary slowdown in revenue growth.

Over recent years, Netflix's Additions to content assets have increased to $16.9 billion in 2022, $12.6 billion in 2023, and $16.2 billion in 2024, as seen in Netflix's cash flow statements for these fiscal years. In absolute terms, this is a multiple of what Netflix spent in the early years of streaming.

Thanks to the growing subscriber base, the amortization costs are more than offset now: the amortization costs per subscriber are declining. This has resulted in a sharply increasing operating profit margin for Netflix over the past two years.

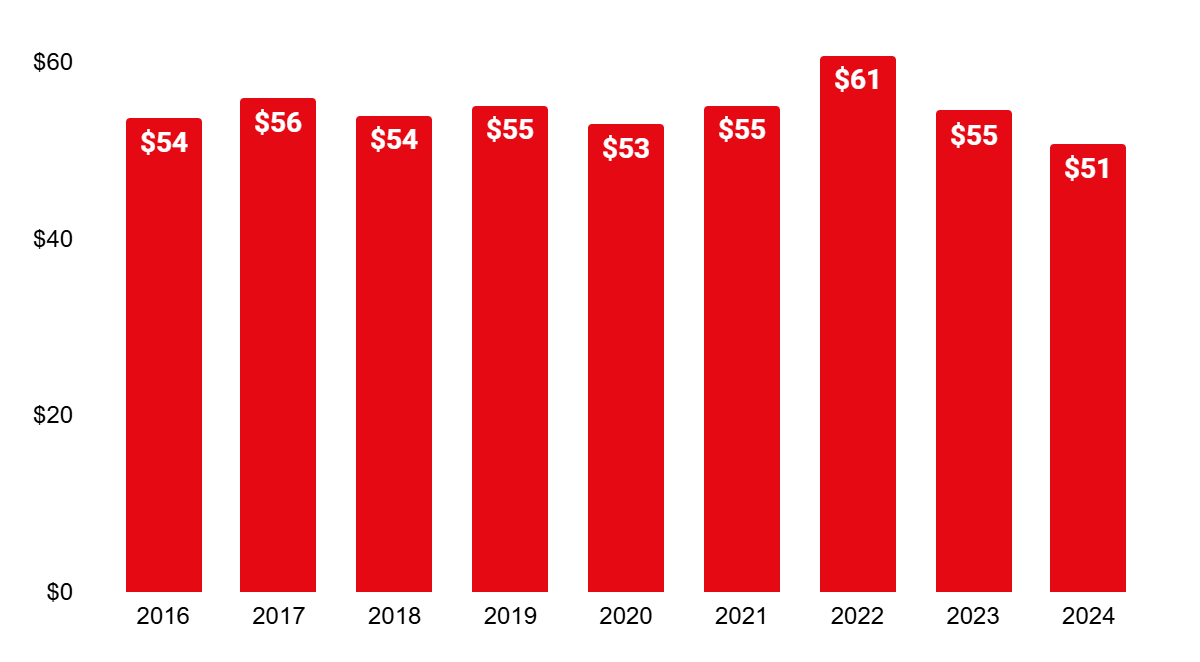

The increase in amortization costs per subscriber [Amortization of content assets / Paid memberships at end of period] around the 2022 period is also visible in the chart below, where the average annual amortization cost per subscriber rose to $61.

Since then, this key metric has been on a downward trend: from $61 that year to $51 in the last fiscal year. In other words, Netflix's amortization costs per subscriber are decreasing. With revenue of approximately $140 per year per subscriber over the last 3 fiscal years, and overhead costs that are either declining or growing in line with revenue, more is left for the company's operating profit.

Net Profit

The gap between Netflix's EBIT and net profit is accounted for by interest income and expenses, as well as taxes. Over the past three fiscal years, Netflix achieved a net profit of $4.5 billion (2022), $5.4 billion (2023), and $8.7 billion (2024).

Earnings Per Share (EPS)

Through share repurchase programs, Netflix has been able to slightly reduce its number of shares outstanding. While it had an average of 451.3 million diluted shares outstanding in 2022, this figure was an average of 439.3 million diluted shares in 2024.

It's important to note that Netflix provides a portion of its employee compensation in the form of share-based compensation, which has a dilutive effect on the number of the company's shares outstanding. More on this in the next section.

Netflix's EPS doubled over the past two years, from $9.95 in 2022 to $19.83 in 2024, after having already more than doubled since 2019 ($4.13) (diluted EPS).

That concludes the analysis of Netflix's income statement. Let's move on to the statement of cash flows.

4.4 | Statement of Cash Flows

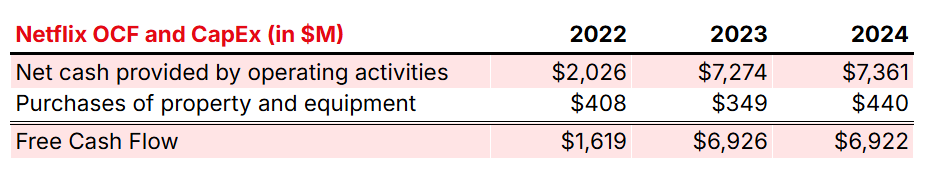

The image below shows Netflix's operational cash flow for the last three fiscal years.

As previously mentioned, the additions Netflix makes to its content assets are visible (Additions to content assets), as is the amortization of these assets (Amortization of content assets). Since the amortization of these content assets is included in the cost of Netflix’s revenue, you won't find it under investing activities in the statement of cash flows.

Additionally, there are regular changes in non-cash items and working capital.

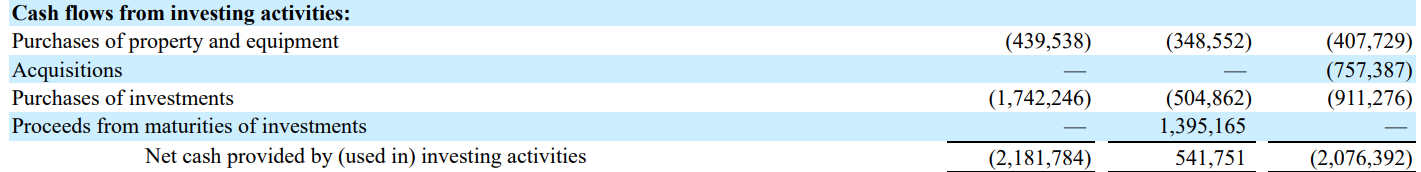

Capital Expenditures

The table above outlines Netflix's investing activities from its statement of cash flows. Since Netflix includes the investments and amortization of its content assets in its operating cash flow statement, the investments listed under investing cash flow primarily relate to the purchase of Property and equipment and the Purchase of investments (i.e., short-term investments). The Acquisitions from 2022 relate to the purchases of Next Games (Netflix, 2022), Boss Fight Entertainment (Netflix, 2022), Spry Fox (Netflix, 2022), and Animal Logic (Netflix, 2022). In 2021, the company made acquisitions totaling $788 million, namely The Roald Dahl Story Company (Netflix, 2021), Scanline VFX (Netflix, 2021), and Night School Studio (Netflix, 2021). In the more recent years of 2023 and 2024, the company made no acquisitions.

Below is a representation of Netflix's free cash flow over the last three years.

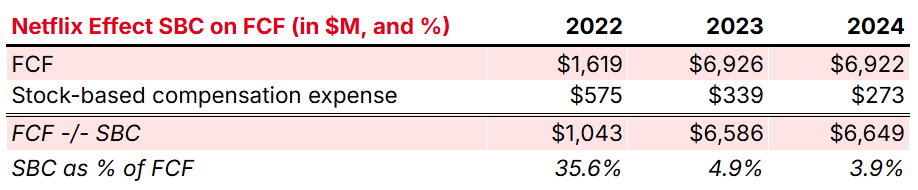

Stock-based compensation

In addition to regular adjustments to Netflix's non-cash items, the Stock-based compensation expense (SBC) line item is also visible. Below, these SBC costs are expressed as a percentage of the company's free cash flow (FCF).

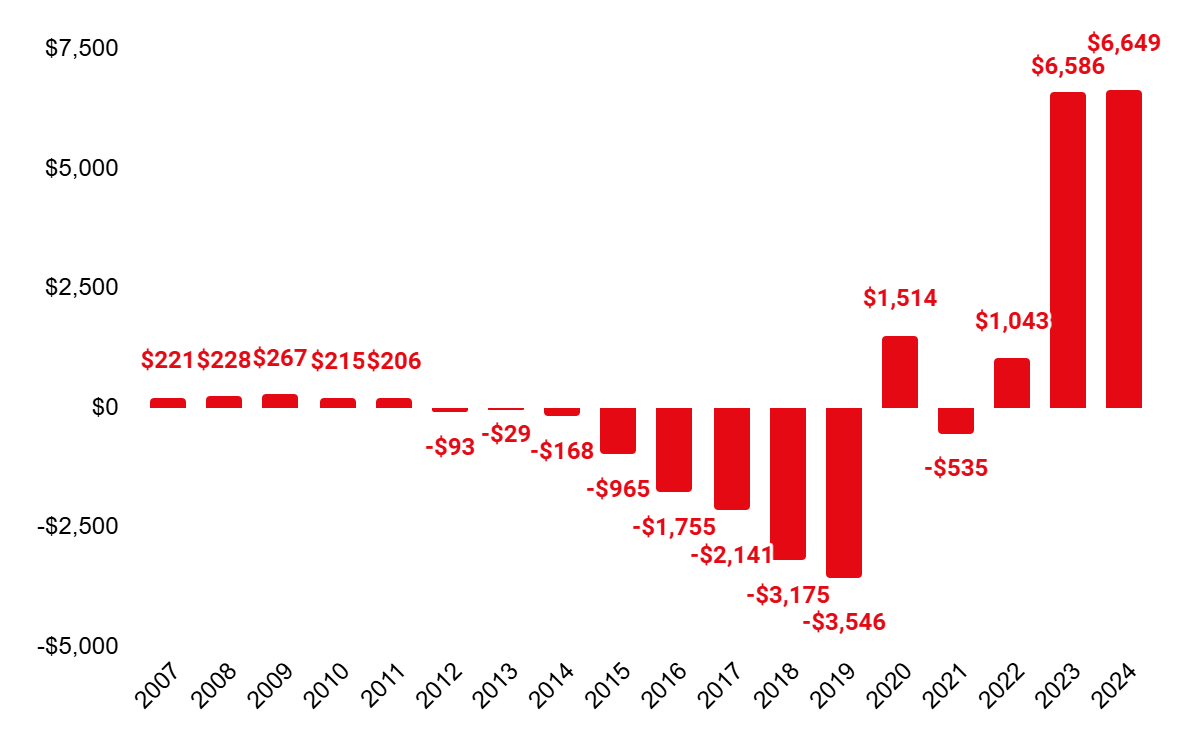

A positive trend is visible for SBC as a percentage of Netflix's FCF. The chart below shows Netflix's FCF minus SBC since 2007.

This chart also indirectly reflects Netflix's large capital expenditures over the past few decades, particularly from 2015 through 2019, when the company was heavily investing in its future.

These investments have paid off. Thanks to its early and substantial investments in streaming, Netflix has secured a leading role in this market. Despite this success, it continues to invest heavily in expanding its content assets. In my opinion, this is necessary to maintain its current position and potentially strengthen it in the future.

Netflix's past investments have led to a significant increase in its free cash flow over the last five years (a cumulative $15.3 billion including the SBC correction; $17.3 billion excluding the SBC correction). After reaching a low of approximately negative $3.5 billion in 2019, Netflix's FCF improved year-over-year by $5.1 billion to a positive $1.5 billion in 2020, and after a temporary dip in 2021, it resumed its upward trend to approximately $6.6 billion per year over the last two fiscal years.

What to do with all this money?

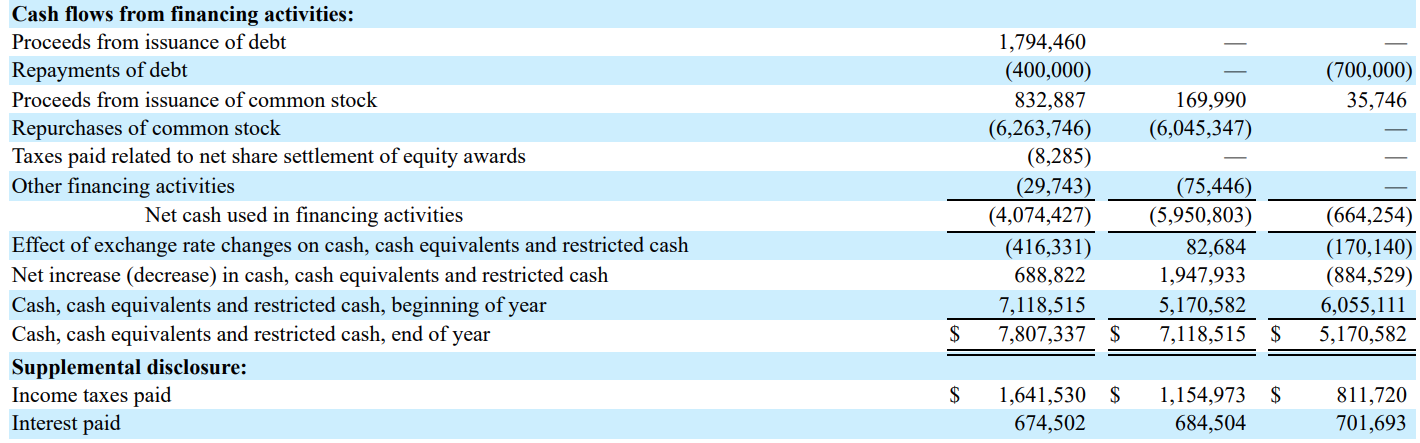

4.5 | Capital Allocation

Netflix aims to maintain a cash balance of about two months' worth of revenue. Any excess cash is returned to shareholders over time (Netflix, 2023).

A company can return capital to its shareholders in two ways: by paying dividends or by repurchasing shares on the open market. When these repurchased shares are subsequently retired, the EPS and FCF per share increase, and as a result, the intrinsic value per share rises.

Dividends

Netflix has never paid a dividend in its history. In its most recent annual report, the company stated that it does not plan to do so in the near future (Netflix, 2024).

Share Buybacks

Since 2021, Netflix has allocated its excess cash to share repurchase programs. These share buybacks (SBBs) are initiated when Netflix's cash balance allows. The company does not try to time the market but views its buybacks more as a price averaging strategy.

We don't try to time the kind of stock price. So we really are caught in more in a, call it, more of a price averaging sort of approach and that we buy back over time as we have excess cash.

— CFO Spencer Adam Neumann (2024)

Netflix first repurchased its own shares in 2021, with a figure of $600 million listed in its cash flow statement for that year.

In 2023, Netflix bought back over $6 billion of its own shares. In 2024, it repurchased over 9.8 million shares on the market, totaling $6.3 billion (Netflix, 2024).

In September 2023, the Board of Directors approved a $10 billion share repurchase program. In December 2024, an additional $15 billion was authorized. As of December 31, 2024, the company had a remaining authorization of $17.1 billion for share buybacks under its current programs.

My View on (Netflix's) Capital Allocation

First and foremost, a company's management has the primary responsibility of exploring opportunities to generate optimal returns on the company's operating free cash flows. If no value-creating investment opportunities (ROI > WACC) are foreseen in the short to medium term, and the company's balance sheet is already optimally structured, management can then proceed with returning this excess cash to shareholders in the form of dividends or by repurchasing shares on the open market.

With Netflix's management approach to capital allocation—using excess cash for share buybacks via a price averaging strategy—the development of intrinsic value per share is partly dependent on the stock's market price.

If we assume that long-term shareholders' returns align with the growth in intrinsic value per share, this growth will be slightly greater if Netflix's stock price happens to be lower at the time of buybacks, and lower if the price is higher. This is because at a relatively high stock price, Netflix can repurchase fewer shares, while at a relatively low price, it can buy back more shares for the same amount of money.

If we define the role of management as optimizing the long-term growth of intrinsic value per share, then one could argue that management should have an idea of where the company's actual intrinsic value stands relative to its market price.

To optimize shareholder returns, I believe that management must have a view on its own stock price when it comes to allocating earned capital.

A potential drawback of this approach is that if management takes this approach, they might not repurchase shares for an extended period if the stock's market price remains above the company's implied intrinsic value for a long time. In that scenario, a DCA strategy might have actually yielded a higher return for the company's long-term shareholders.

In my opinion, paying dividends is a better method of capital allocation during times when the stock price is above the implied intrinsic value per share. By returning capital through dividends, you give shareholders the choice to buy additional shares themselves if they have a different view on the valuation at that time.

Chapter 5 | Culture & Management

As of December 31, 2024, Netflix had approximately 14,000 full-time employees (Netflix, 2024), with about 9,600 in the United States and Canada, and 2,200 in EMEA.

The best work of our lives

At Netflix, we aspire to entertain the world, thrilling audiences everywhere. To do that, we’ve developed an unusual company culture focused on excellence, and creating an environment where talented people can thrive—lifting ourselves, each other and our audiences higher and higher. (Netflix, 2025)

Culture

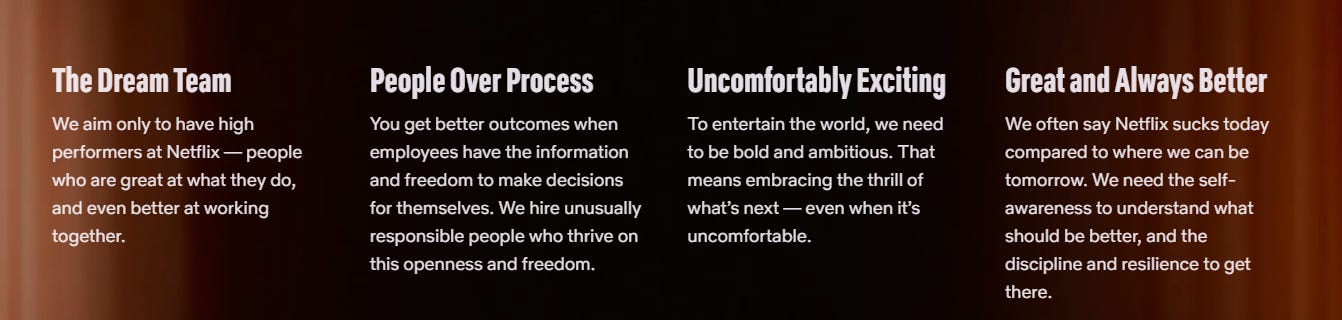

Netflix's culture is based on four core principles: The Dream Team, People Over Process, Uncomfortably Exciting, and Great and Always Better.

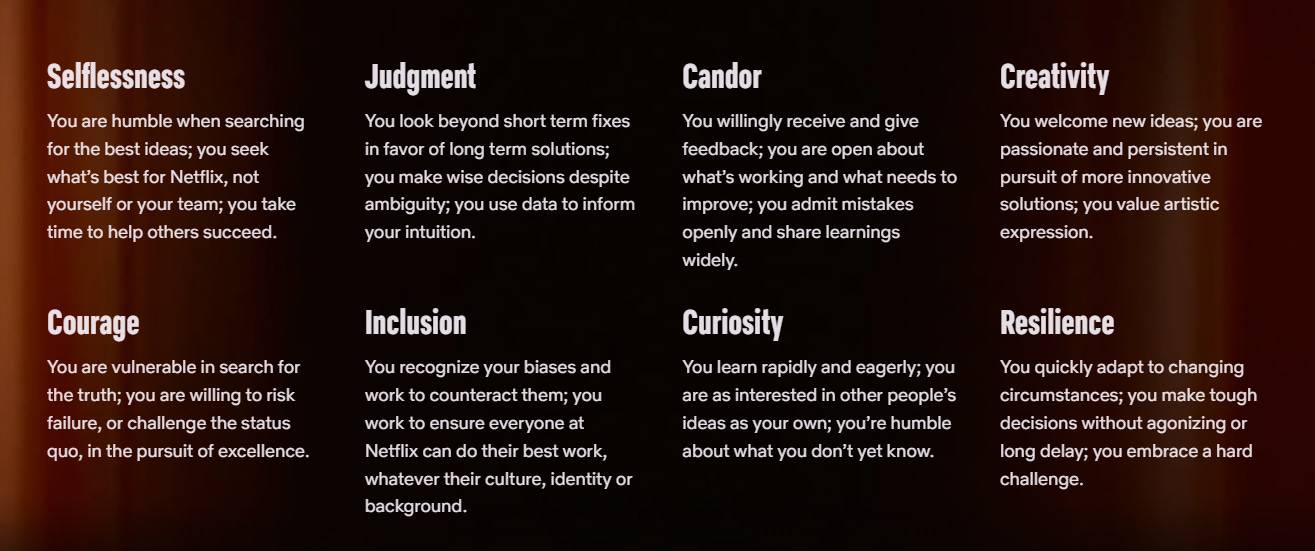

Based on these core principles, Netflix has specifically highlighted eight values that members of its Dream Team should possess.

I find Candor and Courage particularly strong. These values repeatedly come up when you delve into Netflix's history. Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings shared a similar "radical honesty" with each other. This requires both open-heartedness and courage—a powerful combination for moving forward efficiently and quickly.

As such, Netflix's culture has been truly shaped by the values of its founders, reflecting who they were and what they did in the company's early days, as Marc Randolph (2019) beautifully describes in his book. He emphasizes that culture isn't just nice words on a website or the stories you tell; it's who you are and what you do. This is a central theme in the 125-page PowerPoint presentation on Netflix's culture that Reed Hastings shared with employees in August 2009, which has since been made available externally as a showcase for Netflix Jobs in order to target the right candidates (Netflix, 2024).

In the lead-up to what Netflix would become, employees of its early days were paid less than at other companies. This was because the initial capital of $2 million, available at the end of 1997, had to be invested primarily in creating a website and building a DVD inventory.

Essentially, the earliest employees had to accept significantly lower compensation than they were used to from previous employers at the time. Nevertheless, employees were given exposure to Netflix's future success through stock options. This created an extra extrinsic motivation to contribute to the company's success.

Intrinsic motivation came from a shared mission, along with a great deal of freedom and responsibility. Netflix would later codify this as "Freedom and Responsibility."

Netflix later became known as an employer with above-market-rate salaries (S&P Global, 2021), a policy the company itself describes as "Pay Top of Market." In return, Netflix expects high performance. The company views its employees not as family, with unconditional love, but as a professional sports team, where only the best players are fielded and underperforming players are let go out of respect for the rest of the team (Netflix, 2025).

This approach was also reflected when Marc Randolph handed over his CEO role to Reed Hastings and later left Netflix entirely in 2002.

Netflix’s Stock Option Program

Netflix employees have the option to allocate a portion of their salary to purchase stock options. These options have a 10-year term, are fully vested upon issuance, and employees retain ownership of them even if they leave the company (Netflix, 2025).

Management

After taking the helm at Netflix in 1999, Hastings led the company as its sole CEO until July 2020. At that time, Ted Sarandos was appointed co-CEO, and he and Hastings led the company together until January 2023. At that point, Hastings' succession was completed with the appointment of Greg Peters as the new co-CEO. Hastings then moved into the role of Executive Chairman, a position often adopted by company founders after their succession is initiated (think of Jeff Bezos at Amazon and Bill Gates at Microsoft) (Netflix, 2023).

Ted Sarandos

Ted Sarandos (born 1964) joined Netflix after meeting Hastings in 1999 and survived the 40% workforce reduction in 2002. Sarandos took charge of Netflix's content operations, leading the company's transition to a greater focus on Netflix Originals. He was appointed co-CEO in July 2020.

Greg Peters

Greg Peters (born 1971) started at Netflix in 2008, where his work included developing global partnerships. He later became Chief Product Officer and Chief Operating Officer, where he focused on product innovations like games and advertising. In January 2023, he took over Reed Hastings' role as co-CEO.

In addition to the co-CEOs mentioned above, Netflix's daily management team includes Spencer Neumann (CFO), who was appointed in 2019 and brings experience from his time at Activision Blizzard and The Walt Disney Company; Bela Bajaria (Chief Content Officer), who joined Netflix in 2016 and is responsible for all Netflix content worldwide; and Eunice Kim (Chief Product Officer), who has been with Netflix since 2021 and has experience in management roles at Google Play and YouTube.

Compensation

Netflix is known for its generous compensation for employees, including its management. However, the generous pay packages for Netflix's executives have drawn criticism from shareholders. For example, in 2023, during the Hollywood writers' strike, shareholders voted against the compensation packages for the newly appointed co-CEOs, with 242 million votes against versus 98 million for (Netflix, 2023).

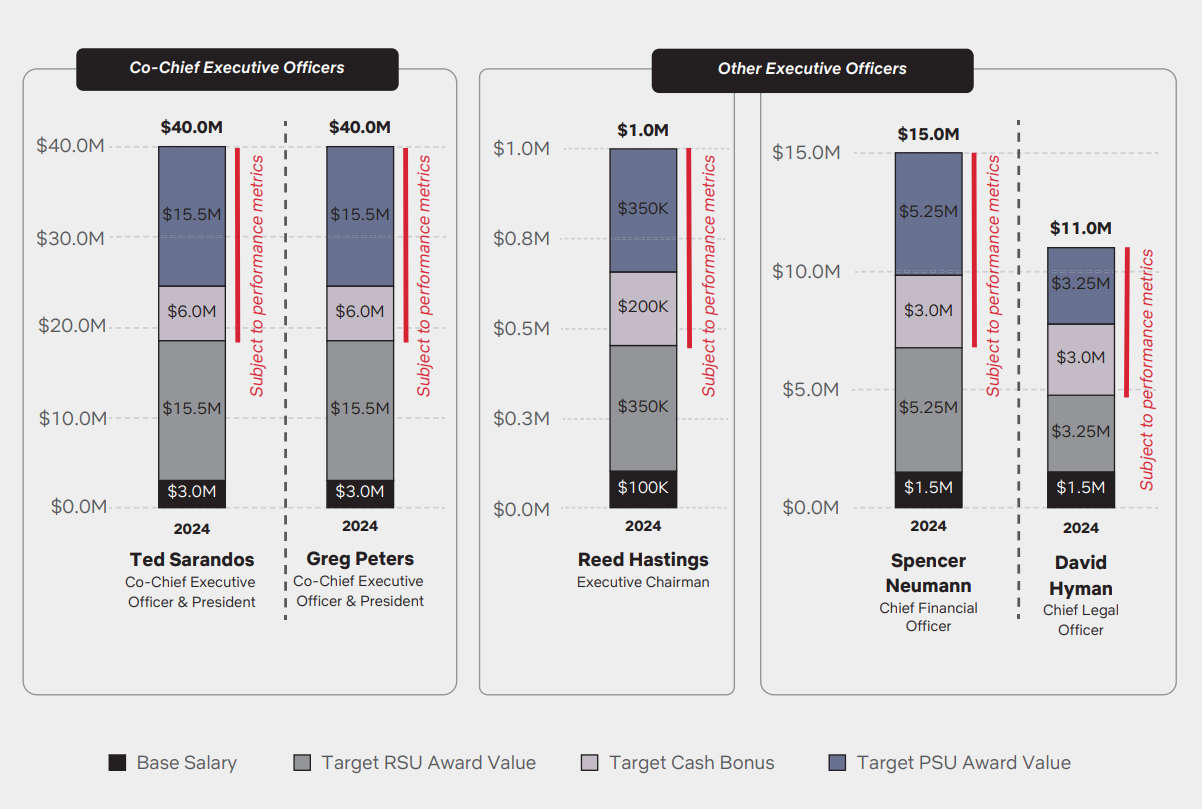

It's worth noting that such shareholder proposals are non-binding. Nevertheless, Netflix has responded. In 2022, after only 26.9% of votes were in favor of executive compensation (Netflix, 2022), the company implemented an annual salary cap of $3 million (Netflix, 2022). The chart below shows Netflix's total compensation for its executive officers in 2024 (Netflix, 2024).

Skin in the Game

As of December 31, 2024, Reed Hastings held 4.2 million Netflix shares, Ted Sarandos held 557 thousand shares, and Greg Peters held 274 thousand shares (all figures include options). On January 24, 2024, Reed Hastings donated 2 million shares to the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, which represented approximately 40% of his holdings at the time (The Wall Street Journal, 2025).

With a large portion of total compensation in equity-related forms through restricted stock units (RSUs) and performance-based restricted stock units (PSUs), as shown in the figure above, there is a sufficient additional extrinsic incentive for strong performance, on top of Sarandos' and Peters' current ownership.

Chapter 6 | Risks & Opportunities

As discussed in the market analysis, Netflix is essentially vying for consumers' leisure time across the entire market. According to the company, its over 300 million subscribers—representing a global reach of more than 700 million people—watch Netflix for an average of two hours per day. A portion of this viewing is done on ad-supported plans.

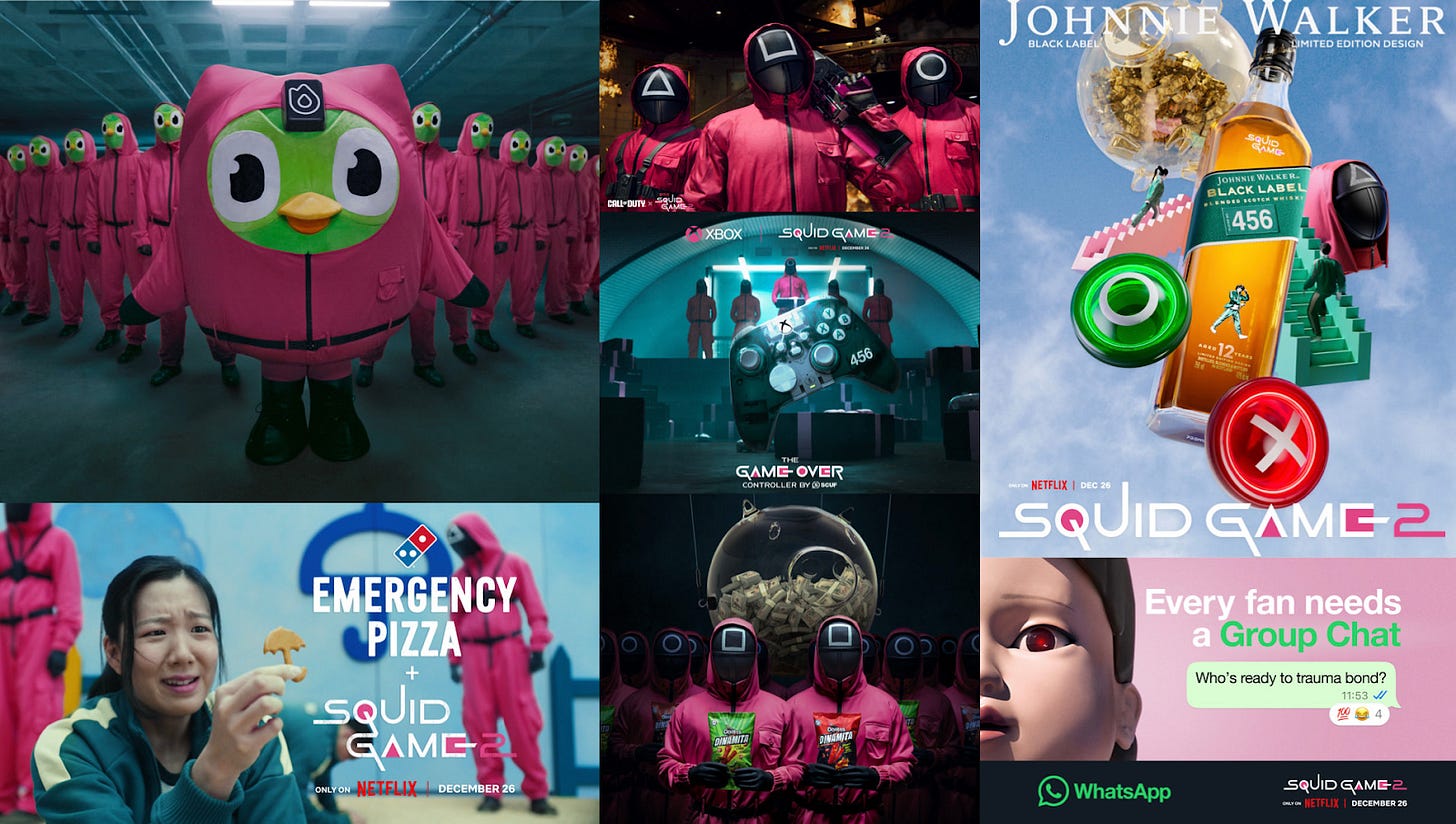

With part of the 95 billion hours of watch time in H1 2025 (+1% YoY), this presents an interesting proposition. Ultimately, the place people most want to spend a portion of their free time in a day is also where, as an advertiser, you want to increase brand awareness, provided it's done correctly. I believe Netflix is handling the adoption of ads on its platform well. For example, the company is working on collaborations to make the ads feel less like traditional commercials, such as by using sets from franchises like Squid Game (YouTube, 2024).

Due to the lower price point for the ad-supported plan, Netflix's ARM has remained flat since 2021. This means that Netflix's subscriber base has shown balanced growth across both the high-end and low-end of its pricing tiers. In my view, Netflix's strategy of keeping the entry-level price of its subscription low in recent years was a good move, as it has encouraged new subscriber adoption.

Streamers

In a scenario of potential intensification of competition among streamers, I expect that consumers will choose a membership with a high-quality, broad content library with ads, over a membership that costs the same but may have a smaller offering in both quality and quantity, albeit without ads. Members who desire an ad-free experience can then upgrade their subscriptions for higher-quality videos without commercials. In this scenario, I believe Netflix would win against other streamers. However, YouTube is a true competitor for consumers' global viewing time.

YouTube's reach is multiple times that of Netflix. This is logical, as the service is free and offers a much larger, user-generated content library. This means YouTube is essentially playing a different game than Netflix, Disney+, HBO Max, and other streaming platforms. The Alphabet subsidiary relies on users continuing to upload content to its platform, including artists and podcast creators—a market that Spotify is also heavily investing in, with deals for its Spotify Originals, among others. In conclusion, YouTube's reliance on creators for continuous content uploads is, in my opinion, both a strength and a certain vulnerability.

This is precisely where streamers like Netflix, Disney+, and HBO Max differentiate themselves with their self-produced content. This is unique intellectual property that you can then commercialize if it is well-received by your audience.